Two Atoms Away: How Scientists Stripped LSD of Its Trip and Built a Brain-Healing Drug

Somewhere in a laboratory at the University of California, Davis, a team of researchers made a move so small it almost seems laughable. Two atoms. They shifted two atoms in one of history’s most notorious molecules, and what came out the other side might change how we treat some of the most devastating mental illnesses known to medicine. What happened next is the kind of story that makes you stop mid-scroll and read it twice.

A Drug With a Reputation Problem

LSD has spent decades trapped in a cultural time capsule. Flower children. Bad trips. Government bans. For most people, lysergic acid diethylamide sits firmly in the category of “dangerous drug,” full stop. Even as researchers began warming up to psychedelics again, studying psilocybin and MDMA for PTSD and depression, LSD remained the difficult older sibling at the table.

Yet scientists never stopped being fascinated by what LSD does to the brain at a biological level. Strip away the hallucinations, the ego dissolution, the carpet-pattern demons, and you find something genuinely extraordinary: LSD has a powerful ability to grow brain cells and repair damaged neural connections. It does what most psychiatric drugs can’t even attempt.

So a team led by chemistry professor David Olson asked a question that now looks like one of the most productive questions in recent neuroscience. What if you could keep that healing power and ditch everything else?

The Tire Rotation That Changed Everything

Olson and his colleagues spent nearly five years on a 12-step chemical process to find out. What they produced was a compound called JRT, named after Jeremy R. Tuck, the graduate student who first synthesized it.

JRT looks almost identical to LSD on paper. Same molecular weight. Same overall shape. But move two atoms into different positions within LSD’s molecular structure, and you get something that behaves in a profoundly different way.

“Basically, what we did here is a tire rotation,” said Olson. “By just transposing two atoms in LSD, we significantly improved JRT’s selectivity profile and reduced its hallucinogenic potential.”

A tire rotation. Two atoms. And what came out was a compound that, in early animal studies, healed brain damage caused by chronic stress, slashed depressive symptoms at a fraction of the dose currently needed, and, perhaps most astonishingly, opened a door into a patient population that no psychedelic has ever been able to safely enter.

