Scientists Found Aging Wakes Up New Fat-Making Cells That Expand Belly Size, Revealing a Target to Stop It

Why does the belly seem to have a mind of its own once we reach our 40s? You can eat the same foods, hit the gym with the same routine, and still notice your waistline softening, your clothes fitting differently. It’s one of those universal midlife mysteries so common that many accept it as inevitable. But what if the story isn’t about calories or discipline at all?

Scientists are beginning to uncover a hidden biological script running inside our bodies. Beneath the skin, deep in the white fat tissue that wraps our organs, certain cells lie dormant for decades, waiting. Then, somewhere in middle age, they “wake up,” multiplying with surprising force and manufacturing entirely new fat cells. Not just bigger fat cells new ones. Researchers have named them committed preadipocytes, age-enriched (CP-As), and their discovery flips the old story of midlife weight gain on its head.

This isn’t just about looks. Belly fat is one of the strongest predictors of chronic disease, from type 2 diabetes to cardiovascular problems. Understanding why it suddenly blooms in midlife could unlock powerful new ways to protect our health. And now, for the first time, scientists have not only identified the cellular culprit but also a possible switch to stop it.

The Cellular Discovery

For decades, doctors assumed midlife belly growth came mostly from existing fat cells swelling in size. The new research shows something more startling: our bodies actually start making new fat cells at a much faster rate once we hit middle age. Scientists at City of Hope and UCLA pinpointed a unique set of fat stem cells that appear during this stage of life. They’ve been named committed preadipocytes, age-enriched (CP-As) and they’re anything but passive. These cells multiply rapidly and transform into mature fat cells, especially in the belly’s deep visceral tissue.

To see this process in action, researchers tracked fat cell turnover in mice of different ages. Young mice barely created new fat cells. But by “middle age”the rodent equivalent of a human in their 40s over 80% of the belly fat cells were newly formed. This was the first clear evidence that belly expansion is not just storage gone wild but the product of new cellular activity.

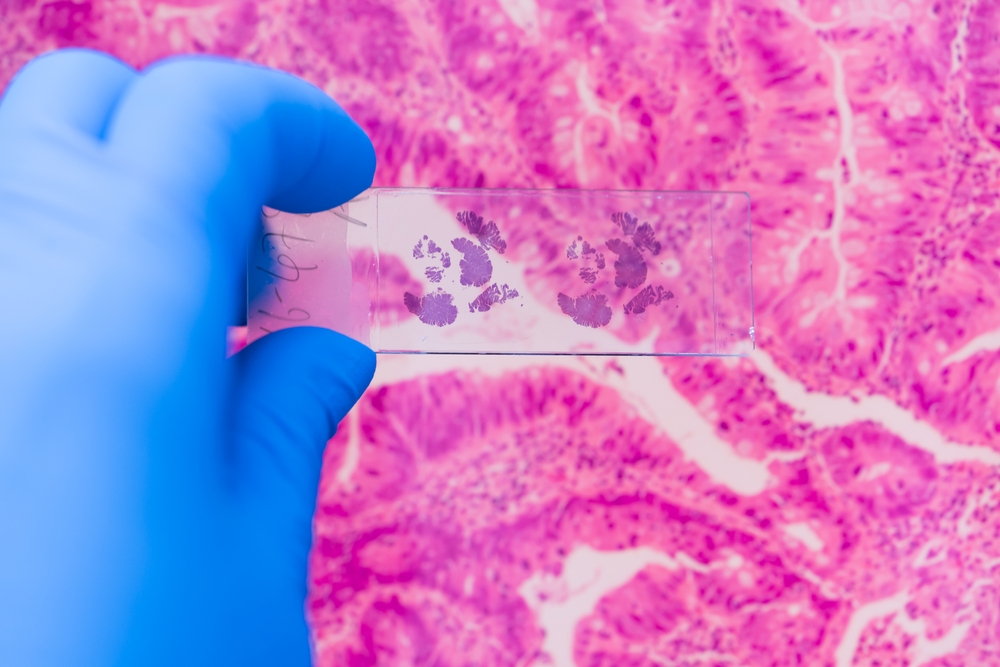

The story grew even more compelling when scientists transplanted CP-As from older mice into younger ones. Regardless of their environment, the aged cells retained their turbocharged ability to pump out fat. This revealed something profound: the change isn’t simply hormonal or lifestyle-driven. It’s programmed into the cells themselves, a kind of biological switch that flips on as we age. And when human fat tissue samples were analyzed, the same CP-As showed up in middle-aged people, confirming this isn’t just a mouse phenomenon it’s happening in us too.

