Study Reveals Reading is a Complex, Flexible Brain Process Involving Multiple Interacting Neural Networks

Ever paused to marvel at the quiet miracle unfolding behind your eyes each time you trace a line of print? A mere squiggle on a page ignites an invisible fireworks show—more than three thousand minds, scanned in 163 separate studies, prove it. Letters spark like single notes in a piano’s higher register; words thrum like full chords; whole paragraphs swell into orchestral crescendos that recruit vision, memory, movement, meaning all at once.

Yet most of us glide through text the way fish glide through water: unaware of the vast currents carrying us. Why does a nonsense word like “blim” pull your brain into sounding-out mode, while a familiar friend like “love” glides straight to meaning? How can silent reading feel tranquil when your frontal lobes are firing as fiercely as if you were speaking out loud? And what is the cerebellum—once thought to choreograph only our limbs doing waltzing with syllables?

These questions aren’t trivia; they’re keys to a larger truth: every page you read is a workout in cognitive flexibility, a real-time remix of neural networks that keeps your mind resilient, adaptable, alive. Turn the page your brain is already dancing.

Why Reading Isn’t What It Seems

We treat reading as routine like flipping a light switch or tying our shoes. It’s something we learned in childhood, practiced into second nature, and rarely stop to question. But beneath its surface lies a process so intricate, so dynamic, that even the best computers struggle to replicate it with grace.

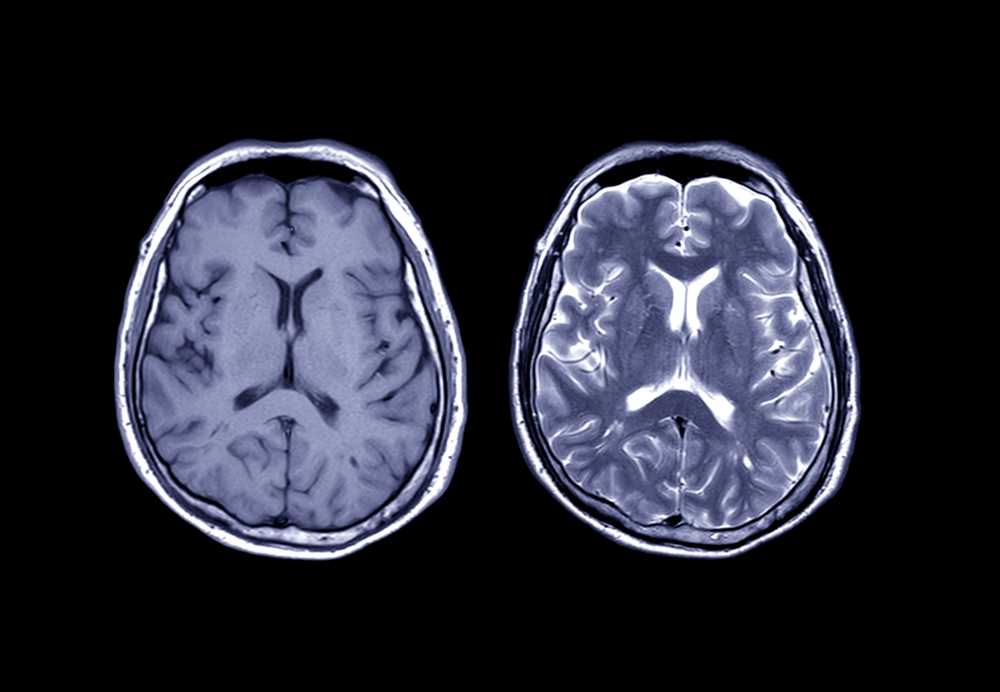

A landmark meta-analysis from the Max Planck Institute uncovered just how layered the act of reading truly is. By analyzing brain scans from over 3,000 people across 163 studies, researchers discovered that reading isn’t one static skill it’s an ever-shifting choreography of specialized brain regions working in concert. It’s not that the brain does more when a text becomes harder; it does something different entirely.

Reading a single letter lights up a small visual area. A full word? That draws in frontal and parietal regions to analyze structure and meaning. Dive into a sentence, and your brain recruits centers responsible for grammar, rhythm, even predictive processing. When you engage with a paragraph or page, your working memory steps in, helping you track ideas, link concepts, and imagine what’s coming next.

