Exercise Isn’t Just for the Body, It Can Heal the Brain from Trauma Too

When we think of exercise, we picture sweat, sore muscles, and the grind of physical effort. But what if movement could do far more than build strength or endurance? What if it could rebuild us, not just physically, but emotionally and mentally, helping us let go of pain buried deep within our minds?

Recent research suggests that this isn’t poetic exaggeration. Science is now catching up to what many have intuitively felt for years: our bodies and minds are not separate. They are one ecosystem, and healing one can profoundly affect the other.

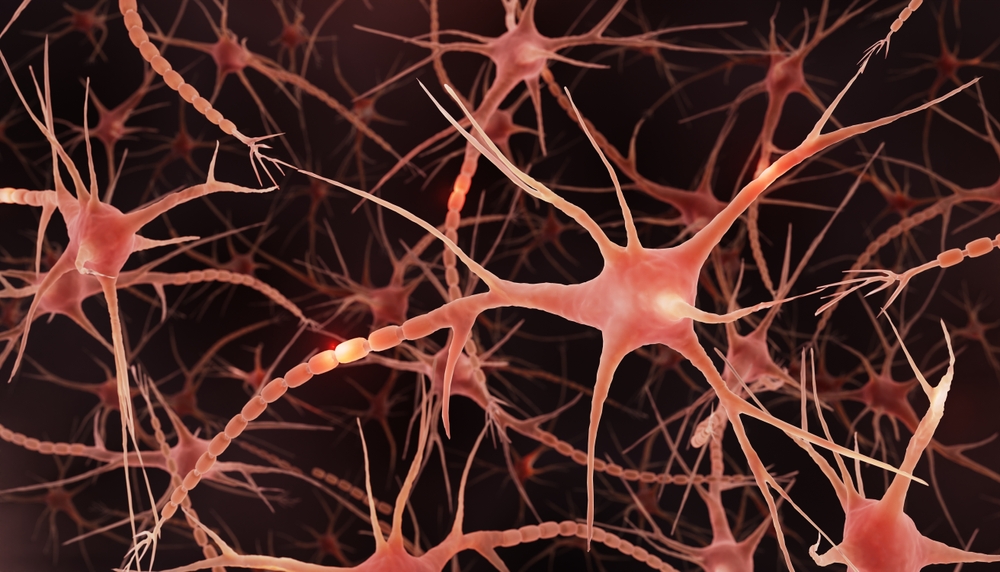

The Science Behind Movement and Memory

A study published in Molecular Psychiatry by the University of Toronto and Kyushu University shows that exercise reshapes the hippocampus, the brain’s memory and emotion hub. By promoting neurogenesis, or the birth of new neurons, movement helps the brain refresh old patterns and create new, healthier ones. Assistant Professor Risako Fujikawa explained, “Neurogenesis is important for forming new memories but also for forgetting memories. We think this happens because when new neurons integrate into neural circuits, new connections are forged and older connections are lost, disrupting the ability to recall memories.”

Her team found that active mice developed stronger neural growth and fewer trauma-related symptoms than inactive ones. Even when genetic methods were used to mimic neurogenesis, the results never matched the benefits of exercise itself. The act of physical movement engaged not only the hippocampus but also improved circulation, hormonal balance, and stress regulation, creating a full-body environment for healing.

When these newly formed neurons rewired the brain, the emotional weight of painful memories began to fade. Mice no longer avoided places tied to fear or drug exposure. Movement literally helped the brain reassign meaning, turning fear into neutrality and compulsion into calm.

This evidence reinforces a powerful truth: the brain is not fixed. Through movement, it continually rebuilds itself, giving us the biological foundation for healing and resilience.

The Hidden Wounds of Trauma

To understand why this discovery matters so much, we must look at what trauma does to the human brain. According to neuroscience research summarized by Everyday Health, emotional trauma isn’t just a “mental” event, it physically reshapes the brain’s architecture.

When faced with threat or stress, the amygdala, the brain’s fear center, goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, the hippocampus, responsible for memory and context, begins to shrink, and the prefrontal cortex, which helps regulate emotions, becomes less effective. As Dr. James Bremner, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University, explained, “[In a healthy person], when you have a trigger, the amygdala is the fear reaction… Then the hippocampus is involved in putting the brakes on the amygdala, as well as the prefrontal cortex.” But in PTSD, he noted, these brakes fail.

The result? A brain that’s constantly on alert, reliving pain, unable to tell the difference between past and present. Dr. Rene Hen, professor of neuroscience at Columbia University, adds that trauma “appears to slow the creation of new cells in the hippocampus.” This might explain why some people stay stuck in cycles of anxiety, depression, or addiction long after the trauma itself has ended.

How Exercise Changes the Story

Here’s where the two stories connect. If trauma reduces the brain’s ability to grow new neurons, essentially freezing it in a defensive state, then exercise may be nature’s antidote. By stimulating neurogenesis, movement reopens the door to mental flexibility, allowing old, fear-based patterns to fade and new, healthier ones to take their place.

