“If you’re that depressed, reach out to someone. And remember, suicide is a permanent solution to temporary problems.” – Robin Williams

He made the world laugh so hard it forgot its sadness—if only for a moment.

But what happens when the one who brings joy can no longer find his own?

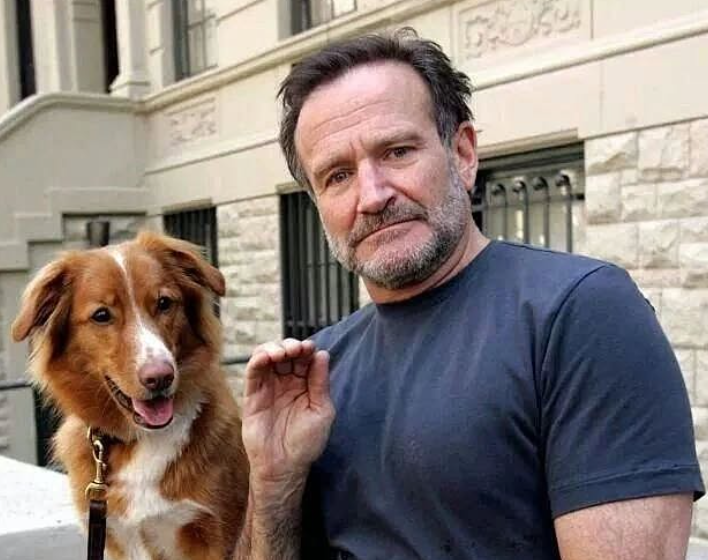

Robin Williams lit up every screen he touched with a rare kind of brilliance—the kind that doesn’t just entertain, but heals. He was a storm of energy, improvisation, and empathy. The man could move from Shakespeare to slapstick in the same breath and make it feel like a spiritual act.

So when the news broke that he had taken his own life, the world paused. A collective ache pulsed through people who had never met him, yet felt they knew him. How could someone who seemed to have it all—fame, love, purpose—fall into such a deep, unseen darkness?

It’s easy to call it depression and move on. Easier still to say, “He should’ve reached out.”

But the truth is messier. And far more urgent. Because what took Robin Williams wasn’t just despair—it was a rare, brutal disease that stole his mind long before it took his body. A disease that most of us have never heard of, but should.

This isn’t just a story about one man’s tragedy. It’s about what we miss when we only look at the smile and not what’s behind it. It’s about how even the brightest lights can burn out in silence.

The Brightest Light in the Room

Robin Williams didn’t just walk into a room—he filled it. His voice, his laughter, his wild improvisations seemed to stretch beyond the frame, making screens feel alive. Whether as the eccentric Genie in Aladdin, the soulful therapist in Good Will Hunting, or the cross-dressing nanny in Mrs. Doubtfire, Robin didn’t act; he embodied emotion. Millions connected to his joy because he gave so much of it away.

But joy is not the same as peace.

When the world learned that Robin Williams had died by suicide on August 11, 2014, the reaction wasn’t just grief—it was confusion, disbelief. The man who made everyone else laugh couldn’t find a reason to stay? It didn’t make sense. And that confusion echoed even louder in the voices of those who knew him best.

His children described feeling “stripped bare.” His son Zak called him both a father and a best friend. Zelda, his daughter, confessed she would never understand how someone “so loved could not find it in his heart to stay.” The sorrow wasn’t just personal—it felt cosmic, like a constellation had blinked out.

Tributes poured in across the globe: chalked quotes on park benches in Boston, flowers outside his home in Tiburon, signs at comedy clubs that read “Make God Laugh.” Friends and co-stars mourned not just his talent, but his warmth. “A generous soul,” Meryl Streep said. “A Niagara of wit,” Alan Alda called him. But what stood out most was what people repeated again and again: he was kind. Gentle. Giving. Good.

Robin’s death didn’t just take a man from the world—it exposed how little we often know about the inner world of those we think we understand. It reminded us that fame is not a shield, and that laughter can sometimes be camouflage.

What We Didn’t See: The Private Struggles

By the early 2010s, his career had slowed. His return to television with The Crazy Ones—a CBS sitcom that initially seemed like a comeback—quickly lost steam. Critics noted his performance lacked its old spark. Some described him as “exhausted.” Ratings slipped, and within a year, the show was cancelled. Behind the scenes, Robin was quietly unraveling.

He had always been driven by work. Friends said performing wasn’t just his passion—it was his lifeline. When he worked, he lit up. But now the roles were fewer, the laughter less certain. His old confidence had given way to insecurity. A former dynamo, he had started to doubt even the one thing he had always been sure of: his ability to be funny.

His home life offered little refuge. Robin was adjusting to a relatively new marriage, coping with the guilt of two divorces, and navigating the layered dynamics of blended families and private pain. His eldest son, Zak, later reflected that he should have visited more during that time: “I think that was a very lonely period for him.”

