Inside The Extraordinary Life Of Maud Lewis And Her Enduring Artistic Legacy

Maud Lewis’s story is one that continues to resonate deeply with Canadians and art lovers around the world. Her paintings appear simple at first glance, filled with bright colors, cheerful animals, and idyllic rural scenes. Yet behind that joyful imagery was a life marked by physical pain, social isolation, and extreme poverty. Lewis did not paint because it was fashionable or profitable. She painted because it was a way to survive emotionally and to communicate beauty when her own circumstances offered very little of it.

Born in rural Nova Scotia in the early twentieth century, Lewis lived during a time when disability was poorly understood and social support systems were minimal. Her life was shaped by hardship from childhood onward, but she never allowed bitterness to define her work. Instead, she created a visual language of optimism that stood in stark contrast to her daily reality. According to All That’s Interesting, her paintings became windows into a world she wished to inhabit rather than the one she endured.

Over time, Maud Lewis became a symbol of perseverance and quiet strength. Her work now hangs in major galleries and museums, yet she spent most of her life unknown and underappreciated. This article explores how Lewis overcame chronic pain, poverty, and marginalization to leave behind one of the most beloved artistic legacies in Canadian history.

A Childhood Shaped By Illness And Isolation

Maud Lewis was born Maud Dowley in 1903 in South Ohio, Nova Scotia. From a young age, she lived with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that severely limited her mobility and caused visible deformities in her hands, shoulders, and spine. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia of Art, her condition made everyday tasks painful and often exhausting, even during childhood. At a time when medical understanding was limited, her illness quickly set her apart from other children.

Lewis spent much of her early life indoors under the care of her parents. She did not attend school regularly and instead received instruction at home. This isolation limited her social development, but it also gave her long, uninterrupted periods to observe her surroundings and explore creative activities. Painting and drawing became both entertainment and comfort, allowing her to express herself without relying on physical strength.

Her mother encouraged her artistic interests and taught her to paint simple holiday cards and decorative items. These early lessons laid the foundation for her later work. The imagery she painted as a child, including flowers, birds, and pastoral scenes, would remain central themes throughout her career. According to CBC Arts, these subjects reflected both nostalgia and a longing for connection to a world that often felt inaccessible to her.

Despite the support she received at home, Maud’s life became increasingly difficult after the death of her parents. Without family protection, she was left vulnerable both financially and socially. This turning point forced her into a new chapter that would test her resilience even further.

