Astronomers May Have Found the Earliest Supermassive Black Hole in the Universe

We spend a lot of our lives afraid of the dark. Not just the darkness of night, but the darkness inside uncertainty, struggle, and not knowing who we are becoming. We’re taught to believe that darkness means absence. Absence of hope. Absence of clarity. Absence of light.

But what if that belief is wrong? What if darkness is not empty at all, but active, alive, and shaping everything around it?

Recent discoveries using the James Webb Space Telescope are forcing scientists to rethink what they know about the darkest objects in the universe: black holes. And in doing so, they are offering us something more than astronomical insight. They are offering us a powerful mirror.

A Signal From the Heart of Our Galaxy

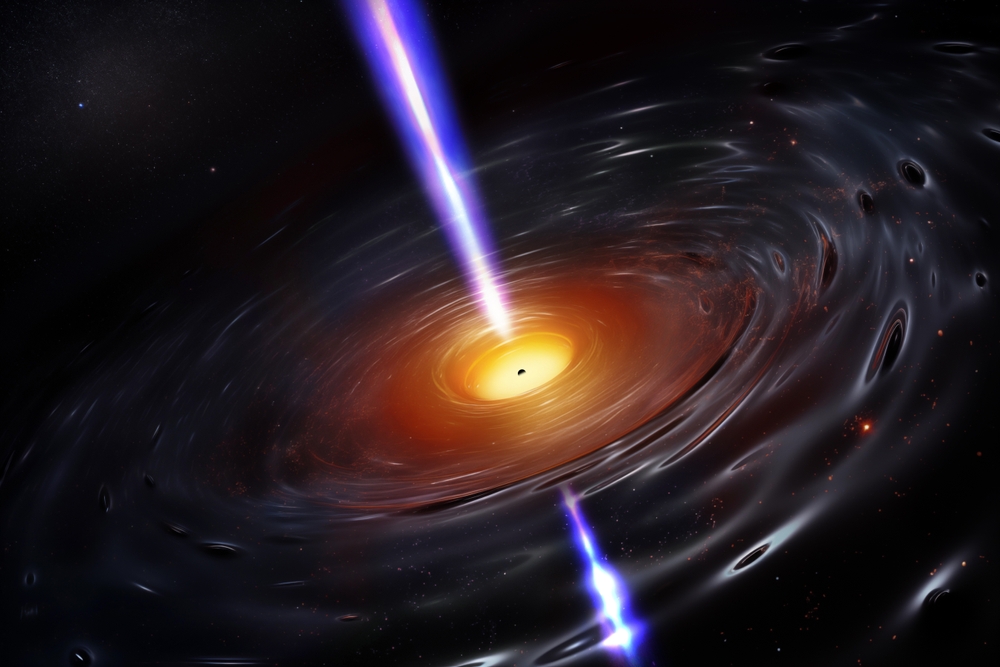

At the center of the Milky Way sits Sagittarius A*, a supermassive black hole with a mass equivalent to more than four million suns. It is the closest such object astronomers can study in detail, which makes it an essential reference point for understanding how black holes interact with their surroundings. While the black hole itself emits no light, the space around it is filled with gas, dust, and charged particles moving at extreme speeds, generating radiation before being pulled past the event horizon.

For years, astronomers observed flares from Sagittarius A* in near infrared and radio wavelengths, but those observations left a critical gap in the middle of the spectrum. The James Webb Space Telescope made it possible to observe these flares in the mid infrared for the first time, adding a missing layer to how scientists track the movement and evolution of energy around the black hole.

Sebastiano von Fellenberg of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy underscored the importance of this advance, saying, “The mid-infrared data is exciting, because, thanks to the new JWST data, we can close the gap between the radio and near infrared regimes, which had been a ‘gaping hole’ in the spectrum of Sgr A*.”

Beyond filling in the spectrum, the observations introduced a new level of precision. Researchers were able to observe Sagittarius A* simultaneously across four wavelengths using a single instrument, eliminating timing mismatches that can obscure how flares evolve. This allowed scientists to follow a single flare as a continuous physical process, tightening constraints on how quickly conditions near the black hole change and reducing uncertainty between competing interpretations of what drives this activity.

When Darkness Releases Energy

The flares observed from Sagittarius A* do not come from the black hole itself, but from the narrow region just outside the event horizon where matter is pushed to physical extremes. In this zone, gravity, motion, and electromagnetic forces compete in ways that cannot be recreated on Earth, allowing scientists to study fundamental physics under conditions that exist nowhere else.

Models described indicate that magnetic fields threading through this region play a central role. As superheated plasma swirls around the black hole, magnetic field lines can become twisted, stretched, and forced into contact. When those lines reconnect, stored magnetic energy is rapidly released into the surrounding particles, driving brief but powerful outbursts of radiation.