Then came the storm of unexplained symptoms. Insomnia. Digestive issues. Tremors. Panic attacks. Visual hallucinations. Freezing mid-motion. Forgetting lines. Robin became trapped in a body—and a mind—he no longer recognized. He told his wife he felt like his brain needed a “reboot.” He tried therapy, physical training, even self-hypnosis. But it was like trying to put out a fire in the dark when you don’t know where the flames are.

At times, he could still rally his warmth. He’d reach out to friends like Billy Crystal and shower them with affection, often calling repeatedly after they’d said goodbye—“Just wanted to say I love you,” then five minutes later, “Was I too sappy?”

But his friends saw it, even if they didn’t understand it. “Something’s wrong,” said his longtime co-star Pam Dawber after filming with him again. “He’s lost the spark.” Others described a “thousand-yard stare,” a man who seemed physically present but emotionally distant.

He felt shame. Shame about aging. About perceived failures. About how his illness was affecting those around him. Even when his children reassured him of their love, he couldn’t accept it. “He was firm in his conviction that he was letting us down,” Zak later said.

All the while, Robin was still trying to protect others from the full weight of his suffering. And so, the world kept seeing the smile. The world kept laughing. But inside, he was slipping further into a reality he couldn’t control—and didn’t yet understand.

The Invisible Enemy: Lewy Body Dementia

Three months before his death, Robin Williams was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. It explained some symptoms—tremors, stiffness, sluggishness—but not the crushing anxiety, the paranoia, the confusion, the terrifying hallucinations, or the loss of his ability to perform the very skill that had defined his existence: making people laugh.

In truth, Robin was misdiagnosed. Only after his death would the full story come to light.

The autopsy revealed that he had been living with Lewy body dementia—an aggressive, incurable brain disease that affects an estimated 1.4 million people in the United States. Yet it remains largely misunderstood and frequently misdiagnosed, even by experts.

Lewy body dementia (LBD) occurs when abnormal protein deposits—called Lewy bodies—build up in the brain, disrupting cognitive and motor functions. It’s a cruel mix of symptoms often seen in both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s patients: memory loss, hallucinations, mood swings, tremors, rigidity, sleep disruption, and rapid mental decline. But unlike Alzheimer’s, where memory fades gradually, LBD can feel like a nightly ambush—waves of confusion, paranoia, and terrifying delusions that come and go without warning.

As Dr. Bruce Miller, a leading neurologist familiar with Robin’s case, put it:

“This was about as devastating a form of Lewy body dementia as I had ever seen. It really amazed me that Robin could walk or move at all.”

Robin was aware that something was terribly wrong. He couldn’t remember lines. He froze mid-conversation. He cried in the arms of his makeup artist after every shoot. He couldn’t sleep, and when he did, he was shaken by vivid, often disturbing dreams. He started sleeping in a separate bedroom, afraid his nighttime thrashing might harm his wife.

When a friend suggested he try doing stand-up again to lift his spirits, Robin broke down and whispered, “I can’t. I don’t know how anymore.”

And perhaps most painfully, he didn’t know what was happening to him. His mind was unraveling, but no name had been given to the thing stealing him from himself. He planned to undergo neurocognitive testing, but never made it to the appointment. His widow, Susan Schneider Williams, later reflected, “I think he thought: I’m going to get locked up and never come out.”

The tragedy wasn’t just that Robin died by suicide. It was that he died fighting a battle he didn’t even know he was in. Against an invisible enemy no one had named. Alone, in a mind that was slowly turning against him, while the world still believed he was just sad, or stressed, or “past his prime.”

He wasn’t weak. He wasn’t selfish.

He was sick. And no one knew how sick he really was.

Beyond the Diagnosis: What His Death Teaches Us

Robin Williams’ death wasn’t just the loss of a beloved entertainer—it was a wake-up call. A mirror held up to our culture’s understanding of mental health, identity, and the limits of how well we really know each other.

Too often, we look for simple explanations to complex pain. Depression. Addiction. Career failure. But these words, while part of his story, were not its conclusion. The truth was more tangled—and more common than we’d like to admit.

Because Robin’s story is not only about Lewy body dementia. It’s also about what we miss when we rely on surface impressions. It’s about how good someone can be at hiding their suffering, even in plain sight. Especially when they’ve spent a lifetime learning how to do just that—making others smile so they don’t have to show their own sorrow.

In the final months of his life, Robin was surrounded by people who loved him. Friends called. Family reached out. But love alone isn’t always enough—not when illness clouds your sense of self, or shame whispers that you’re a burden, or confusion makes the world feel unreal. Robin didn’t isolate because he didn’t care. He isolated because he didn’t know how to explain what he couldn’t understand.

And in this, he becomes painfully relatable.