The emergence of CP-As changes how we think about midlife weight gain. It’s not a simple matter of “eat less, move more.” At the cellular level, aging itself is reshaping our fat biology, programming the body to grow new fat cells right where they cause the most trouble: the belly.

How Scientists Figured It Out

Uncovering CP-As wasn’t a lucky accident. It took a combination of clever experiments, high-tech tools, and a willingness to challenge old assumptions. Scientists began with a simple question: do fat cells in middle age just grow larger, or are new ones actually being created?

To answer it, they used lineage-tracing mouse models, a technique that lets researchers tag existing fat cells with fluorescent markers. This allowed them to see, with startling clarity, that most of the belly fat cells in middle-aged mice weren’t old cells getting bigger they were brand new. More than 80 percent of visceral fat cells at that stage of life had been freshly generated.

Next came transplantation experiments that flipped conventional wisdom on its head. When fat stem cells from young mice were placed into older ones, they stayed mostly quiet, producing little new fat. But when stem cells from older mice were transplanted into young, healthy animals, those cells immediately churned out new fat. This proved the fat-making frenzy wasn’t triggered by environment or hormones it was encoded within the cells themselves.

The team then turned to single-cell RNA sequencing, a powerful genetic tool that maps which genes are active in individual cells. With this, they identified a previously unknown population of fat precursors: the CP-As. Unlike most stem cells that lose vigor with age, CP-As became more aggressive, multiplying and transforming at rates never seen in younger fat tissue.

Finally, to see if this was relevant to humans, the researchers analyzed fat tissue samples from people of different ages. The same CP-As appeared in middle-aged human tissue, showing the process wasn’t limited to rodents. Even in the lab, human CP-As displayed the same uncanny ability to produce new fat cells.

Together, these experiments built a watertight case: middle-age belly fat expansion is driven by a newly activated cellular program. The discovery doesn’t just explain a frustrating part of aging it offers a clear biological pathway that scientists might one day interrupt.

Why Belly Fat Matters for Health

It’s tempting to think of belly fat as just a cosmetic nuisance, but science tells a harsher truth: not all fat is created equal. The fat that collects just under the skin the stuff you can pinch isn’t nearly as dangerous as the fat that builds up deep inside the abdomen. This deeper layer, known as visceral fat, wraps around organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines. Far from being inert storage, visceral fat acts like a rogue organ of its own, releasing hormones and inflammatory chemicals that disrupt metabolism across the body.

The risks are sobering. Studies show that excess visceral fat is strongly linked to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease. It raises cholesterol, strains the liver, and contributes to systemic inflammation that accelerates biological aging. Research even connects belly fat to higher odds of certain cancers. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases warns that central obesity is a major driver of metabolic disease, independent of total body weight.

This explains why many people who don’t gain much overall weight in midlife still notice their health markers slipping. You can weigh the same at 45 as you did at 35 but carry that weight differently—less muscle, more belly fat and face greater health risks. As endocrinologist Qiong (Annabel) Wang, PhD, puts it, “People often lose muscle and gain body fat as they age even when their body weight remains the same.”

The discovery of CP-As reframes this danger. These cells don’t just pad the midsection for appearance’s sake they help fuel the very type of fat most damaging to health. Each new CP-A-generated fat cell in the belly adds to a system already primed for inflammation and imbalance. The belly bulge becomes more than a symbol of aging; it’s a biological signal of deeper processes that, left unchecked, can shorten both lifespan and healthspan.

A Potential Target for Prevention

The real breakthrough in this research isn’t just finding CP-As it’s discovering what drives them. Scientists traced their activity to a molecular switch called the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR). Think of LIFR as the ignition key: without it, CP-As don’t rev up into fat-making machines. With it, they multiply and expand visceral fat at alarming speed.

