The Real Difference Between Rare Steak And Rare Chicken

Cutting into a perfectly cooked steak and watching those ruby juices escape feels almost ritualistic. The seared crust, the tender middle, and the burst of savory richness are reasons why steak lovers swear by rare or medium-rare doneness. In fact, the tradition of eating beef lightly cooked is deeply ingrained in food culture across the globe, from the steelworkers of Pittsburgh throwing steaks on smelters to European bistros proudly serving steak tartare. Steak is often celebrated in this form because it balances indulgence with an understanding of how beef responds to heat and bacteria. The rare steak, when handled correctly, is both safe and delicious, giving people the thrill of rawness without the punishment of foodborne illness.

Now flip the plate. Imagine someone serving you chicken with a blush of pink in the middle, juices still tinged red. Instead of delight, you’d probably feel alarm, maybe even disgust. In most cultures, the idea of eating chicken that isn’t thoroughly cooked feels reckless, and for good reason. Unlike beef, chicken carries pathogens that don’t just sit on the surface they can spread throughout the flesh, meaning no amount of clever searing will make that rare chicken breast safe. Yet, curiously, there are places in the world where raw chicken dishes exist, handled with extreme care, but even then, public health experts often discourage the practice. Understanding why one type of undercooked meat is a celebrated delicacy while the other is a minefield of microbes requires looking at biology, history, and culinary tradition all at once.

The Fundamental Difference

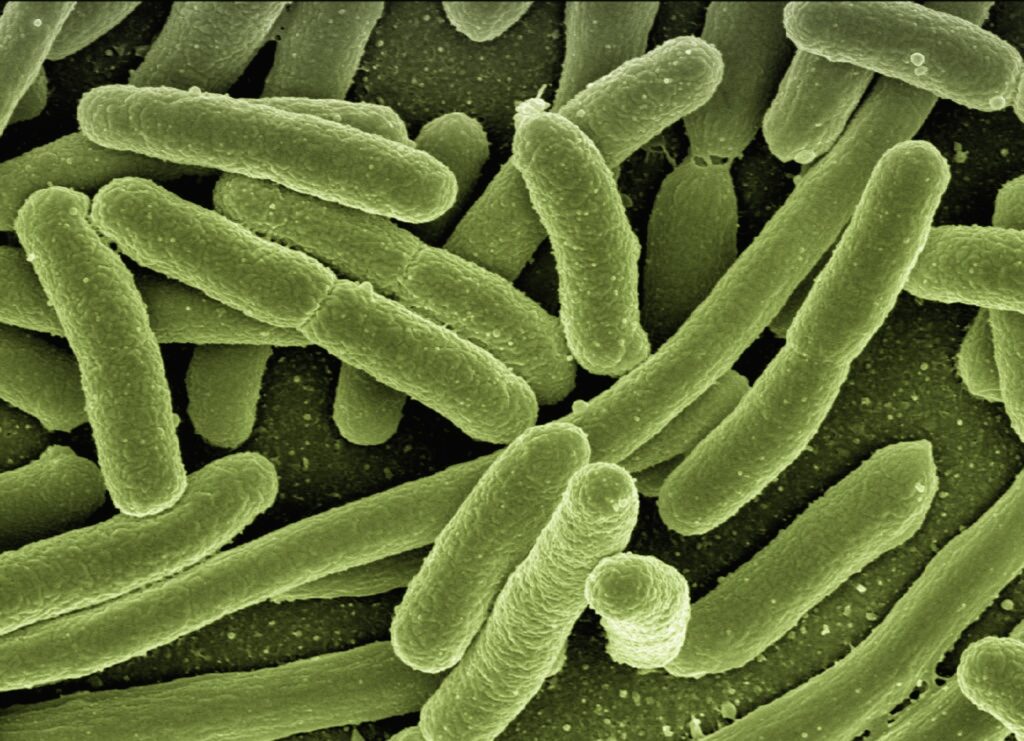

The first key to unraveling the puzzle lies in the way bacteria colonize animals. With cattle, the interior muscle fibers are largely sterile. Harmful bacteria such as pathogenic E. coli usually stay confined to the digestive tract or the outer surfaces. When butchers work carefully, those microbes rarely find their way deep inside a steak. That’s why a high-heat sear is so important: it sterilizes the surface, neutralizing pathogens while leaving the inside tender and rosy. Food-safety experts at the University of Georgia confirm that this principle makes rare steak relatively low-risk when sourced from reputable suppliers. In essence, steak has a natural safety barrier: its own structure.

