Robert F. Kennedy is Reportedly Pushing to Ban All Sodas & Candy From U.S. Food Stamp Benefits. Thoughts?

A century ago, cigarettes were everywhere sold in corner stores, advertised on billboards, even endorsed by doctors. It took decades of public battles before the U.S. government admitted that tobacco wasn’t just a personal choice but a public health crisis. Today, some argue soda has taken that place in our culture. Sugary drinks are now the single largest source of added sugar in the American diet, fueling an epidemic of obesity and diabetes that costs billions each year in healthcare.

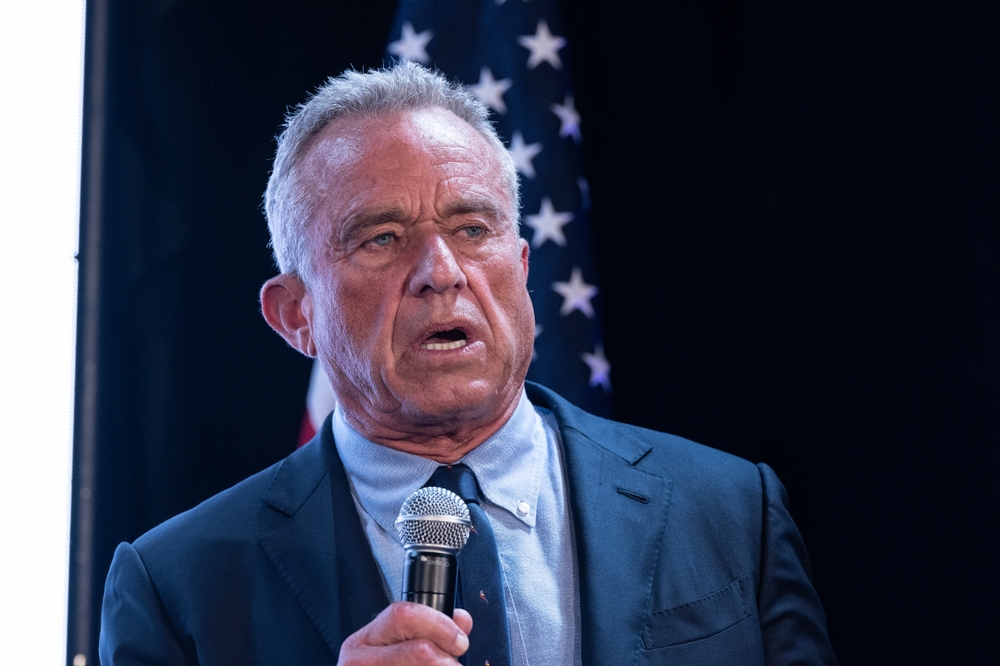

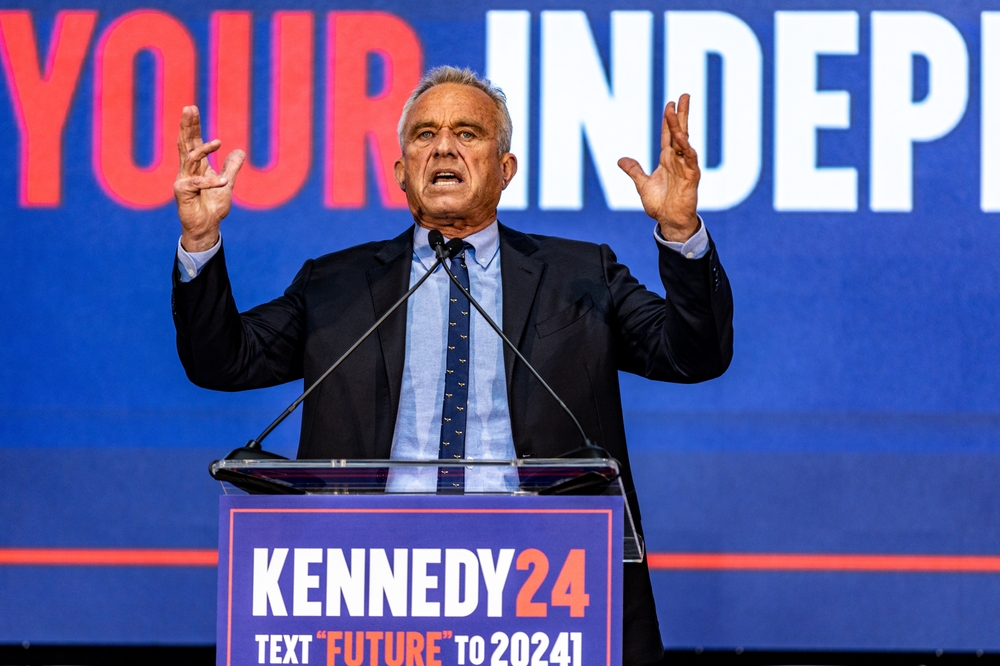

Into this storm steps Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the nation’s Health and Human Services Secretary, with a simple but controversial question: should taxpayer dollars be used to buy soda and candy through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, better known as food stamps? His campaign to “Make America Healthy Again” has ignited a political and cultural clash that stretches from grocery store aisles to the halls of Congress.

