Dandelion Root Shown to Kill Over 90% of Colon Cancer Cells in Less Than Two Days

The internet loves a miracle cure story. Few headlines catch attention faster than the claim that a weed growing between your driveway cracks might one day replace chemotherapy. Researchers testing dandelion root extract reported that it wiped out more than 90% of colon cancer cells within forty‑eight hours in lab conditions. For patients, that statistic is staggering; for scientists, it is an intriguing lead worth following with care. But the road from petri dish to prescription is long and full of obstacles, and this story is as much about the difficulty of medical progress as it is about one plant’s potential.

The dandelion narrative highlights three intertwined truths: that nature often hides powerful bioactive compounds, that turning such compounds into medicine is a slow and expensive process, and that hype can easily outpace evidence.

This isn’t a story about a miracle tea waiting on the supermarket shelf; it is a story about how careful science sometimes stumbles on surprising clues, only to find itself stranded between promise and proof. To understand why people are excited and why doctors are cautious we need to unpack what was really found in the lab, what animal studies showed, why human trials stalled, and what this means for the future of cancer research.

What Happened in the Lab

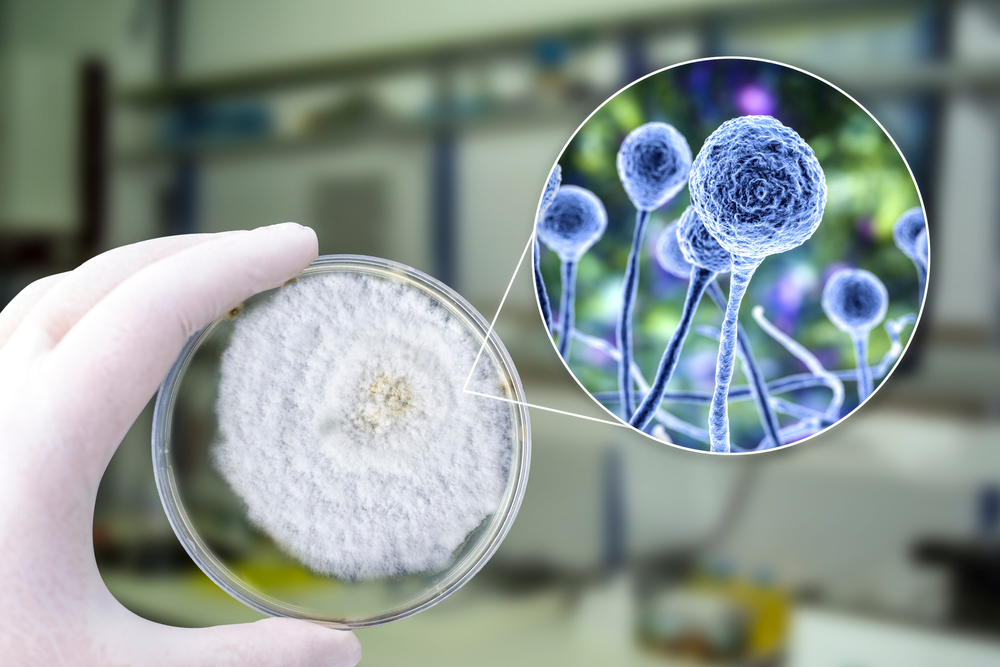

In controlled laboratory studies, researchers exposed aggressive colon cancer cells to an aqueous extract of dandelion root. Within two days, more than 90% of those cancer cells displayed clear signs of programmed cell death, also known as apoptosis. Equally important, normal colon cells treated with the same extract survived unharmed. That kind of selective targeting is rare and highly desirable. Chemotherapy, after all, often kills healthy tissue alongside cancer cells, leading to debilitating side effects.

Scientists dug deeper to uncover how the extract worked. They observed mitochondrial disruption the energy centers of cancer cells destabilized and collapsed. Reactive oxygen species surged inside malignant cells, triggering self‑destruction. Multiple pathways of cell death were activated at once, making it harder for the cancer to resist. The extract’s complexity appeared to be its strength: instead of striking one target, it launched a coordinated assault. Still, scientists cautioned that what works in a dish does not always translate to living organisms. Without the immune system, metabolism, and tissue complexity of a real body, petri dishes tell only part of the story.