Chicken tells a different story. Poultry is vulnerable because bacteria such as Salmonella and Campylobacter don’t just linger outside. They permeate the meat itself, traveling through porous fibers and distributing themselves in ways that make a quick sear pointless.

Even if the surface is scorched at screaming-hot temperatures, bacteria may still be alive and well deeper in the flesh. That means the only reliable way to guarantee safety is cooking thoroughly all the way to the center. This biological difference alone explains why people can safely savor rare steak but must treat rare chicken as an edible gamble.

The contrast also explains centuries of culinary habits. Cultures that developed steakhouse traditions were unknowingly aligning themselves with microbiological safety. By contrast, traditions around chicken from roasting to frying emphasize cooking through to the bone because generations of cooks noticed what science later confirmed: undercooked poultry made people sick, sometimes catastrophically.

Rare Steak Vs. Rare Ground Beef

If steak can be enjoyed rare, why does a burger still need to be fully cooked? The answer lies in how meat is processed. With whole cuts like ribeye, pathogens sit on the surface, so searing is enough to make the interior safe. But when beef is ground, that surface along with any bacteria living on it gets mixed into the center. The once-sterile interior is no longer protected. A rare burger might look as alluring as a rare steak, but inside it hides a microbiological wild card. That’s why the USDA and other authorities recommend cooking ground beef to at least 160°F (71°C).

This distinction is not just academic; it shows up in public health data. E. coli outbreaks are far more commonly linked to ground beef than to steak. Restaurants serving steak tartare or carpaccio go to lengths to source meat from butchers who maintain extreme hygiene and short supply chains, reducing exposure to contamination. Burgers, however, often come from industrial-scale processing plants where meat from multiple animals is combined. In such a system, one contaminated cut can affect hundreds of pounds of ground beef, magnifying the risk.

The nuance extends to perception too. For steak enthusiasts, cooking below USDA guidelines is a conscious risk trade-off, with many opting for medium-rare at about 130°F (54°C). With ground beef, however, the trade-off tilts sharply toward risk with little benefit, since the flavors don’t rely on pinkness as much as on fat quality and seasoning. So while the ribeye enjoys cultural acceptance as rare, the burger remains firmly in the “cook it through” camp.

The Curious Case Of Raw Chicken Dishes

Strange as it sounds, there are indeed cultures where raw chicken has a place on the menu. In Japan, torisashi thin slices of chicken sashimi can be found in select yakitori restaurants. Prepared with surgical precision, the meat is typically served with ginger, shiso leaves, or vinegar, intended to highlight delicate textures and flavors. These restaurants source chickens under tightly controlled conditions and handle them with meticulous hygiene. The practice is both rare and controversial, even in its homeland.

Japanese health authorities have grown wary of these dishes. The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare has urged caution, citing repeated foodborne illness outbreaks. Even with careful sourcing, bacteria in chicken are pervasive enough that the risks never truly disappear. Food writers who’ve tasted chicken sashimi often describe it as mild, bordering on bland, which raises a pragmatic question: is it really worth the gamble?

For diners outside Japan, the idea of raw chicken is often unimaginable. In most of the world, pink poultry signals contamination or negligence. Western culinary traditions treat chicken as something that must always reach full doneness, with cookbooks and food authorities warning against the dangers of anything less. These cultural instincts are not paranoia but accumulated wisdom shaped by centuries of people falling sick and learning the hard way.

What The Scary Bugs Do And Who’s Most Vulnerable

When chicken is undercooked, the pathogens it harbors can unleash havoc. Salmonella infections often manifest as fever, stomach cramps, and diarrhea, lasting up to a week. Some drug-resistant strains make recovery even harder. A case from the CDC documented a 10-year-old boy hospitalized after a family vacation, ultimately diagnosed with drug-resistant Salmonella traced back to undercooked chicken. Campylobacter, another common poultry pathogen, causes bloody diarrhea and can sometimes lead to long-term complications like reactive arthritis or Guillain–Barré syndrome, a neurological condition causing temporary paralysis.

