Flat Earthers’ Attempt To Sail To The Edge Of The World Ends In Massive Disappointment

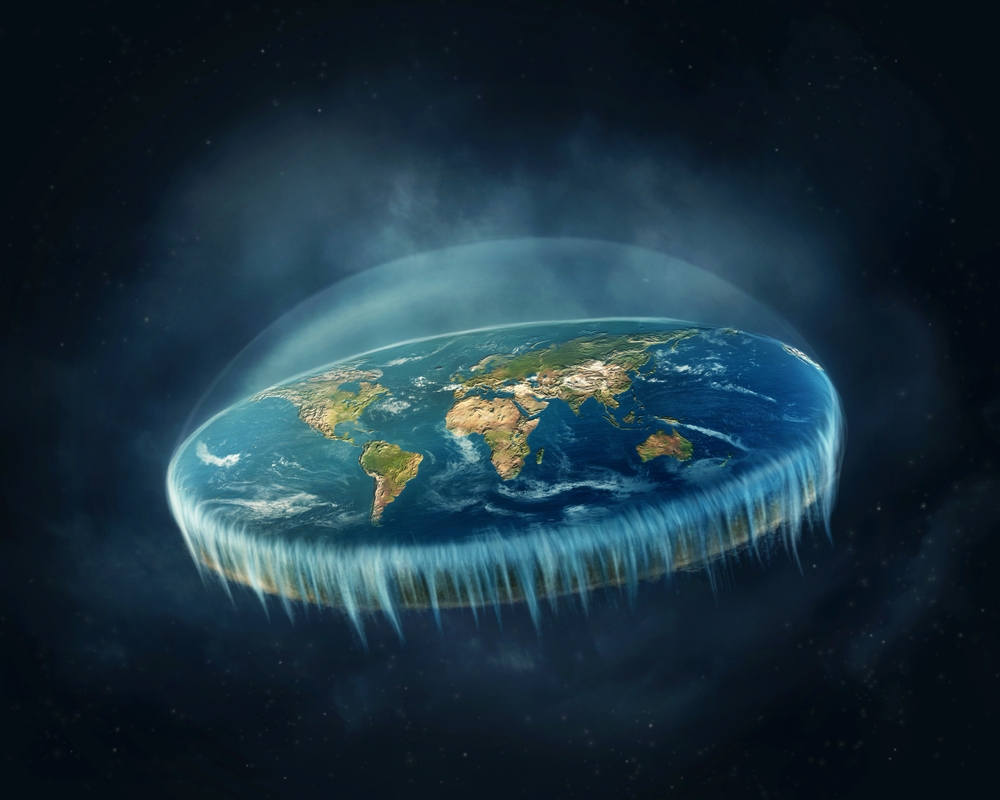

In a world overflowing with satellites, space stations, and instant access to high-resolution images of our planet, the shape of the Earth should no longer be a question. Yet, belief has a strange way of outpacing evidence. In recent years, flat Earth theories have resurfaced, not because of proof, but because of mistrust—mistrust of science, authority, and sometimes even of reality itself. These beliefs might seem harmless at first glance, even laughable. But when acted upon, they can lead people down paths that are both absurd and revealing.

One such story unfolded in Italy at the height of the global pandemic, when two believers set sail from Venice, convinced they could find the world’s edge. To them, the island of Lampedusa was not just another dot in the Mediterranean—it was the literal end of existence. They sold their car, bought a boat, and embarked on a quest that collided spectacularly with reality. Instead of making history, they ended up lost, quarantined, and eventually ferried home, their dream dissolved by the very globe they refused to acknowledge.

The Voyage That Never Reached the Edge

If the Earth were truly flat, proving it would not require elaborate conspiracies or hidden knowledge. It would be as simple as standing at a seashore and watching a ship sail away, its body gradually disappearing below the horizon instead of staying fully visible forever. Or it would take nothing more than a snapshot from astronauts aboard the International Space Station, showing us the supposed flat disc beneath them. Yet despite centuries of science, observation, and evidence available to anyone with a curious mind, not one flat-Earth believer has produced proof that withstands scrutiny. This absence should speak volumes about the validity of the theory, but for some, doubt in scientific consensus becomes fuel for bold, and often misguided, adventures.

That determination came to life in 2020, when a couple from Venice, Italy, decided to challenge centuries of astronomy during one of the most restrictive moments in recent history. Amid the nation’s COVID-19 lockdown, when even stepping outside one’s home was tightly controlled, they made plans to chase the ultimate revelation: to sail to the physical end of the Earth. Convinced that the island of Lampedusa marked the edge of existence, they sold their car, bought a boat, and embarked on what they imagined would be a groundbreaking voyage. In their minds, they were explorers on the cusp of rewriting human knowledge, but in reality, they were setting out on a mission doomed from the start.