Why the Brain Breaks Down

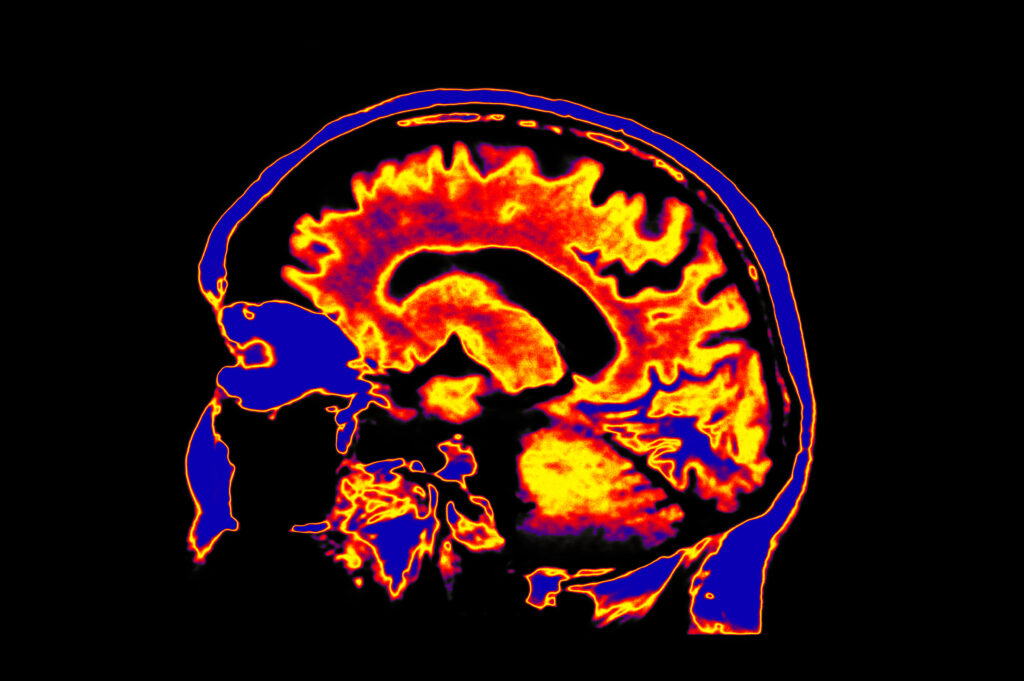

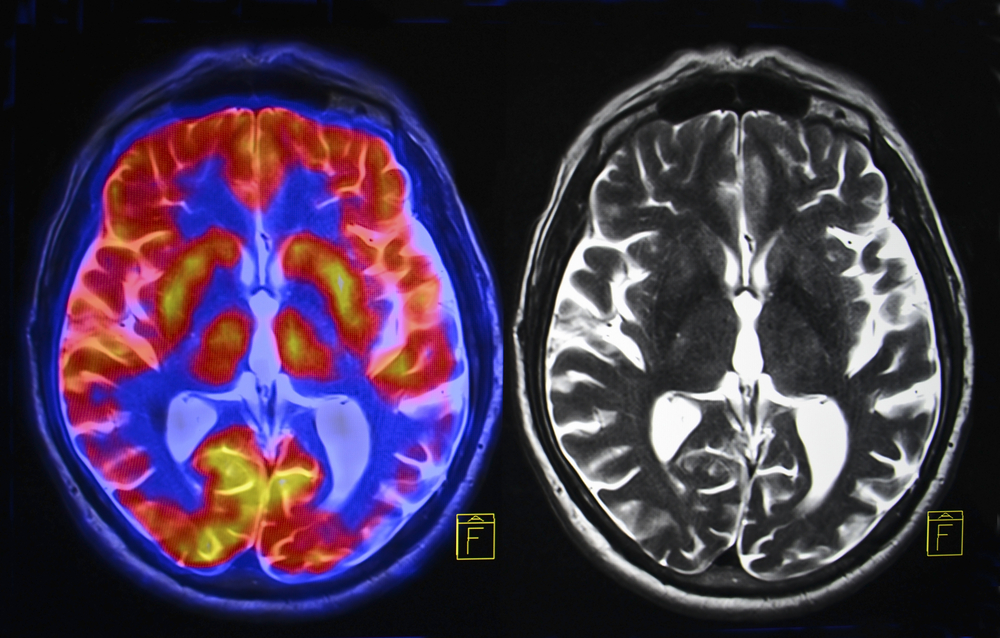

Before getting to what JRT can do, it helps to understand what it’s fixing. When you live under chronic stress, or when mental illness takes hold, parts of your brain physically shrink. Dendrites, the tiny branch-like extensions that neurons use to communicate with each other, lose density. Synapses weaken. Connections that once fired clearly start to fray.

Doctors call this synaptic loss and cortical atrophy. You might call it the hardware of the brain going bad. Depression, addiction, and schizophrenia all share this feature. And here’s the frustrating part: most psychiatric medications don’t fix it. Antidepressants can adjust your brain chemistry, but they don’t rebuild what stress tore down. Antipsychotics can quiet the worst symptoms of schizophrenia, but they leave the structural damage untouched, and they often bring their own brutal side effects: emotional blunting, cognitive decline, and significant weight gain. JRT appears to do something different. It goes after the hardware itself.

What JRT Actually Does Inside the Brain

JRT belongs to a class of compounds called psychoplastogens. Drugs in this category rapidly promote structural repair in the cortex, the region of the brain most responsible for thinking, decision-making, and emotional regulation.

When researchers gave JRT to mice, a single dose produced a 46% increase in dendritic spine density and an 18% increase in synapse density in the prefrontal cortex within 24 hours. To understand how striking those numbers are, consider that current gold-standard antidepressants take weeks to show any effect, and none of them produce changes like that at all.

JRT also rescued brain damage caused by chronic stress. Mice that had been given corticosterone daily for 20 days, mimicking the effects of prolonged psychological stress, showed dramatic dendritic spine loss. One dose of JRT reversed it.

JRT does all of this by binding with high selectivity to serotonin receptors, specifically the 5-HT2A receptors linked to cortical neuron growth. Unlike LSD, it doesn’t touch dopamine receptors, histamine receptors, or adrenergic receptors. Less scatter means fewer side effects and a cleaner path to the brain regions that need help most.

The Population Nobody Could Reach

Here’s where the story takes a turn that researchers in psychiatry will find hard to overstate. People with schizophrenia, or even a family history of psychosis, cannot take psychedelics. Not as a precaution. As a hard medical rule. Emergency room visits involving hallucinogens correlate with a greater risk of developing schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Recent clinical trials of psilocybin for depression excluded roughly 95% of volunteers because too many had contraindications related to psychosis risk.

Schizophrenia affects approximately 0.5% of the world’s population. Its symptoms fall into three categories: positive symptoms like hallucinations and delusions, negative symptoms like anhedonia and social withdrawal, and cognitive symptoms like impaired attention and working memory. Current antipsychotics manage the positive symptoms reasonably well. For the negative and cognitive symptoms, they barely move the needle. JRT took direct aim at both.