These illnesses are not evenly distributed across the population. For young children, elderly adults, pregnant people, and those with compromised immune systems, what would be an unpleasant week of sickness for a healthy adult can quickly spiral into life-threatening territory. Doctors often need to intervene with antibiotics in severe cases, and hospitalization is not uncommon. The seemingly minor risk of undercooked poultry therefore becomes magnified when viewed through the lens of vulnerable populations.

Meanwhile, beef-related pathogens like E. coli generally hit headlines through ground-beef outbreaks, and while dangerous, the pathways of contamination are easier to control through proper cooking and sourcing. This difference reinforces the perception of steak as manageable risk and chicken as reckless hazard. In truth, both require respect, but the balance is far more forgiving with beef.

The Invisible Danger Zone

Even when chicken is destined to be cooked fully, the journey in your kitchen can introduce hazards. Raw chicken juices are notorious carriers of bacteria. A few drops leaking onto a cutting board or countertop can easily contaminate salads, fruits, or bread prepared afterward. This kind of cross-contamination is one of the leading culprits behind foodborne illness.

Food safety experts emphasize practical steps: use separate cutting boards for meat and produce, wash knives and utensils thoroughly between tasks, and sanitize countertops and sinks after handling raw poultry. Handwashing is equally critical twenty seconds with soap and warm water after touching raw chicken can break the chain of transmission. These habits may seem basic, but lapses are surprisingly common, and outbreaks often start with careless handling rather than deliberate consumption of undercooked meat.

Interestingly, beef cross-contamination is also a risk, particularly with ground beef, but the hazards are less insidious than with chicken because intact cuts usually harbor pathogens only on the surface. This means one sloppy cutting board scenario can ruin a whole meal. By respecting these small but crucial practices, home cooks can dramatically reduce their exposure to invisible threats.

How Cooking Temperatures Map To Risk

Cooking is both science and art, and thermometers are the bridge between the two. Guessing doneness by sight or feel may work for texture, but it’s unreliable for food safety. For poultry, the USDA is unequivocal: cook chicken to 165°F (74°C). At that point, both meat and juices run clear, and pathogens are effectively neutralized. Anything less is gambling with bacteria that don’t bluff.

Beef, on the other hand, offers flexibility. The USDA recommends whole cuts reach 145°F (62.8°C) with a rest period, but chefs and steak lovers often push the boundary down to 130°F (54°C) for medium-rare. This comes with a calculated, small risk, but one considered acceptable by many. Ground beef eliminates such wiggle room: its interior is compromised by mixing, and the safety floor rises to 160°F (71°C).

Sous-vide cooking adds another wrinkle. By holding meat at lower temperatures for extended periods, it can pasteurize without drying out. For example, chicken can be safely cooked at 150°F (65°C) for long enough to kill pathogens, then quickly seared for texture. But here, timing is critical, and following precise tables is non-negotiable. The method illustrates how science can expand culinary options, but only when rigorously respected.

Tricks To Make Well-Cooked Chicken

Many people complain that chicken cooked to full safety standards tastes dry and uninspired. Yet culinary techniques can transform it. Brining is one of the most effective tricks: soaking chicken in salted water before cooking helps the muscle fibers retain moisture. Even a quick half-hour brine can mean the difference between juicy and chalky.

Marinating provides another pathway, infusing flavor while also slightly tenderizing the meat. Simple vinaigrettes or yogurt-based marinades can elevate plain chicken breasts into flavorful stars. Breading techniques add crunch while locking in juices, offering the double satisfaction of texture and moisture. And for the adventurous, sous-vide preparation ensures precise doneness, delivering chicken that is both safe and succulent.

The lesson is clear: cooking chicken thoroughly doesn’t mean settling for mediocrity. With thoughtful preparation, fully cooked chicken can be every bit as exciting as steak, offering crispy skins, juicy interiors, and bold flavors. It may lack the romantic blush of rare beef, but it compensates with endless versatility.

Flavor Is Precious; So Is Your Gut

Food connects us to culture, science, and each other. The divide between rare steak and rare chicken is not just about taste but about microbial ecosystems and centuries of human adaptation. The romance of a pink steak and the caution around pink chicken each tell stories of how we’ve learned to balance pleasure with survival.

There is no shame in craving a rare steak, just as there is wisdom in refusing rare chicken. The key lies in understanding the reasons behind these instincts. By combining modern science with cultural memory, we gain the freedom to enjoy food in ways that are both safe and deeply satisfying. Flavor is precious, but so is your gut and with care, you don’t have to sacrifice either.

Loading...