How many people in your life might be carrying silent pain right now? How many are showing up, smiling, cracking jokes—while their world is quietly unraveling behind closed doors? Pain doesn’t always announce itself. Often, it disguises itself as “I’m fine.”

His death reminds us that suffering is not always visible. That mental and neurological illness don’t always come with warning signs we’re trained to recognize. And that when people say, “Reach out,” it needs to go both ways. Sometimes those in pain don’t have the words—or the energy—to explain themselves.

Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

To truly honor Robin Williams’ story, we must do more than mourn his passing—we must understand the illness that silently dismantled his mind. Lewy body dementia (LBD) is not rare, but it is often overlooked or mistaken for something else. And that confusion can cost lives.

What is Lewy Body Dementia?

Lewy body dementia is the second most common type of progressive dementia after Alzheimer’s disease, accounting for up to 15% of all dementia cases, according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association. It involves the build-up of abnormal protein deposits called Lewy bodies in the brain, disrupting chemical signals and damaging memory, behavior, movement, and perception.

Robin’s case was described by experts as one of the most severe they had seen—an unusually fast-moving and overwhelming form of the disease. And like many others, he was misdiagnosed, treated for the wrong illness, and left feeling increasingly confused and broken without a clear reason why.

Common Symptoms of LBD

Lewy body dementia mimics other illnesses—especially Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s—making it hard to recognize early. Symptoms vary, but commonly include:

- Cognitive issues: memory problems, disorganized thinking, poor judgment

- Visual hallucinations: often one of the earliest and most distinct signs

- Motor symptoms: tremors, muscle rigidity, difficulty walking, slowed movement (similar to Parkinson’s)

- Sleep disturbances: including REM sleep behavior disorder (acting out dreams)

- Severe mood changes: depression, anxiety, paranoia, emotional swings

- Fluctuating alertness: periods of confusion that come and go unpredictably

- Autonomic dysfunction: problems with blood pressure, digestion, or temperature regulation

In Robin’s case, many of these symptoms appeared—but didn’t make sense together. One day he might seem better; the next, he was lost in a mental fog or wracked with fear and delusions. That inconsistency is one of LBD’s cruel trademarks.

Diagnosis: Why It’s So Difficult

There is currently no single test for LBD. Diagnosis is made through a combination of clinical evaluations, neurological exams, imaging (like PET or MRI scans), sleep studies, and ruling out other disorders. Misdiagnosis is common. LBD is frequently mistaken for:

- Parkinson’s disease

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Depression

- Psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia

Robin was diagnosed with Parkinson’s just three months before his death. The deeper, more complex truth of his condition only surfaced during the autopsy. As his widow Susan later shared, “It was not depression that killed Robin. Depression was one of 50 symptoms, and it was a small one.”

Is There a Cure?

There is no cure for Lewy body dementia.

Treatment focuses on managing symptoms and improving quality of life. This may include:

- Medications: to ease movement issues (like Levodopa), mood disorders (antidepressants), or hallucinations (very carefully, as some antipsychotics worsen LBD)

- Occupational and physical therapy: to maintain mobility and daily function

- Cognitive interventions: memory aids, mental stimulation

- Supportive care: counseling, family support, creating safe environments

But treatment is fragile. Many medications used in Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s patients can trigger dangerous side effects in LBD patients. That’s why early and accurate diagnosis is critical.

A Call to Compassion: What You Can Do

We may never fully understand the pain that Robin Williams carried, but we can choose to learn from it. Not with pity, not with passive sadness—but with action. Because if someone like Robin—beloved, successful, and surrounded by people who adored him—can still feel lost and unseen, then anyone can.

That’s the truth we must face: kindness alone isn’t enough if it’s silent.

Compassion has to show up. It has to speak.

It has to ask the uncomfortable questions.

So what can you do?

Check in—really check in—on the people in your life, especially the ones who seem “strong.” Especially the ones who make others laugh. Especially the ones who never ask for help. Ask how they’re sleeping, how they’re feeling, what’s heavy on their hearts. And if they deflect, ask again. Be annoying if you have to. Love loud.

Learn about illnesses like Lewy body dementia, depression, and other invisible conditions. Awareness doesn’t just save lives—it restores dignity. It tells people, You’re not crazy. You’re not weak. You’re not alone.

Support causes that fund research for neurological and mental health disorders. Speak up against stigma when you hear it. Be the kind of person someone could trust with their pain.

And if you are the one hurting: stay. Reach out. There is no shame in struggling. There is no shame in needing help. As Robin himself once said, “Suicide is a permanent solution to temporary problems.” But if those problems feel anything but temporary, that’s all the more reason to not face them alone.

The world is still darker without him. But the light he gave us? It’s not gone—it’s in us now. So pass it on. Shine it forward. And let your compassion be so loud, that no one in your life ever has to wonder if they matter.

Because they do.

You do.

Featured Image from Instagram @robinwilliam

Loading...