What looks like a debate about soda is really a much larger test: how far should government go in shaping what people eat, and where does the line fall between personal freedom and public responsibility?

What Kennedy Is Proposing

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now serving as U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary, has launched a push to reshape what America eats by targeting the nation’s largest food assistance program. At the center of his plan is SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides $113 billion annually to help 42 million low-income Americans buy groceries. Under current law, SNAP dollars can be spent on almost any food or beverage intended for home consumption, with few exceptions alcohol, tobacco, and hot prepared meals are off-limits, but soda and candy have long been allowed.

JUST IN: 🇺🇸 RFK Jr. says he is working to ban all soda and candy from US food stamps. pic.twitter.com/PWOGddJidq

— Remarks (@remarks) April 30, 2025

Kennedy wants that to change. Through his “Make America Healthy Again” campaign, he is urging states to apply for waivers from the Department of Agriculture that would let them ban soda and candy purchases with SNAP benefits. He frames the issue not just as nutrition but as fairness: taxpayers, he argues, are effectively subsidizing products that worsen health and then paying again to cover the medical costs through Medicaid and Medicare. “We are poisoning people with sugars and ultra-processed food,” Kennedy warned, calling soda companies the modern equivalent of Big Tobacco.

Momentum has already begun at the state level. West Virginia, Arkansas, and Utah have announced plans to pursue waivers, with Kennedy personally urging governors across the country to follow. Bills are pending in Congress as well, reflecting growing bipartisan interest. For Kennedy and his allies, removing soda and candy from SNAP is a first step toward reorienting the program around health rather than simply calories, turning food stamps into a tool for disease prevention as much as hunger relief.

The Public Health Argument

Few dispute the science: soda is the leading source of added sugar in the American diet. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than a third of U.S. children are overweight, obese, or prediabetic a trajectory tied closely to sugary drinks. Public health researchers consistently link regular soda consumption with obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses that now account for some of the highest health care costs in the country.

Kennedy has leaned heavily on these numbers. He claims that nearly one in five food stamp dollars roughly 18 percent is spent on candy and sugary beverages, and he has connected that spending directly to rising rates of juvenile diabetes, now affecting almost 40 percent of children. His argument is simple: when taxpayer dollars subsidize these products, society ends up footing the bill twice first at the checkout line, and again through government-funded health care.

That framing has drawn comparisons to tobacco. Just as cigarettes were once marketed as harmless before the evidence caught up, Kennedy warns that sugary drinks are quietly fueling disease in low-income communities already burdened by poor access to healthy food. “We are literally poisoning those neighborhoods,” he said in a recent interview. Supporters argue that allowing SNAP to cover soda undermines the very purpose of the program the “N” in SNAP stands for nutrition and that aligning benefits with health is long overdue.

Nutrition experts generally agree that reducing soda intake would improve health outcomes, but not all are convinced bans are the best path. Dariush Mozaffarian, a leading nutrition scientist at Tufts University, has argued that incentive programs like boosting SNAP dollars when families buy fruits and vegetables may do more to shift diets than outright prohibitions. Still, the underlying consensus is clear: sugary drinks are a public health hazard, and finding ways to curb their consumption could help reduce some of the country’s most preventable diseases.

The Pushback: Autonomy, Equity, and Dignity

Not everyone sees Kennedy’s proposal as progress. Anti-hunger advocates warn that restricting what people can buy with food stamps risks punishing those who already live with the least choice. SNAP provides an average of just $187 per person per month about $6.16 a day. Critics argue that narrowing those options further undermines both autonomy and dignity.

Research also complicates the narrative. Studies show SNAP participants buy soda and snacks at rates similar to other low-income households. In other words, food stamps aren’t uniquely fueling sugar consumption. For groups like the Food Research and Action Center, this raises a red flag: if soda bans don’t meaningfully change health outcomes, they may instead become just another way to stigmatize families in need. “It’s like, how do we restrict people more? How do we stigmatize them more?” said Gina Plata-Nino, one of the group’s leaders.