What’s more, how you read changes how your brain responds. Reading aloud activates your auditory system and the motor regions that control speech. Silent reading? That’s not passive it demands that your brain suppress vocalization, form internal speech, and direct attention using executive control networks. In other words, your brain must speak without speaking, hear without hearing.

Even the cerebellum, long considered the realm of balance and motion, joins the act. It’s especially active during silent reading, hinting that comprehension and coordination may be more deeply linked than we ever thought.

Reading, then, isn’t simple at all it’s strategic. It’s your brain selecting the right network at the right moment for the right kind of word. Behind every sentence is a cascade of decisions, pathways, and shifts a quiet storm of precision. And perhaps the most astonishing part? We make it look easy.

How Different Brain Regions Collaborate

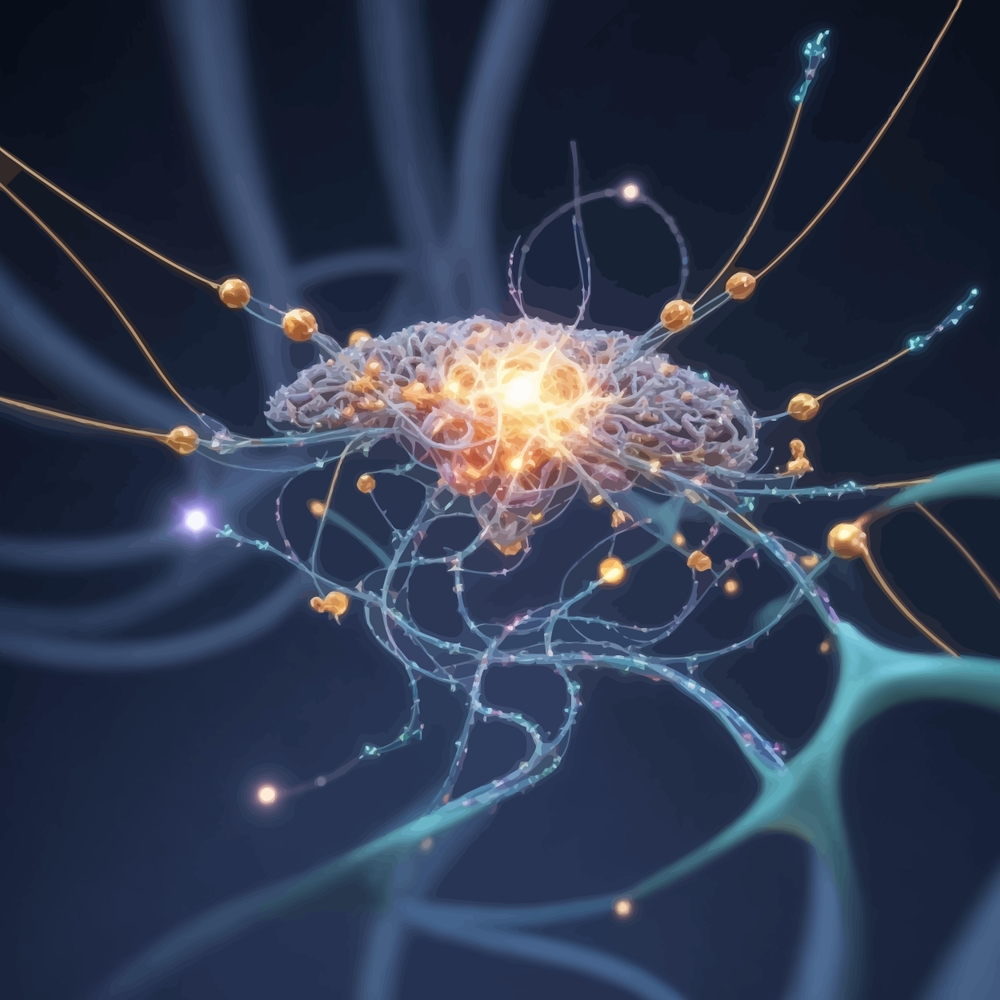

Imagine a symphony where each instrument knows exactly when to come in not because there’s a single conductor, but because every musician senses the rhythm, the mood, the message. That’s what happens in your brain when you read. It’s not one area playing a solo it’s an ensemble performance, dynamically tuned to the kind of reading you’re doing in that moment.

