In recent years, science has begun to map what poets and philosophers have long suspected: loneliness doesn’t just hurt the heart it changes the brain. A groundbreaking study published in Neurology has revealed that social isolation is associated with measurable reductions in brain volume, particularly in regions related to memory, emotion, and cognition. The findings come from an extensive analysis of nearly 9,000 older Japanese adults and show that individuals who reported less frequent social contact had significantly smaller brains. While the study cannot claim causation, it provides some of the strongest evidence yet that isolation and reduced social stimulation are linked to neurodegeneration the gradual loss of neurons and brain tissue that characterizes conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

This research builds upon decades of work suggesting that the human brain is a profoundly social organ wired for connection and dependent on it for health. The hippocampus, amygdala, and temporal lobes, all vital to learning, memory, and emotion, appear to atrophy when deprived of meaningful social engagement. The scale of this new study adds statistical weight to what many smaller investigations have hinted at: that loneliness and isolation may be as detrimental to brain health as smoking or physical inactivity. With populations around the world aging and social isolation increasingly described as a public health epidemic, the implications of these findings are profound. The shrinking of the brain is no longer just a metaphor for emotional decline it is a measurable, physical consequence of a disconnected life.

The Anatomy of Isolation

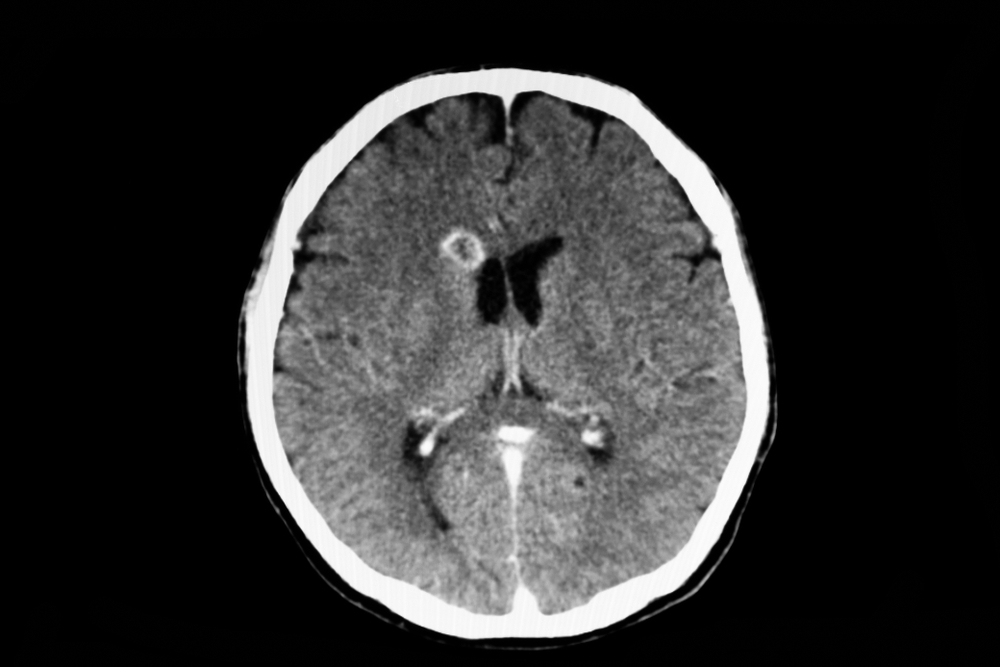

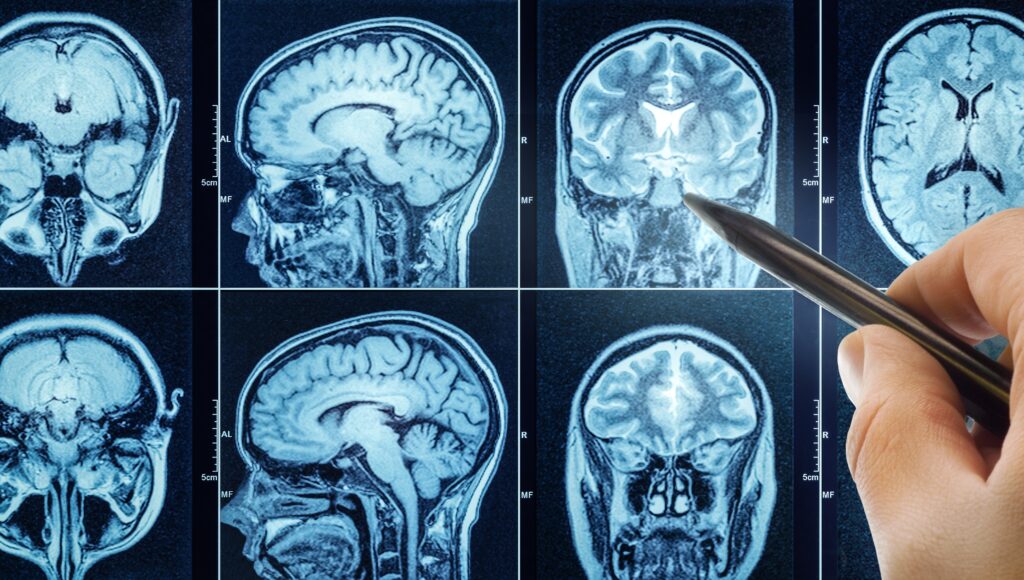

The study, led by Dr. Toshiharu Ninomiya at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan, analyzed brain scans from 8,896 dementia-free individuals aged 65 and older. Participants were asked how often they interacted with people outside their household, whether through phone calls, visits, or shared activities. Their answers were then compared with MRI measurements of total brain volume including both gray and white matter and the presence of white matter lesions, which are small areas of tissue damage often linked to vascular problems and cognitive decline.

The results revealed a striking pattern. Individuals who reported the least social contact had brains that filled just 67.3 percent of their cranial cavity, compared to 67.8 percent among those with the most frequent contact. That 0.5 percent difference might sound negligible, but at the scale of the human brain, it represents millions of neurons.

These losses were concentrated in the hippocampus and amygdala two structures central to memory and emotion processing as well as regions of the temporal and occipital lobes. White matter lesions were also more common in socially isolated individuals (0.30 percent of intracranial volume) compared to those who were socially active (0.26 percent).

Taken together, these data suggest that social isolation affects the integrity of both gray and white matter. Gray matter consists of neuronal cell bodies that handle processing and cognition, while white matter forms the communication highways that link different parts of the brain. Deterioration in either can impair memory, decision-making, and emotional regulation. The association between isolation and white matter lesions is particularly notable, as such lesions have been linked to higher risks of stroke, depression, and dementia. Even when the researchers accounted for other risk factors including age, diabetes, smoking, and physical activity the connection between isolation and reduced brain volume remained robust.

How Isolation Erodes the Brain