Personal stories bring this point home. For parents juggling work, bills, and limited food access, small purchases like a soda during pizza night can carry emotional weight. As one mother explained, “The more choice I have, I feel more dignity. I feel more secure in who I am having options which then makes me a better mom and better mental health.” From this perspective, soda is less about sugar than about agency.

There’s also the reality of food deserts. More than 60 percent of SNAP users report that affordability and access to fresh produce are their greatest barriers to healthier eating. In neighborhoods dominated by fast food and convenience stores, removing soda from SNAP doesn’t solve the underlying problem: healthier options often remain out of reach, both geographically and financially. Critics argue that real progress lies in making fruits, vegetables, and proteins more affordable and accessible not in narrowing choices within a program already stretched thin.

Industry Influence and Political Resistance

Any attempt to change what SNAP benefits can buy runs headfirst into a wall of industry power. Sugary drinks are among the most frequently purchased items with food stamps, which means billions of dollars in revenue are at stake for beverage companies. It’s no surprise, then, that the American Beverage Association and its member brands Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and others have mobilized against Kennedy’s proposal. Their message is consistent: restricting purchases stigmatizes low-income families and denies them the same freedom of choice that every other consumer enjoys. “We are fiercely protective of our consumers and their ability to make decisions for their families,” said Meredith Potter, a senior vice president at the association.

The fight has echoes of earlier public health showdowns. Kennedy himself draws comparisons to the tobacco wars, arguing that soda companies are resisting regulation the same way cigarette makers once did, despite clear evidence of harm. But while that framing resonates with health advocates, it collides with a long history of failed restrictions. From New York City’s attempted soda ban under Michael Bloomberg in 2011 to Maine’s waiver request in 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has repeatedly struck down such proposals. Officials have cited the difficulty of defining “unhealthy” foods, the cost of enforcement, and skepticism over whether bans would actually change eating habits.

Politics adds another layer. SNAP falls under the Department of Agriculture, not Health and Human Services, meaning Kennedy cannot directly dictate policy. His strategy has been to rally governors to submit waivers, while Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins signals cautious openness. This interagency tug-of-war creates both momentum and friction: Kennedy brings political firepower, but the USDA ultimately controls the rulebook. And in Washington, where the food and beverage lobby spends millions annually, shifting that rulebook has proven historically difficult.

State-Level Experiments and the Bigger Picture

While Washington debates whether SNAP restrictions are feasible, some states are already testing the waters. West Virginia became the first to ban certain artificial food dyes from school meals and is now pursuing a waiver to block soda from food stamps. Utah quickly followed, with Governor Spencer Cox signing legislation to seek federal approval to cut both candy and soda from SNAP purchases. Arkansas has signaled similar plans. These states are positioning themselves as laboratories for what could become a broader shift in food policy.

What makes this movement noteworthy is its unusual political alignment. Republican-led states have been the early adopters, but Democratic governors like Gavin Newsom in California and Jared Polis in Colorado have expressed openness to considering restrictions. That bipartisan interest reflects a shared concern: rising health care costs tied to diet-related diseases and the role government policy plays in either curbing or fueling them.

If approved, state waivers could serve as test cases. Supporters see this as a way to gather real-world data: Will families buy fewer sugary drinks? Will overall health improve? Can these restrictions be enforced without creating a bureaucratic mess? Advocates hope the answers could guide national reform. Skeptics, however, warn that patchwork bans risk confusing families, straining local agencies, and sidestepping the deeper issue of food access in underserved communities.

A Turning Point for Food, Freedom, and Health

At first glance, the fight over whether SNAP dollars should buy soda or candy looks like a small skirmish in the endless battles over government spending. But look closer, and it becomes something bigger: a test of how America defines responsibility when it comes to food. Kennedy’s campaign highlights a paradox our government is subsidizing products that harm health while simultaneously paying billions to treat the diseases they cause. For health advocates, that’s a cycle we can’t afford to continue.

Yet the pushback matters too. Restricting choices for families already surviving on razor-thin margins risks compounding stigma, especially when healthier food is often out of reach. Critics are right to point out that banning soda doesn’t magically make fresh vegetables affordable or accessible.

What’s really at stake is not just soda but the philosophy behind public nutrition policy. Should food assistance programs prioritize autonomy and dignity above all else, or should they be reoriented to confront the health crises that drain families and public budgets alike? There’s no simple answer, but this debate forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth: food is not just personal fuel, it’s a public issue with consequences that ripple far beyond the dinner table.

Whether Kennedy’s proposal succeeds or fails, it has reignited a national conversation we can no longer avoid. The question is less about soda cans and candy bars than about the kind of food future we want to build for children, for communities, and for a nation straining under the weight of preventable disease.

Loading...