Thanks to brain imaging studies, we now know that reading engages a sprawling network, primarily in the left hemisphere, but with surprising guest appearances from unexpected regions. Each part of the network has a distinct role to play visual areas recognize shapes, temporal regions process sounds, parietal areas track structure and space, and frontal lobes help interpret meaning, intent, and context.

For instance, when you read a word like run, your brain might instantly connect it to movement, urgency, or even a childhood memory of recess. That seemingly instant recognition? It requires the angular gyrus and inferior temporal sulcus regions known for translating visual symbols into concepts and emotional associations. Then, if the word appears in a sentence She runs toward the light your brain calls in deeper layers of interpretation, analyzing syntax and predicting outcomes. That’s where networks responsible for working memory, attention, and semantic integration come in.

And it’s not just the word itself it’s how familiar it is. Real words you know by heart light up areas tied to memory and meaning. But throw in a made-up word like drelf, and suddenly your brain reroutes through phonological circuits, trying to “sound it out.” This two-pathway system one for known words, one for decoding unfamiliar ones shows that your brain isn’t just reading; it’s choosing how to read.

Even the cerebellum, classically associated with motor control, plays a subtle but significant role. During silent reading, it activates in ways that suggest it helps fine-tune internal speech and coordinate complex sequences of thought, much like it helps a pianist move smoothly from key to key.

So reading isn’t a single act it’s a conversation among specialized brain systems, each listening, responding, and adapting. Every sentence you read is like a score, and your brain interprets it in real time, layering perception, memory, emotion, and prediction into a seamless experience. It’s no wonder we can lose ourselves in books because reading, quite literally, moves us.

The Brain’s Dual Reading System

Every time you read a word, your brain has a choice one that happens in a fraction of a second but reveals a deep truth about how we process language: there’s more than one road to meaning.

Neuroscience calls them the dual routes of reading. One path is like a well-paved highway: fast, familiar, automatic. The other is more like a hiking trail slower, more effortful, but essential when you’re navigating unfamiliar terrain. And your brain switches between them constantly, depending on what’s in front of you.

Let’s say you encounter the word tree. You’ve seen it a thousand times. Your brain doesn’t need to break it down letter by letter. Instead, it takes the lexical-semantic route recognizing the word as a whole, tapping into your mental dictionary, and instantly retrieving its meaning, pronunciation, and associations. It’s fast, fluid, and deeply tied to memory.

Now imagine reading a nonsense word like sproke. Your brain can’t look it up in memory because it doesn’t exist there. So it calls on the phonological route decoding the word by sounding it out, syllable by syllable, using learned spelling-sound rules. It’s slower, but it’s the path that helps us read new words, learn new languages, or decipher names we’ve never seen before.

What’s fascinating is how your brain decides which route to take without you ever noticing. This decision is influenced by word familiarity, spelling patterns, and even context. And the two routes aren’t rivals—they’re teammates, working together to strike a balance between efficiency and comprehension.

Recent studies show that when a word is tricky maybe it has irregular spelling, like yacht, or low imageability your brain recruits help from areas responsible for meaning (like the angular gyrus and inferior temporal sulcus) to support the phonological system. This interplay echoes what connectionist models of reading have long suggested: semantics and sound aren’t separate silos; they collaborate.

It’s this collaborative flexibility that makes human reading so powerful. Unlike most AI models, which rely on fixed processes, our brains adapt in real time, picking the most efficient or effective route depending on the word, the sentence, and even the emotional tone.

And in that fluid back-and-forth between decoding and recognition, between sound and meaning we see the brilliance of a reading brain that not only processes language, but understands it.

What Reading Reveals About the Brain

Reading doesn’t just reveal the words on a page—it reveals something far deeper: how flexibly and intelligently the human brain adapts. Every shift between letters and meaning, every leap from phonics to understanding, is a reflection of one of the brain’s most vital abilities: cognitive flexibility.

Cognitive flexibility is the mental muscle that allows us to switch perspectives, adapt strategies, and respond to the unexpected. It’s what helps a child learn to read cat and hat by sounding out the letters and later recognize that colonel doesn’t follow those rules at all. It’s the same skill we draw on when we change our mind, solve a new problem, or adjust to life’s curveballs. In that sense, every act of reading is training for life.