In the mouse experiments, exercise not only reduced fear-based avoidance behaviors but also helped the animals forget associations between certain places and traumatic or addictive experiences. Those that once avoided dark compartments, where shocks had occurred, began to explore again. Those that had developed a preference for a room associated with cocaine no longer showed that compulsion after consistent physical activity.

In Fujikawa’s words, “In our experiments, exercise had the most powerful impact on reducing symptoms of PTSD and drug dependence in mice, and clinical studies in humans also show it is effective. I think this is the most important takeaway.”

The implications are profound: trauma may change the brain, but so can healing, especially when we move.

Trauma, Memory, and the Body Mind Connection

Trauma leaves more than emotional marks; it imprints itself on the body’s biology. Each racing heartbeat, tense muscle, and shallow breath can become part of a memory network that keeps the body ready for danger long after the threat has passed. The body becomes the stage on which the past continues to play.

Exercise helps interrupt this cycle. Movement reawakens the communication between the body and the mind, allowing physical sensations to serve as signals of safety rather than of threat. As we move, the body releases stored stress hormones and increases blood flow to the brain. This physiological reset supports the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, regions responsible for emotional balance and context, while calming the overactive amygdala that often governs fear.

From a neurological standpoint, physical activity boosts levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a molecule that nourishes neurons and enhances their ability to form new connections. Regular movement strengthens the parasympathetic system, promoting calmness and focus. This renewed balance allows the brain to reinterpret old cues of fear or sadness and associate them with safety instead.

The process is similar to what trauma-focused therapies like EMDR and somatic approaches achieve through guided awareness, yet exercise offers a self-directed, accessible way to regulate the nervous system. When the body experiences coordinated movement and rhythmic breathing, it reinforces the message that it can inhabit the present moment safely. Gradually, the body’s memory of trauma becomes less dominant, replaced by a lived sense of control and peace.

By engaging both physical and mental systems, movement becomes a language through which healing is expressed. It does not erase what happened but gives the body and mind new ways to coexist with the past. In doing so, exercise turns awareness into recovery and the act of moving into a form of mindful restoration.

Action Steps for Mind Body Healing

The beauty of this research is that it translates into action. Healing is not only found in therapy rooms or laboratories but also in the small, intentional choices we make each day. Below are practical and evidence-based ways to merge movement with mindfulness and emotional renewal.

- Move with intention and awareness. Exercise is most powerful when it is deliberate rather than forced. Begin with simple, sustainable forms of movement such as walking, stretching, or yoga. The goal is consistency, not intensity. Notice how your body feels as you move and allow each motion to be a reminder that you are choosing growth over stagnation.

- Create a routine of rhythm. Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt, strengthens through repetition. Establish a daily rhythm that includes physical activity, even brief sessions of 20 to 30 minutes. Research shows that this regularity enhances both neurogenesis and emotional stability over time.

- Blend movement with mindfulness. While exercising, focus on breath, sensations, and surroundings. Turn your attention to the present moment rather than the inner dialogue of worry or self-criticism. When you synchronize breath with motion, you anchor yourself in now, which helps the nervous system shift away from past trauma and toward calm awareness.

- Include restorative practices. Healing is not achieved through exertion alone. Adequate sleep, stretching, and quiet rest are essential for the brain to consolidate memories and repair neural tissue. Balance effort with stillness, giving both the body and mind time to integrate change.

- Connect with supportive environments. Healing accelerates in community. Joining a group class, nature hike, or movement-based therapy session adds accountability and social connection, both of which enhance brain health. Positive social contact reduces cortisol levels and reinforces a sense of safety.

- Pair physical care with emotional care. Seek professional help when needed. Therapists, trainers, or support groups can tailor approaches to your unique experiences. Professional guidance ensures that exercise complements rather than replaces other evidence-based treatments.

By approaching movement as both medicine and meditation, you engage every part of yourself in the process of recovery. Small, steady actions signal to the brain that safety and renewal are possible. Over time, this practice becomes less about exercise and more about learning to live in harmony with your own body and story.

What This Means for Healing

The takeaway is not that exercise alone can cure PTSD or erase trauma, it’s that movement is a powerful partner in the healing process. Traditional therapies such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure therapy (PE), and EMDR remain vital, but physical activity adds another layer of transformation.

As Dr. Hen emphasizes, early intervention and lifestyle matter deeply. “The earlier you intervene,” he says, “the better your odds of mitigating the possibility that it becomes a chronic condition.” Exercise, mindfulness, and stress management work best not as afterthoughts, but as daily acts of prevention and renewal.

Think of exercise not as punishment for the body, but as a dialogue with it. Every step, stretch, or breath is a conversation, one that says, I am still here. I am healing. I am not my pain.

Featured Image from Pexels

Loading...