When researchers blocked this receptor in mice, the results were striking. Middle-aged animals that would normally pack on belly fat showed far less accumulation. The intervention didn’t wipe out normal fat function important for cushioning organs and storing energy but it stopped the runaway expansion of harmful visceral fat. In other words, turning off LIFR didn’t break the system; it calmed it down.

This makes LIFR a tantalizing target for future therapies. Imagine a treatment designed to quiet CP-As during midlife, preventing the cascade of new fat cells before they crowd the belly and stir up metabolic chaos. It could mark a shift in how we approach obesity and age-related disease: not just fighting the symptoms with lifestyle changes or after-the-fact medications, but addressing the root biological driver as it emerges.

Of course, the science is still in its early stages. Most of the work so far has been done in mice, and human data is limited. The initial tissue samples came mostly from men, meaning researchers still need to study women and broader populations. Age-related belly fat is influenced by many factors hormones, lifestyle, genetics and no single pathway will explain it all. Still, CP-As and their dependence on LIFR give scientists a concrete place to aim.

For the first time, the stubborn spread of midlife belly fat isn’t just a mystery of hormones or lifestyle. It’s a cellular program with a switch. And switches, unlike fate, can be flipped.

What You Can Do Now

Science may be working toward therapies that target CP-As directly, but you don’t have to wait for a pill or injection to defend your health. The biology of belly fat may be programmed, but how it plays out is still shaped by daily choices. Think of it as a tug-of-war between what aging cells want to do and how you support your body to resist.

- Keep moving: Regular physical activity not only burns calories it preserves muscle, which naturally declines with age. More muscle means a higher metabolism and less space for fat to take over. The CDC recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate activity per week, like brisk walking, cycling, or swimming, plus two days of strength training. These aren’t abstract numbers; they’re proven thresholds that reduce visceral fat and protect metabolic health.

- Prioritize strength training: Cardio keeps the heart strong, but lifting weights or even doing bodyweight exercises like squats and push-ups helps rebuild the lean tissue that aging steadily erodes. Every pound of muscle you keep is like a shield against fat gain and insulin resistance.

- Eat for resilience, not restriction: Diets that slash calories but starve muscle often backfire. Instead, focus on whole foods, especially lean proteins, vegetables, fruits, and fiber-rich carbs. Minimizing refined sugars and processed foods lowers the fat-storage signals amplified by visceral fat. A well-fed metabolism is a more stable one.

- Protect sleep and manage stress: Skimping on rest or carrying chronic stress keeps cortisol high a hormone notorious for promoting belly fat. Restorative sleep and simple stress-reducing practices like meditation, breathwork, or setting firmer boundaries are not luxuries; they are biological necessities if you want to control fat distribution.

- Stay consistent: The processes driving belly fat develop slowly, and so does change in the other direction. Crash programs rarely stick. What matters is steady, repeatable habits that add up over years. Small wins, multiplied daily, are more powerful than heroic bursts of discipline.

While CP-As and LIFR may someday be controlled in a lab or clinic, the levers you already have movement, food, recovery, consistency are potent tools to blunt their effects. The science shows belly fat has deep biological roots, but the daily practices that counter it are already within reach.

Turning Science Into Action

Midlife belly fat is not just about the way we look it’s a signal of how the body itself is changing with age. The discovery of CP-As and the LIFR pathway proves that aging runs deeper than wrinkles or gray hair; it reshapes our biology in ways we are only beginning to understand. That shift can feel daunting, but it also gives us power. When you know the mechanism, you can change the story.

Yes, part of belly fat is hardwired by time. But you are not powerless. Every choice to move, eat well, build muscle, rest deeply, and manage stress is a choice to push back against the biology that wants to tip the balance. And beyond personal health, these discoveries remind us of something bigger: science is rewriting the narrative of aging itself. What once looked inevitable can now be seen as changeable, maybe even preventable.

Your waistline, then, isn’t just a number or a frustration it’s a messenger. It’s telling you that your body is in transition. And now, with both science and daily action, you have the chance to meet that transition not with resignation, but with agency. The future of aging is not set in stone. It’s being built, cell by cell, habit by habit, choice by choice.

Loading...