Neuroscientists have found that this flexibility is supported by a dynamic network of brain regions the lateral frontoparietal network, the midcingulo-insular network, and frontostriatal loops that shift their connectivity depending on the task at hand. These networks don’t just activate during reading; they reconfigure in real time, adjusting the strength and direction of communication between brain areas depending on whether you’re reading a poem, decoding a technical manual, or interpreting a metaphor.

Silent reading, for example, activates executive networks that suppress vocalization and simulate inner speech requiring you to “hear” the words in your mind without saying them aloud. The brain toggles between default and active modes, balancing comprehension with attention. And the better this flexibility, the better the reading performance. In fact, people who score higher on reading comprehension tasks tend to show greater variability and responsiveness in their brain networks hallmarks of neural agility.

But this ability isn’t fixed. Just like a muscle, it can be strengthened or it can atrophy. Conditions like ADHD, autism, mood disorders, and dementia all show disruptions in the very systems that enable flexible reading and thinking. When the brain loses its ability to shift strategies or adjust to new information, the effects ripple beyond reading, into memory, decision-making, and emotional regulation.

That’s why reading is more than a literacy skill. It’s a living demonstration of how adaptable, resilient, and self-organizing the human mind can be. It shows us that intelligence isn’t just about knowing it’s about adjusting, choosing, and evolving in response to what’s in front of us.

And in that dance between focus and fluidity, comprehension and creativity, reading becomes not just a tool for learning but a mirror of the mind’s highest potential.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

We live in an age of constant input scrolling feeds, breaking news, blinking alerts. But amidst the noise, reading remains one of the few acts that asks something deeper of us: to slow down, to reflect, to engage fully with meaning. And now, neuroscience shows that reading does more than inform or entertain it tunes the very circuits that help us adapt, focus, and grow.

Why does this matter now more than ever?

Because flexibility isn’t just a cognitive luxury it’s a survival skill. In a world defined by rapid change, misinformation, and mental overload, the ability to switch perspectives, grasp nuance, and decode complexity is essential. The very networks that allow us to read a difficult sentence or infer the tone behind a line of poetry are the same ones we rely on to make decisions, navigate conflict, and empathize with others.

And yet, many of us are reading less at least deeply. Skimming has replaced comprehension. Clickbait has overtaken critical thought. But reading, real reading, is an act of mental resistance. It invites us to stretch to make room for ambiguity, for imagination, for truth that can’t be reduced to a headline.

For students, reading builds neural flexibility that supports not only academic success but emotional intelligence. For adults, it strengthens memory and sharpens decision-making. For aging minds, it’s a cognitive lifeline slowing decline, preserving attention, and nurturing curiosity. And for all of us, it’s a daily opportunity to exercise the very systems that make us capable of growth.

This isn’t just about literature or literacy. It’s about what kind of minds we’re cultivating. Minds that can adapt. That can question. That can listen.

What’s Your Brain Learning From the Page?

Every time you read, your brain is not just gathering information it’s becoming something new. It’s learning how to shift gears, to juggle meaning and memory, to stay present while imagining something far beyond the moment. Reading is not a passive act. It’s a rehearsal for life.

So ask yourself:

When was the last time you really read not skimmed, not scanned, but sat with a sentence long enough to let it change you?

In a world that rewards speed, reading teaches depth. In a culture obsessed with certainty, reading nurtures complexity. And in a time when many minds are becoming rigid trapped in algorithms and echo chambers reading keeps yours pliable, curious, alive.

This is more than inspiration. It’s an invitation.

Choose texts that challenge you. Reread paragraphs that make you pause. Read things that make you uncomfortable, and notice how your brain shifts how it negotiates meaning, holds tension, makes space for something new. That is the quiet miracle of flexibility in motion.

You are not just a reader. You are a rewiring system. A mind that can learn, unlearn, and reimagine—one page at a time.

So the next time you open a book or click an article, don’t just ask, What am I reading?

Ask instead: What is this teaching my brain to do?

Because what you practice when you read attention, empathy, adaptability is what you’ll carry into everything else.

And the world needs more minds that can read between the lines and rewrite what’s possible.

Loading...