Ironically, the very tool they relied on to chart their course—an ordinary compass—undermined their premise from the beginning. A compass only functions because Earth generates a magnetic field, something that is possible only on a spherical, rotating planet. To use such a device in pursuit of a flat Earth was like trying to prove fire doesn’t exist while holding a lit torch. Unsurprisingly, their journey quickly unraveled. Instead of reaching some cosmic cliff or abyss, they wound up lost and exhausted, drifting to the island of Ustica, far from their intended destination. What was imagined as a triumphant unveiling of truth became a cautionary tale of miscalculation.

But the story didn’t end with that first failure. Authorities placed the couple under quarantine for violating lockdown restrictions, yet even that did not extinguish their determination. They attempted to escape again, once more seeking the supposed rim of the world, only to be caught and returned within hours. Their efforts became almost theatrical—a mix of defiance, desperation, and denial colliding with hard reality. In the end, there was no climactic revelation waiting for them, only a ferry ride back to Venice. What began as an attempt to disprove centuries of science ended as a humbling reminder that belief, no matter how passionately held, does not change the shape of the Earth.

The Psychology of Belief in the Impossible

Beliefs shape reality far more than we often admit. When someone is deeply convinced of an idea, even overwhelming evidence to the contrary can bounce off like raindrops on glass. Psychologists call this “motivated reasoning,” where people seek out information that confirms what they already want to believe and reject anything that challenges it. Flat Earth theory thrives in this mental space. To adherents, every scientific explanation, every photograph from space, and every testimony from experts becomes suspect. The absence of proof doesn’t weaken their position—it strengthens their suspicion that a grand cover-up must be at play.

This isn’t simply about one fringe theory. It’s about the human brain’s tendency to cling to certainty when confronted with uncertainty. Conspiracies, in particular, offer something addictive: they make the believer feel like an insider, someone who sees through the lies that billions of others are too blind or complacent to notice. For the Venetian couple who set sail in search of the edge, the journey was more than physical; it was psychological. They were not just moving toward Lampedusa. They were moving toward affirmation of their worldview, a mission to justify the countless hours and emotions invested in an idea that most of society mocked.

The irony is that the more they struggled, the more they may have felt validated. Each obstacle—getting lost, being quarantined, caught again after fleeing—could be reinterpreted not as failure but as proof that they were onto something worth hiding. In this way, belief systems become self-reinforcing fortresses. Facts no longer operate as steppingstones to truth but as enemies that must be twisted or dismissed. The danger of this mindset is that it isolates people from the broader world of knowledge, building walls where bridges should be.

At its heart, this isn’t just about science versus pseudoscience. It is about the vulnerability of the human mind to narratives that grant meaning and identity. To mock the couple is easy, but to understand them is more useful. Their voyage, however misguided, reflects something deeply human: the longing to be right in a world that often feels chaotic, and the hunger to believe in something larger than oneself. That very longing, when misdirected, can lead people not to discovery, but to disillusion.

The Symbolism of Chasing the Edge

Viewed from a distance, the couple’s journey almost feels like an allegory—a parable that could sit alongside ancient myths. Humans have always chased horizons, believing that beyond the mountains, the seas, or the stars lies some hidden truth that will transform our existence. In many ways, this impulse has driven progress. Without it, explorers would never have crossed oceans, scientists would never have split the atom, and astronauts would never have walked on the Moon. But there is a crucial difference between bold exploration grounded in evidence and blind pursuit of a fantasy that defies all logic.

In the couple’s case, their chase for the edge wasn’t the noble pursuit of truth but an attempt to bend reality to their preconceptions. Instead of discovering a new world, they found themselves circling back into the very world they denied. There is something poetic about how their journey ended, not with revelation but with exhaustion, confusion, and a ferry ticket home. In a way, it mirrors the futility of chasing any illusion. The harder one rows toward it, the further away it seems, until the only destination left is disappointment.

Yet there is still something symbolic worth keeping. Their voyage reminds us of the danger of certainty without evidence, but also of the restless spirit that lies in all of us. Every person has their own “edge of the world” they dream of reaching—a goal, a truth, a breakthrough. When guided by humility and reason, this hunger leads to innovation and beauty. When fueled by stubbornness and denial, it spirals into wasted effort and unintended comedy. The lesson isn’t to stop chasing horizons, but to choose the right ones, grounded in reality, not fantasy.