Life In Poverty And An Unconventional Marriage

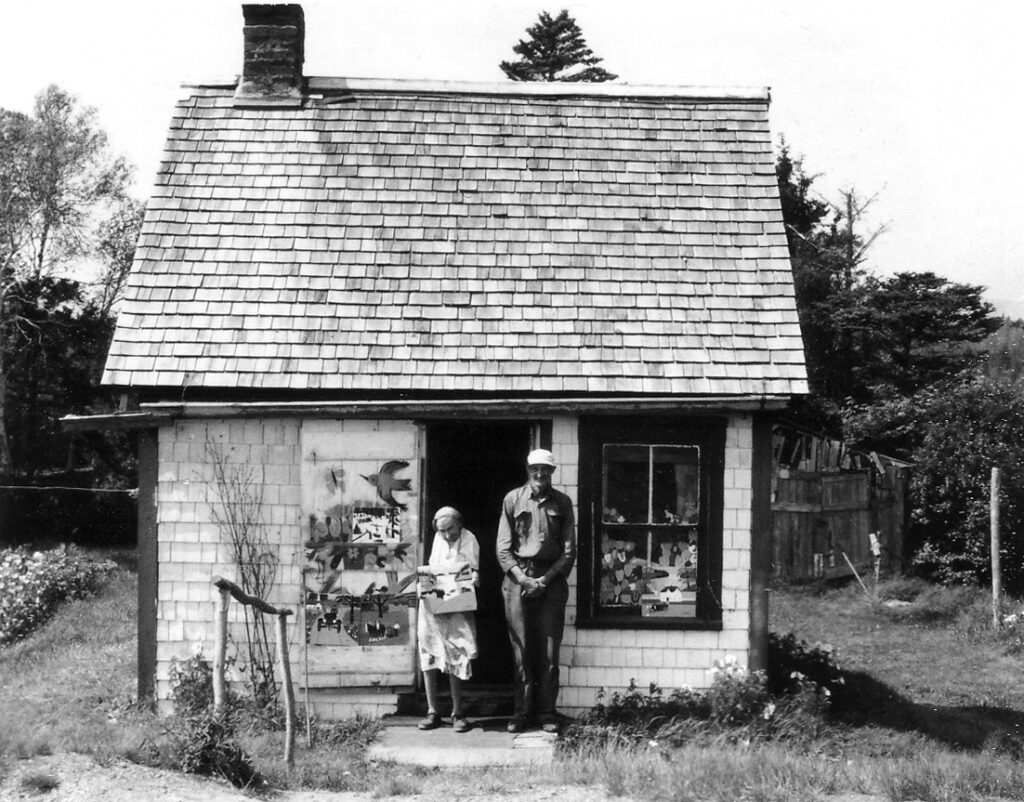

After her parents passed away, Maud moved in with relatives, but the arrangement was short lived. She eventually answered a newspaper advertisement placed by Everett Lewis, a fish peddler looking for a housekeeper. The two later married, and Maud moved into his tiny one room house in Marshalltown, Nova Scotia. According to All That’s Interesting, the home lacked electricity, running water, and adequate heating, which made daily life extremely harsh.

Maud and Everett’s relationship was complicated and often strained. Everett was known to be difficult and controlling, and Maud lived in near total isolation in the small house. The physical demands of maintaining the home, combined with her chronic pain, made daily survival a challenge. Despite these conditions, Maud continued to paint using whatever materials she could afford or acquire.

The couple lived in severe poverty for most of their lives. Maud sold small paintings for just a few dollars, often to tourists who passed by their home. She painted on boards, cardboard, doors, and even the walls of the house itself, transforming the space into a living artwork. According to the Art Canada Institute, this practice blurred the line between art and survival, making her home both a workspace and a gallery.

Though her circumstances were bleak, Maud’s work radiated warmth and joy. Animals pranced across snowy landscapes, flowers bloomed in impossible abundance, and people appeared engaged in simple pleasures. Her art became a form of quiet resistance against despair, offering a version of life shaped by hope rather than hardship.

Developing A Distinct Folk Art Style

Maud Lewis’s artistic style evolved organically, shaped by her physical limitations and lack of formal training. She used simple forms, bold outlines, and flat areas of color that required minimal detail work. According to CBC Arts, her arthritis influenced how she held brushes and applied paint, resulting in a recognizable and consistent aesthetic.

Her paintings often depicted rural Nova Scotia scenes, such as oxen pulling sleds, fishermen at work, and families gathered outdoors. These images reflected both her immediate environment and an idealized vision of community. While she rarely traveled, Maud captured the essence of Maritime life with remarkable clarity and affection.

Unlike many contemporary artists, Maud did not experiment with abstraction or modernist techniques. She remained committed to representational imagery grounded in everyday experience. This sincerity became one of her greatest strengths, allowing viewers to connect emotionally with her work regardless of artistic background.

The Art Canada Institute notes that her work was initially dismissed by some critics as naïve or unsophisticated. Over time, however, scholars and curators recognized the intentionality and emotional depth behind her compositions. Her paintings were not simplistic, but rather distilled expressions of joy, resilience, and memory.

Recognition During And After Her Lifetime

Maud Lewis began to receive wider attention in the final years of her life. A national television feature in the nineteen sixties introduced her to audiences across Canada. According to CBC Arts, this exposure led to increased demand for her work and a modest improvement in her financial situation.

Despite this recognition, Maud’s health continued to decline. Years of arthritis had taken a severe toll, and she struggled to meet the growing demand for paintings. She died in 1970 at the age of sixty seven, leaving behind a body of work that would only grow in significance after her death.

In the decades that followed, Maud Lewis’s reputation expanded dramatically. Her restored home now resides in the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, where visitors can experience the space she transformed through paint. Her works have sold for substantial sums and are considered national treasures.

According to the Art Canada Institute, scholars now place Lewis within a broader discussion of disability art, folk traditions, and outsider art. Her life and work challenge conventional narratives about success, talent, and artistic legitimacy.

Cultural Legacy And Lessons From Maud Lewis Life

Maud Lewis’s story continues to inspire because it speaks to universal themes of perseverance, creativity, and dignity. She did not wait for ideal conditions to create beauty. Instead, she worked within severe limitations and still managed to produce art that resonates across generations.

Her life also invites reflection on how society treats individuals with disabilities and those living in poverty. Lewis lacked access to medical care, financial support, and artistic resources, yet her contributions now define a significant chapter of Canadian cultural history. According to CBC Arts, her story forces Canadians to reconsider whose voices are valued and preserved.

Beyond the art world, Maud Lewis has become a symbol of quiet resilience. Books, films, and exhibitions continue to introduce new audiences to her work and life. Each retelling reinforces the idea that creativity can flourish even in the most difficult circumstances.

Ultimately, Maud Lewis reminds us that joy can be an act of defiance. Through paint, she claimed agency over her narrative and left behind a legacy that continues to brighten lives long after her passing.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Patrick Hatt | Shutterstock

Loading...