“No one really wants to give a hallucinogenic molecule like LSD to a patient with schizophrenia,” Olson said. “The development of JRT emphasizes that we can use psychedelics like LSD as starting points to make better medicines. We may be able to create medications that can be used in patient populations where psychedelic use is precluded.”

In mice, JRT reduced social withdrawal and cognitive fog associated with schizophrenia. It did not trigger behaviors linked to psychosis. It did not induce the head-twitch response that researchers use to measure hallucinogenic activity in animals. When researchers checked for gene expression patterns associated with schizophrenia, LSD caused them to spike. JRT left them unchanged.

JRT also preempted LSD’s hallucinogenic effects outright. When mice received JRT as a pretreatment before being given LSD, the LSD-induced hallucinogenic response was completely blocked. A drug that not only avoids causing psychosis but also actively counters it.

100 Times Stronger Than Ketamine

For anyone who has followed the conversation around fast-acting antidepressants, ketamine has been the benchmark. Approved for treatment-resistant depression, ketamine works faster than traditional antidepressants and has given hope to patients who ran out of other options. JRT left ketamine in the dust.

In a standard test used to measure antidepressant potential in rodents, JRT produced antidepressant effects at doses roughly 100 times lower than the minimum effective dose of ketamine. One hundred times. At a fraction of the dose, JRT decreased immobility and increased active coping behaviors in every dose group tested.

Researchers then measured anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure, and one of the most debilitating features of both depression and schizophrenia. Mice exposed to chronic stress that had lost their normal preference for sweet water regained it after JRT treatment. Rats subjected to cold-water stress showed restored reward responsivity in a behavioral task that translates with unusual accuracy to human depression, and those effects lasted at least three days after a single dose, even when the stress continued.

What’s more, JRT cleared the bloodstream within two hours of administration. Yet its effects on mood and cognition persisted long after the drug was gone. When a drug can change the brain’s structure rather than just its chemistry in the moment, it doesn’t need to stay in your system to keep working.

Cognitive Flexibility: Addressing What Others Ignore

One of the most overlooked aspects of serious mental illness is what it does to thinking. Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder often show marked deficits in cognitive flexibility, specifically the ability to update their responses when the rules of a situation change. Standard treatments do almost nothing about it.

Researchers exposed mice to unpredictable mild stress and then gave them a reversal learning task, a test of cognitive flexibility. Stressed mice failed at it. Stressed mice given a single dose of JRT did not. JRT completely rescued the cognitive deficit induced by stress, with no difference in their ability to perform the basic discrimination task.

Cognitive flexibility connects to how people function in relationships, workplaces, and daily life. Any drug that restores it in populations where it breaks down could matter in ways that medication trial results rarely capture.

Science Isn’t Done With This Molecule Yet

JRT has not been tested in humans. What happens in mice and rats doesn’t always translate, and the road from preclinical success to an approved medication is long, expensive, and full of failure. No one will write a JRT prescription for years, possibly decades.

Olson and his team know this. They are currently testing JRT in additional disease models, working to improve its synthesis, and building new analogues of the compound that may perform even better across a wider range of conditions.

“JRT has extremely high therapeutic potential,” Olson said. “Right now, we are testing it in other disease models, improving its synthesis, and creating new analogues of JRT that might be even better.”

One area worth watching is JRT’s partial agonism at the 5-HT2B receptor. Chronic stimulation of that receptor has been linked to cardiac valve problems in other drugs, and researchers will need to assess whether JRT crosses that line at therapeutic doses. Science, even at its most exciting, carries unresolved questions.

Two Atoms and What They Mean

Step back from the molecular chemistry for a moment and consider what this story is really about. For decades, psychedelics sat outside the boundaries of legitimate medicine, written off by policy and stigma. As researchers quietly began opening those doors again, they kept running into the same wall: hallucinations, psychosis risk, legal barriers, frightened patients, and frightened doctors.

JRT suggests a different path. You don’t need the trip to get the healing. You don’t need to ask a patient with schizophrenia to accept a psychosis risk to treat their condition. You might be able to take the most controversial molecule of the twentieth century, move two atoms, and arrive somewhere medicine has never been before.

A drug that rebuilds the brain’s architecture. A drug that works where others fail. A drug born from a tire rotation inside a laboratory where someone dared to ask what LSD could become if it wasn’t so committed to being LSD. That question, and those two atoms, may end up mattering enormously.

Loading...