A Printing Mistake in 1525 Accidentally Invented How We Think About Borders

I want you to consider something. Every time you look at a map showing national borders, every time you hear politicians argue about territorial sovereignty, every time you accept without question that countries have fixed boundaries, you are living inside an idea. That idea traces back, at least in part, to a 500-year-old Bible map that was printed completely backward.

Here is what happened. Lucas Cranach the Elder created the first map ever published inside a Bible. Christopher Froschauer printed it in his 1525 Old Testament. And somehow, nobody in that workshop noticed they had reversed the entire thing. The Mediterranean Sea appeared east of Palestine instead of west.

How could trained professionals miss such an error? Because Europeans knew almost nothing about that part of the world. Geography was a mystery. And yet, despite being fundamentally wrong, Cranach’s map would go on to change everything.

Why Bibles Never Had Maps Before 1525

Before we go further, you need to understand why maps in the Bible were revolutionary. For more than a thousand years, ordinary people never read scripture themselves. Priests read the Bible aloud in Latin during worship services. Congregations listened. Individual believers had no direct relationship with the physical text.

Protestantism changed that equation. Reformers insisted that every person should read scripture in their own language. They believed faith came through personal engagement with sacred texts, not through church hierarchy. Reading the Bible became central to worship itself.

Once people started reading for themselves, a new question emerged. If these stories really happened, where did they happen? Could we find these places on a map?

Swiss reformers particularly stressed literal interpretation. They wanted proof that biblical events occurred in real time and real space. A map could provide that proof. A map could make ancient stories feel solid and present.

Virtual Pilgrimages From Your Kitchen Table

Here is where things get interesting. During the Reformation, religious images inside churches were banned. Paintings of saints, statues of Mary, elaborate crucifixes, all forbidden. But maps? Maps were permitted.

Suddenly, maps became objects of devotion. Believers who could never afford a pilgrimage to Jerusalem could trace their fingers across Palestine from their own homes. They could pause at Mount Carmel, move to Nazareth, follow the Jordan River, and rest at Jericho.

MacDonald describes how readers experienced these maps as spiritual journeys. In their imagination, they traveled across the landscape and encountered sacred stories as they moved. A farmer in Germany could walk where Jesus walked. A merchant’s wife in Switzerland could stand where Moses stood. All through the power of a printed page.

For people who had never left their villages, never seen the sea, never imagined the desert, these maps opened entire worlds. They transformed abstract faith into concrete geography.

Making Sense of a Messy Biblical Text

Now here is something most people never learn. Biblical descriptions of tribal territories are messy. Joshua chapters 13 through 19 attempt to describe which tribe received which land after Israel conquered Canaan. But contradictions fill those chapters. Boundaries overlap. Cities appear in multiple tribal territories. No coherent picture emerges from the text alone.

Cranach’s map cleaned all of that up. It showed twelve neat territories, each clearly bounded, all fitting together like puzzle pieces. Readers could finally see order where the text offered confusion.

As MacDonald observed in his research, “The map helped readers to make sense of things even if it wasn’t geographically accurate.”

Think about what that means. Accuracy mattered less than clarity. People wanted to believe the Bible described a real, organized world. Maps permitted them to believe it.

Cranach borrowed his tribal divisions from medieval maps that relied on Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian. Josephus had simplified complex realities for Roman audiences. Those simplifications traveled through centuries of Christian mapmaking until they landed in a Zürich print shop.

Medieval Maps Were About Spiritual Inheritance

Before 1525, tribal boundary maps already existed in Christian tradition. Burchard of Mount Sion created detailed maps in the late thirteenth century. Pietro Vesconte produced grid maps in the fourteenth century to accompany crusade literature.

But medieval Christians understood those boundaries differently than we might expect. For them, tribal lines represented spiritual claims, not political ones.

Joshua and Jesus share the same name in Hebrew and Greek. Medieval theologians saw Joshua as a type of Christ, someone who completed what Moses could only begin. Moses led the people through the wilderness but died before entering the Promised Land. Joshua brought them home. In the same way, Christians believed, Jesus brought spiritual fulfillment that the Hebrew scriptures could only promise.

Church fathers like Jerome interpreted tribal land possession as pointing toward heavenly inheritance. Lines on medieval maps symbolized what Christians would possess eternally, not what any earthly government controlled.

How Printing Changed Everything

Manuscript maps stayed confined to monasteries and noble courts. Only the wealthy and educated encountered them. But printing democratized access in ways that transformed society.

Publishers eventually standardized four maps for Protestant Bibles. One appeared at Numbers 33 for wilderness wanderings. Another sat at Joshua 15 for tribal division. A third opened the New Testament, showing Palestine during Jesus’s lifetime. And a fourth concluded Acts with Paul’s missionary journeys.

As Bibles spread through Europe in the seventeenth century, millions of people absorbed these images. They developed shared mental pictures of how sacred space should look. And those pictures carried assumptions about territory, boundaries, and division.

MacDonald argues these maps spread a sense of how the world ought to be organized. Readers internalized the idea that land should be divided into clear portions with firm edges. What started as spiritual symbolism began to feel like natural law.