Understanding how a lack of social contact translates into measurable brain shrinkage requires exploring the biology of the social brain. One leading explanation is that social interaction acts as a form of cognitive enrichment stimulating neural circuits, encouraging neuroplasticity, and maintaining synaptic connections. The brain, like a muscle, requires use and engagement to remain healthy. When isolated, neural networks associated with communication, empathy, and memory are underutilized, leading to structural and functional decline over time.

A second, complementary mechanism involves stress. Social isolation has been repeatedly associated with elevated levels of cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. Chronic stress triggers inflammation, impairs blood flow, and reduces the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein essential for neuron growth and survival. Animal studies support this connection: mice kept in isolation show decreased hippocampal volume, altered signaling between neurons, and increased inflammatory molecules such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein. These same inflammatory markers have been found in higher concentrations in socially isolated humans, suggesting a shared biological pathway.

Isolation also appears to disrupt neurogenesis the birth of new neurons particularly in the dentate gyrus, a region of the hippocampus critical for learning and memory. Research on humans stationed in remote Antarctic bases for extended periods found that their dentate gyrus volume decreased by nearly 7 percent after 14 months, accompanied by lower blood levels of BDNF. These changes were linked to poorer performance on memory and spatial reasoning tasks. Such evidence indicates that social deprivation is not merely correlated with cognitive decline but may actively impair the brain’s capacity to regenerate and adapt.

The Role of Depression and the Downward Spiral

Depression frequently coexists with social isolation, and in the Kyushu University study, depressive symptoms explained up to 29 percent of the relationship between isolation and brain volume. However, that still leaves more than two-thirds of the effect unaccounted for, implying that isolation has direct neurological impacts beyond mood disorders. Yet the interaction between the two creates a vicious cycle: isolation increases the risk of depression, and depression reduces the motivation to engage socially, which in turn accelerates cognitive decline.

Dr. Howard Fillit of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation describes this feedback loop as a downward spiral of disconnection. As cognitive function deteriorates, people may struggle to maintain conversations, recall faces, or follow social cues, leading to further withdrawal. This self-reinforcing pattern highlights the importance of early intervention not just for mental health, but for the preservation of brain structure itself.

In addition, depression and isolation share physiological roots in the body’s stress response system. Chronic loneliness elevates systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which damage neurons and blood vessels. These effects are compounded in older adults, whose brains are already more vulnerable to vascular injury and reduced neuroplasticity. The result is an environment where even moderate isolation can tip the balance toward cognitive decline.

A Global Perspective on the Isolated Brain

While the Ninomiya study focused on older Japanese adults, its findings resonate globally. Loneliness and social isolation are increasingly recognized as public health crises, particularly among aging populations in industrialized societies. In the United Kingdom, more than half a million people over 60 report spending every day alone, and similar patterns are seen in the United States, where nearly one in four adults over 65 is socially isolated.