The James Webb observations made it possible to follow how this released energy evolves rather than treating each flare as a static event. By tracking changes in the flare’s spectral properties over time, researchers found evidence that the energized electrons lose energy as they emit radiation, a process known as synchrotron cooling. This provided direct insight into how quickly energy is dissipated in the environment surrounding Sagittarius A* and how tightly the flare’s brightness is linked to the motion of charged particles.

What emerges from this picture is not chaos, but order operating at an extreme scale. The flare is a measurable outcome of physical laws acting under immense pressure, revealing that even in regions defined by darkness, energy follows patterns that can be studied, modeled, and understood.

A Black Hole From the Dawn of Time

While one team of astronomers was studying the black hole at the center of our own galaxy, another group was looking much farther away. Much farther back.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers may have identified the most distant supermassive black hole ever observed, located in a galaxy known as GHZ2. The light from this galaxy has taken more than 13 billion years to reach us, meaning we are seeing it as it existed just 350 million years after the Big Bang.

Oscar Chavez Ortiz, a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas at Austin and lead author of the study, explained the significance of this finding, saying, “GHZ2 exists at a time when the universe was extremely young, leaving relatively little time for a supermassive black hole and its host galaxy to grow together.”

This discovery raises fundamental questions about how black holes form and grow. In the local universe, black holes and galaxies appear to evolve together over billions of years. But GHZ2 seems to challenge that timeline. How did something so massive appear so quickly in the universe’s history?

Rethinking How Giants Are Born

Astronomers currently debate two main possibilities for how early supermassive black holes form. One idea is that they begin as relatively small “light seeds” that somehow grow at extraordinary rates. The other is that they start as much larger “heavy seeds,” giving them a significant head start.

The evidence from GHZ2 is intriguing but not yet conclusive. The galaxy’s spectrum shows extremely intense emission lines, particularly from highly ionized atoms. Jorge Zavala, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and co-author of the study, described this observation, saying, “We are observing emission lines that require a lot of energy to be produced, known as high-ionization lines.”

One of the most important clues was the detection of a specific carbon emission line. Chavez Ortiz explained its significance clearly, stating, “Removing three electrons requires an extremely intense radiation field, which is very difficult to achieve with stars alone.”

That level of energy strongly suggests the presence of an actively feeding black hole, known as an active galactic nucleus. At the same time, GHZ2 lacks some of the usual indicators astronomers expect to see from such systems. This means the galaxy may be powered mostly by stars, or by a mix of stars and more exotic sources, including a young black hole.

The findings are still being tested, and the research has not yet been peer reviewed. Follow up observations with JWST and other instruments are planned to refine the data and confirm what is truly happening inside GHZ2.

What the Universe Keeps Reminding Us

There is a quiet lesson running through both of these discoveries. At the center of our galaxy, a black hole flares and cools, releasing energy in cycles we are only beginning to understand. At the edge of the observable universe, a possible supermassive black hole appears far earlier than our models predicted, forcing scientists to rethink how growth and evolution really work.

In both cases, certainty gives way to curiosity. Science advances not when we cling to what we think we know, but when we allow new evidence to stretch us beyond familiar frameworks. The James Webb Space Telescope was built for this purpose: to look deeper, not just into space, but into our assumptions. And this is where the story becomes personal.

When the Dark Places Shape Us

Many of us are taught to rush through darkness. To escape it. To fear it. But the universe does not seem to operate that way. Black holes grow in darkness. Galaxies evolve around them. Energy is stored, transformed, and released from regions where light itself cannot survive. Even the earliest structures in the cosmos may have formed faster and more creatively than our old models allowed.

The lesson is not that darkness is dangerous. The lesson is that darkness is powerful. Periods of uncertainty, grief, or inner struggle are often where the most fundamental changes occur. They are where assumptions break down. Where old identities collapse. Where something new begins to take shape, even if we cannot yet see it clearly.

Staying Curious Instead of Afraid

Astronomers do not treat these discoveries as threats to science. They treat them as invitations. An invitation to ask better questions. An invitation to refine old models. An invitation to listen more closely to what the universe is actually saying.

We can do the same in our own lives. When something unexpected appears, when growth seems to come too fast or too slow, when the darkness doesn’t behave the way we were told it should, the answer is not fear. The answer is curiosity. Because if the universe has taught us anything through the James Webb Space Telescope, it is this: even in the deepest darkness, there is structure. There is motion. There is meaning. And sometimes, the earliest light we discover is not out there among the stars, but forming quietly inside us, waiting for the moment it can finally be seen.

A Final Reflection

The story of black holes is no longer just a story about destruction or absence. It is a story about transformation, timing, and the courage to look where we once believed there was nothing to see.

As scientists continue to study Sagittarius A* and investigate the mysteries of GHZ2, they are not just mapping the universe. They are reminding us that growth does not always follow neat timelines, and that the unknown is not an enemy.

Sometimes, it is the very place where everything begins.

Featured Image from Shutterstock

Loading...