When Spiritual Lines Became Political Borders

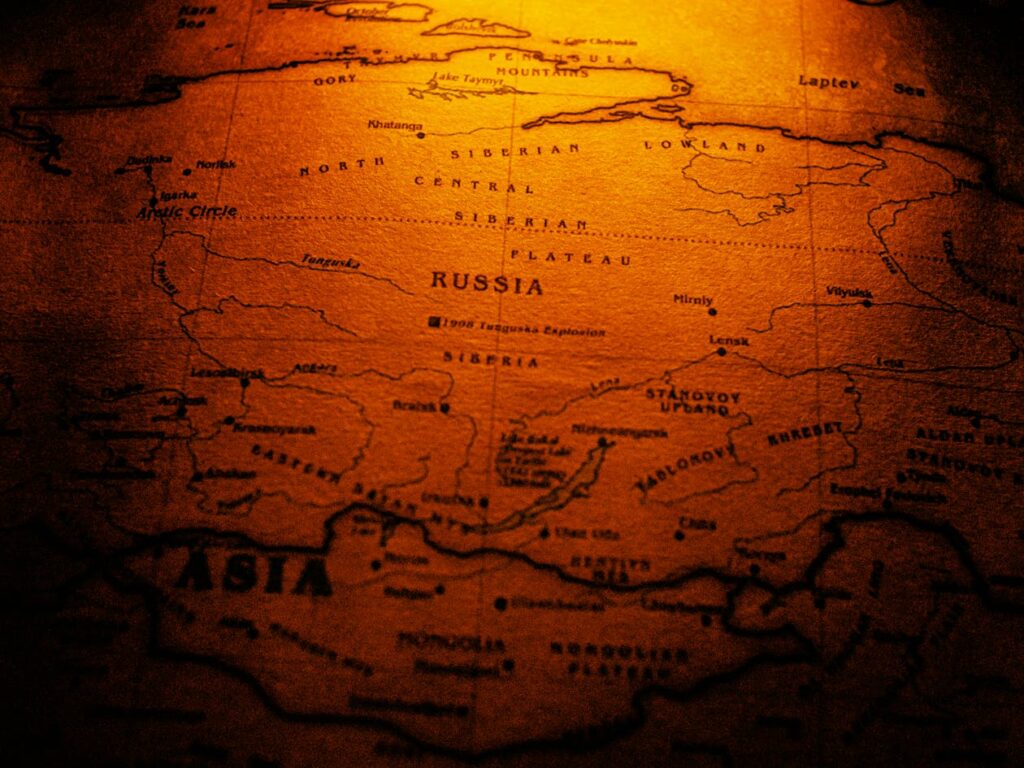

Here is where the story takes its most dramatic turn. Something shifted as boundary lines migrated from Holy Land maps to atlases depicting Europe and the wider world.

Research by James Akerman shows that only 45 percent of maps in 1570 displayed territorial boundaries. By 1658, that number reached 98 percent. In less than a century, mapmakers transformed how they represented political space.

MacDonald’s research reveals something surprising. Maps of Palestine led this revolution rather than following it. Biblical maps were agents of change, not just recipients of ideas developed elsewhere.

What once symbolized divine promises began to symbolize limits of political sovereignty. Lines that meant “Christians will inherit eternal blessings” started to mean “this king controls this territory and that king controls that one.”

People began to imagine that borders carried physical, permanent truth. They forgot that every line on every map was drawn by human hands for human purposes.

John Selden and Legal Invention

By 1635, English jurist John Selden published a treatise arguing that seas could be owned like land. His work, Mare Clausum, used the Bible as evidence for territorial sovereignty.

Selden pointed to Genesis 10, often called the Table of Nations. That chapter lists people descended from Noah’s sons after the great flood. It describes migration and settlement. It says almost nothing about borders or boundaries except for the Canaanites.

Yet Selden read the chapter through his own political assumptions. He saw Noah’s descendants as “private Lords” who “appointed Bounds” over their territories. He transformed vague biblical language about spreading across the earth into legal claims about national ownership.

From Selden forward, commentators imagined Noah surveying the world and assigning plots like Joshua dividing Canaan. A text with almost no border language became a model for organizing humanity into bounded nation-states.

A Cycle Without End

MacDonald captures this dynamic perfectly. Early modern notions of the nation drew from biblical imagery. But those new political theories also changed how people read scripture. Influence flowed in both directions simultaneously. “The Bible was both the agent of change, and its object.”

Consider what that means. People read their assumptions into ancient texts. Then they pointed to those texts as proof that their assumptions were divinely ordained. A perfect circle of self-justification.

Why Border Talk Still Sounds Biblical Today

MacDonald points to a recent U.S. Customs and Border Protection recruitment video. In it, a border agent quotes Isaiah 6:8 while flying above the U.S.-Mexico border in a helicopter. Ancient prophetic words about responding to God’s call become recruitment slogans for territorial enforcement.

When MacDonald asked AI systems whether borders are biblical, both ChatGPT and Google Gemini simply answered yes. No complexity. No historical context. Just a confident affirmation of an idea that developed through centuries of interpretation and reinterpretation.

MacDonald offers a warning worth hearing. “We should be concerned when any group claims that their way of organising society has a divine or religious underpinning because these often simplify and misrepresent ancient texts that are making different kinds of ideological claims in very different political contexts.”

What You Can Learn From a Backwards Map

Return with me to that Zürich workshop in 1525. Workers printed a map with the Mediterranean on the wrong side. Nobody caught the error because nobody knew better. And yet that flawed document helped reshape human consciousness.

Borders that feel eternal are actually invented. Lines that seem obvious are actually chosen. Divisions that appear natural are actually constructed.

You live inside ideas that someone created. Maps taught the Bible, and the Bible taught the maps, in an ongoing dance across five centuries. Every time you look at a national boundary and feel certain it belongs there, remember Cranach’s backwards map.

Remember that the most powerful ideas often arrive disguised as simple facts. And remember that questioning those ideas is not a betrayal of faith or tradition. It is the beginning of wisdom.

Loading...