Ultimately, their failed expedition is more than a quirky headline about flat-Earthers. It’s a mirror reflecting back our own tendencies to chase illusions, whether they are impossible ideals, toxic relationships, or false beliefs about ourselves. The edge of the world is not always a geographical place—it is often a mental one. And if we’re not careful, we may find ourselves sailing toward it, convinced of a truth that does not exist, when the greater wisdom would be to set our compass toward horizons that actually exist and enrich life.

The Cost of Denial in a World That Needs Truth

What makes this story more than a curiosity is its timing. The voyage took place during the height of a global pandemic, when misinformation was not just a personal quirk but a public health threat. Millions of lives depended on trust in science, yet distrust and conspiracy theories were spreading as quickly as the virus itself. That a couple would break quarantine laws in pursuit of disproven beliefs speaks to a wider crisis of knowledge and trust in society. The danger is not just in sailing the wrong way but in refusing to acknowledge the consequences of that journey for others.

Denying facts has real-world costs. In this case, health officials had to intervene, resources were wasted, and lockdown rules were undermined—all because of an obsession with disproving something as basic as the shape of our planet. Scale this up, and the same logic fuels movements that deny vaccines, dismiss climate change, or reject election outcomes without evidence. The pattern is the same: clinging to what feels true instead of what is demonstrably true, regardless of the harm it causes.

What’s tragic is that the energy behind these pursuits could be transformative if redirected. The same passion that drove this couple to sell their car and sail into uncertainty could, if pointed toward constructive purposes, fuel innovation, community projects, or scientific endeavors. But denial is an expensive addiction. It consumes time, energy, and resources while producing little more than exhaustion and division. To move forward as individuals and as a society, we must recognize that clinging to falsehoods drains us of the very energy we need to solve real problems.

This is why stories like these are not simply amusing anecdotes. They are cautionary tales about what happens when belief becomes more important than evidence. And in an era where the world faces challenges that demand collective truth—climate change, global health, inequality—this lesson could not be more urgent. The cost of denial is not only personal disappointment but collective vulnerability.

The Power of Curiosity When Guided by Evidence

There is nothing wrong with questioning the world. In fact, curiosity is the root of discovery. Every breakthrough in history began with someone daring to ask, “What if?” But curiosity without discipline can quickly veer into self-deception. The couple who chased the edge of the world were not wrong to wonder—but they were wrong to reject centuries of accumulated knowledge in favor of a narrative that flattered their suspicions. True curiosity does not fear evidence; it embraces it.

This is the paradox of belief: people who think they are rebelling against authority often fall into a deeper form of dependence—on conspiracy theorists, YouTube channels, or fringe communities that reward contrarianism over clarity. But history shows that the most powerful revolutions of thought came from those who were skeptical in the truest sense of the word: open to evidence, willing to be wrong, and committed to following truth wherever it led. Galileo, Darwin, and Einstein were disruptive thinkers not because they ignored evidence, but because they pursued it relentlessly, even when it contradicted their own expectations.

If anything, the story of the flat-Earth sailors can remind us that curiosity is sacred, but it requires guardrails. Evidence is not the enemy of wonder—it is its partner. The telescope did not kill human imagination; it expanded it. The microscope did not shrink our sense of mystery; it deepened it. By rooting curiosity in reality, we don’t diminish the adventure of life—we ensure it leads somewhere meaningful.

When curiosity is guided by truth, it becomes a force for transformation, not self-sabotage. It turns wasted voyages into progress, failed experiments into breakthroughs, and stubborn illusions into opportunities for growth. That is the difference between wandering aimlessly and journeying with purpose.

A Call to Seek Horizons That Matter

In the end, the couple’s journey was not about geography—it was about belief. They did not find the edge of the world because there was none to find. What they uncovered, though unwilling to admit, was something far more telling: the futility of clinging to illusions when reality is all around us, waiting to be embraced. Their story is not one of triumph but of surrender to fantasy, and in that, it serves as a reminder to all of us.

Each of us sails our own seas, guided by the beliefs and assumptions we carry. Some horizons are worth chasing—justice, knowledge, compassion, innovation. Others, like the edge of the world, are mirages that waste our energy and leave us stranded. The question is not whether we will pursue something, but whether we will choose horizons that expand our humanity or ones that shrink it.

To live meaningfully in this world requires more than passion. It requires humility: the courage to accept evidence even when it contradicts our desires, the openness to admit when we are wrong, and the wisdom to align our curiosity with truth. Without that, we risk becoming like the sailors of Venice—restless, determined, but forever chasing a horizon that will never come.

The edge of the world does not exist. But there are edges that do: the edge of ignorance, the edge of injustice, the edge of human potential. These are the frontiers that matter. And if we have the courage to direct our energy toward them, we may not find the end of the Earth, but we will find something far greater—the beginning of a future worth living in.

Loading...