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified these trends by enforcing unprecedented levels of physical separation. During lockdowns, researchers such as Daisy Fancourt at University College London tracked tens of thousands of participants to assess the psychological and biological effects of enforced isolation. Their findings confirmed that loneliness and lack of social contact were linked to higher rates of anxiety, depression, and cognitive difficulties. Studies of extreme isolation, from Antarctic expeditions to solitary confinement, further reinforce that prolonged deprivation of social and sensory input alters brain function. People subjected to months of isolation report confusion, emotional instability, and even hallucinations symptoms consistent with disrupted neural communication.

Animal studies provide additional insight into the molecular consequences of isolation. Prolonged separation in rodents increases expression of stress-related neuropeptides such as Tac2 and disrupts normal signaling in the prefrontal cortex, which governs decision-making and social behavior. Blocking the receptor for Tac2 in these animals reduced aggression and improved memory, suggesting that chemical interventions might one day mitigate some effects of chronic isolation. While translating such findings to humans remains speculative, they underscore the fact that the biology of loneliness extends deep into the molecular architecture of the brain.

Isolation, Cognition, and the Brain Reserve Hypothesis

Another framework for understanding these findings is the brain reserve hypothesis the idea that individuals with larger or more complex neural networks can better withstand age-related damage before showing cognitive symptoms. Socially active people, by constantly engaging in conversation, empathy, and problem-solving, may build greater neural reserve throughout their lives. Isolation, by contrast, may erode this reserve, leaving the brain less capable of compensating for natural aging or disease.

Professor Barbara Sahakian of the University of Cambridge notes that social interaction is fundamental to cognitive development, shaping abilities such as empathy, memory, and reasoning. Her research shows that socially isolated individuals not only perform worse on memory and reaction time tests but also exhibit smaller gray matter volumes in many parts of the brain. This suggests that isolation undermines both the structure and function of cognition. Systematic reviews have supported these observations, showing that people with low social participation have up to a 60 percent greater risk of developing dementia.

Importantly, social isolation and loneliness are not identical. Isolation is an objective state the absence of contact—while loneliness is a subjective experience of disconnection. Some people live alone yet feel fulfilled, while others surrounded by people still feel isolated. Both, however, have been linked to negative outcomes for brain health. Studies using the UCLA Loneliness Scale reveal that loneliness correlates with smaller gray matter volumes in the hippocampus and amygdala, mirroring the effects seen with objective isolation. The combination of both conditions appears to pose the highest risk, amplifying stress responses and inflammation.

Protecting the Brain Through Connection

Despite the sobering data, the effects of isolation on the brain may be reversible. Several studies indicate that increasing social engagement can halt or even reverse declines in brain volume. Older adults who join social groups, take part in group hobbies, or maintain regular communication with friends and family show greater cognitive resilience and slower rates of atrophy. Activities that combine social and cognitive stimulation such as learning new skills, volunteering, or attending cultural events appear particularly protective.

Cognitive neuroscience provides a rationale for this recovery. Engaging socially activates broad neural networks spanning the prefrontal cortex, temporal lobes, and limbic system. Each interaction exercises attention, memory, and emotional regulation, essentially serving as mental cross-training. Over time, this stimulation promotes neuroplasticity the brain’s ability to reorganize and form new connections and may increase levels of BDNF, counteracting the degenerative processes of isolation.

Public health experts emphasize that combating social isolation requires systemic change as well as individual effort. Programs that facilitate intergenerational interaction, community centers for seniors, and digital literacy initiatives can all help people stay connected. For those unable to participate physically, video calls and online communities may offer partial substitutes. Although virtual interaction cannot fully replicate face-to-face contact, early evidence suggests it can mitigate feelings of loneliness and preserve some of the cognitive benefits of social engagement.

The Fragile Social Brain

The new evidence from the Kyushu University study reinforces an essential truth about human biology: the brain is not an isolated organ. It thrives on interaction, conversation, and empathy. Deprived of these stimuli, its structures begin to wither not metaphorically, but anatomically. Isolation reduces brain volume, damages white matter, increases inflammation, and accelerates cognitive aging. Depression, stress, and inflammation may all contribute to the process, but they are symptoms of a deeper cause: the loss of meaningful connection.

While the findings do not prove causation, they provide a compelling argument for reimagining social connection as a pillar of neurological health. As modern societies face increasing loneliness, understanding and addressing the biological consequences of isolation may become as vital as tackling obesity or heart disease. The message from neuroscience is unambiguous: connection is nourishment for the brain. To stay mentally sharp and emotionally stable, we must not only exercise and eat well we must also reach out, talk, listen, and belong.

Loading...