What Mice Taught Us

Encouraged by the lab findings, researchers tested the extract on mice implanted with human colon tumors. Unlike injections or isolated compounds, they delivered the dandelion extract orally mimicking how a supplement or drug might be taken by patients. The results were dramatic: tumor growth slowed by more than 90% compared with untreated mice. Even more promising, the mice showed no obvious toxicity. They maintained weight, normal organ function, and activity levels. In cancer research, that combination high effectiveness and apparent safety is a rare find.

Yet mice are not miniature humans. Their metabolism and immune systems differ significantly, and dosing that is safe for rodents may not be safe for people. Tumors in mice grow in simplified environments that lack the full complexity of human cancers. Animal studies are a vital step forward, but they remain stepping stones, not proof. History is filled with treatments that cured cancer in rodents but failed in people. The dandelion story is inspiring, but the gap between mouse and human is wide.

Why the Human Trial Stalled

Dandelion root kills 95% of cancer cells, including:

— ChiefHerbalist (@HerbalistChief) January 23, 2024

🌿Colon cancer

🌿Blood cancer

🌿Pancreatic cancer

🌿Skin cancer

🌿Breast cancer

Make a tea from the roots and take a teacup 2x daily. Apply paste of root on affected part also. Nature heals.

Retweet 🔁 to save a life 🫂 pic.twitter.com/v6J22T8w6y

In 2012, Health Canada approved a Phase I clinical trial of dandelion root extract. Phase I trials are not designed to prove cures their goal is to test basic safety and establish dosage. The trial was aimed at patients with advanced blood cancers, not colon cancer, and recruited those who had exhausted conventional treatments. Unfortunately, the trial struggled with funding and patient recruitment. It eventually stalled before producing any published, peer‑reviewed results. As of today, there is no reliable human data confirming whether dandelion root extract is safe or effective against cancer.

This outcome is common for natural products. Extracts are difficult to patent and standardize, which means pharmaceutical companies see little profit incentive to invest. Public grants and philanthropy often can’t cover the costs of multi‑year trials. Recruitment is another barrier: trials need enough patients who meet strict criteria, and that is harder than it sounds. The lesson here is sobering: science does not always fail because the idea is weak; sometimes it falters because the path forward is too expensive or logistically difficult to walk.

Why Complexity Is Both a Gift and a Problem

Chemical analysis of dandelion root has identified several active compounds, including α‑amyrin, β‑amyrin, lupeol, and taraxasterol. On their own, these molecules show only modest anti‑cancer effects. But together in the extract, they seem to work synergistically, launching a multi‑front attack on cancer cells. This complexity may explain why the whole extract proved more powerful than any isolated part.

For medicine, however, complexity raises difficult questions. How do you ensure each batch of extract is consistent? How do you regulate a product that contains dozens of active chemicals acting in tandem? Pharmaceutical models are built around single active ingredients, making dandelion’s approach awkward for drug pipelines. Without clear standards, regulators cannot approve it, and without patents, companies hesitate to fund it. The very feature that makes dandelion exciting in the lab is what makes it hard to turn into an actual therapy.

What Patients Should Know

For patients and families, stories like this can inspire hope and hope matters. But there are dangers in running ahead of the evidence. Commercial supplements vary wildly in purity and strength; what’s on the label may not match what’s inside. Natural does not mean safe: herbs can interfere with chemotherapy, radiation, or other medications, sometimes reducing their effectiveness or increasing side effects. Most importantly, no supplement should replace proven cancer therapies without a doctor’s guidance.

That said, patients and advocates can play a role in moving the science forward. Supporting organizations that fund early‑stage research helps promising leads survive the gap between lab and clinic. Advocating for smarter clinical trial funding and regulatory flexibility can make it easier for natural products to be tested fairly. And perhaps most importantly, demanding accurate, nuanced reporting can reduce the spread of misinformation that preys on desperate families.

From Weed to What’s Next

The dandelion story is not a miracle cure waiting in your yard, nor is it a meaningless myth. It is a scientific lead compelling, complex, and unfinished. In lab dishes, it decimates colon cancer cells. In mice, it dramatically slows tumor growth without obvious harm. But in humans, the evidence remains absent, stalled by financial and logistical barriers. The responsible path is not to dismiss the finding, nor to hype it as a cure, but to call for the careful, costly, and necessary trials that could tell us the truth.

If science is patient, weeds can sometimes become medicine. For now, dandelions remain what they have always been: hardy plants, overlooked by most, carrying secrets we have only begun to uncover.

Loading...