Gene Edited Immune Therapy Offers Hope Against Incurable Leukemia

For decades, some cancer diagnoses have carried an unspoken finality. Families are told that treatment options are exhausted, that medicine has done all it can, and that the focus must shift from cure to comfort. Few words are heavier than those. Yet, in hospital wards in London, a new chapter has begun to rewrite that ending for patients with one of the most aggressive and difficult blood cancers known to medicine.

A groundbreaking gene edited immune cell therapy called BE-CAR7 is offering something that once felt impossible for people with resistant T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Not just more time, but the possibility of clearing the disease entirely and rebuilding a healthy immune system. The results are already changing how scientists, doctors, and families think about what “incurable” really means.

This story is not only about a medical breakthrough. It is about children and adults who had run out of options, about a teenage girl who became the first person in the world to try an untested therapy, and about a new generation of cancer treatments that could transform care far beyond a single disease.

A Blood Cancer With Limited Options

T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, often shortened to T-ALL, is a fast growing cancer that affects white blood cells known as T cells. These cells normally play a crucial role in defending the body against infection. When they become cancerous, they multiply uncontrollably and crowd out healthy blood cells in the bone marrow.

Modern chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants have dramatically improved survival for many children with leukemia. Most patients with T-ALL respond well to standard treatment and go on to live full lives. But around one in five patients do not. For these children and adults, the cancer resists chemotherapy, returns after transplant, or progresses so aggressively that treatment cannot keep pace.

For families in this situation, the experience is devastating. The disease often returns stronger and faster with each relapse. Doctors must balance increasingly harsh treatments against the toll they take on the body. Eventually, the conversation shifts toward experimental options or end of life care. Until recently, there was no proven therapy designed specifically for T cell leukemia that had stopped responding to everything else.

Why T Cell Leukemia is So Hard to Treat

Immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer care in recent years. One of the most powerful tools is CAR T cell therapy, which reprograms a patient’s own immune cells to hunt down and destroy cancer. This approach has shown remarkable success in certain B cell leukemias and lymphomas.

T cell leukemia presents a unique problem. The cancer itself arises from T cells, the very cells doctors rely on to build CAR T treatments. When scientists design immune cells to target T cells, the therapy risks attacking itself. This self destruction, often called friendly fire, makes traditional CAR T approaches ineffective or impossible.

For years, researchers understood what needed to be done but lacked the tools to do it safely. They needed a way to engineer immune cells that could kill cancerous T cells without wiping themselves out or causing catastrophic damage to the patient’s immune system.

Enter Base Editing and BE-CAR7

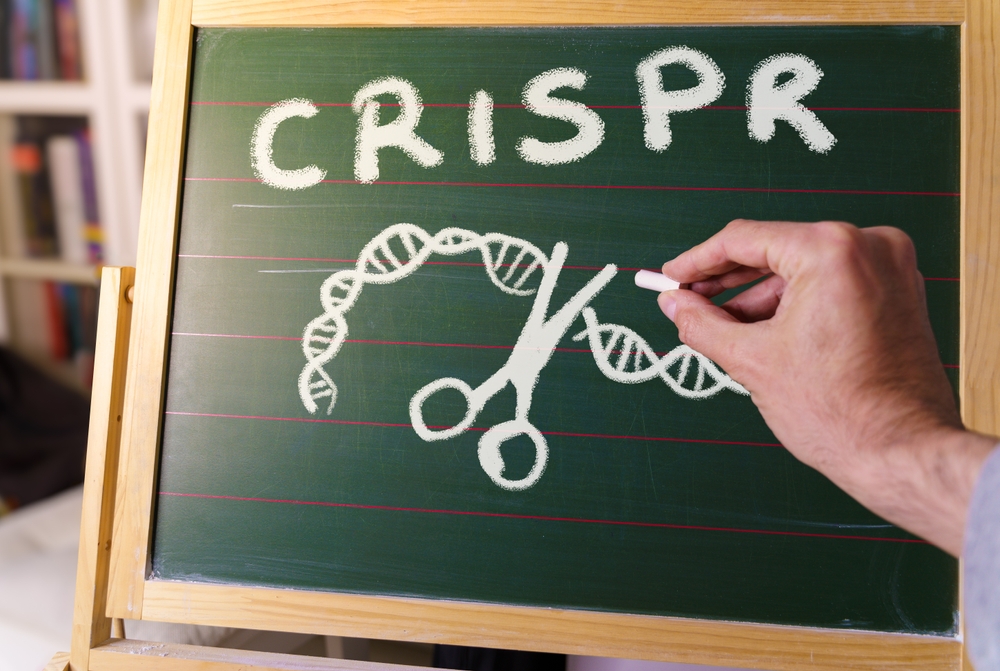

The turning point came with the development of base editing, a highly precise form of gene editing related to CRISPR technology. Instead of cutting DNA strands, base editing allows scientists to change single letters of genetic code. This reduces the risk of unintended damage and makes complex edits possible within living cells.

Using this technology, researchers developed BE-CAR7. It is a new type of CAR T cell therapy built from healthy donor immune cells rather than from the patient. These donor cells are edited in multiple ways so they can be used safely in anyone who needs them.

Several key genetic changes make BE-CAR7 possible:

First, scientists remove the natural T cell receptor from donor cells. This prevents the patient’s immune system from recognizing the donor cells as foreign and attacking them.

Second, they remove identifying markers that would normally cause donor cells to be rejected. This step turns the cells into what researchers call universal cells, meaning they can be prepared in advance and given to different patients without matching.

Third, they delete the CD7 marker from the donor cells. CD7 is found on both healthy and cancerous T cells. Without removing it, the engineered cells would destroy each other.

Finally, researchers add a new chimeric antigen receptor that targets CD7 on cancerous T cells. This gives the edited cells a single purpose: seek out and destroy leukemia.

The result is an immune cell that has been carefully redesigned at the genetic level to do something nature never intended.

From Laboratory Theory to Hospital Reality

In 2022, the BE-CAR7 concept moved from theory into clinical reality. Doctors at Great Ormond Street Hospital and University College London treated a 13 year old girl named Alyssa, who had exhausted all standard options. Chemotherapy had failed. A bone marrow transplant had failed. Palliative care was being discussed.

Alyssa became the first person in the world to receive a base edited CAR T cell therapy.

The process was intense. Her immune system was first suppressed with chemotherapy to make room for the edited cells. Then BE-CAR7 cells were infused into her bloodstream. Over the following weeks, the engineered cells multiplied and began eliminating T cells throughout her body, including the leukemia driving her disease.

Within weeks, tests could no longer detect leukemia. Alyssa went on to receive a bone marrow transplant to rebuild a healthy immune system. Today, years later, she remains cancer free and off treatment.

Her recovery was not a promise. It was a question. Would this result hold in other patients?

What the New Trial Results Show

Since that first treatment, eight more children and two adults with resistant T-ALL have received BE-CAR7 at hospitals in London. All had disease that had stopped responding to conventional therapies.

The results, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, are striking.

More than 80 percent of patients achieved deep remission. This means no detectable cancer using the most sensitive tests available. These remissions were strong enough to allow patients to proceed to a stem cell transplant, which offers the best chance for long term survival.

Nearly two thirds of patients remain disease free so far. Some have now passed the three year mark without relapse, a milestone that once seemed unreachable for this group.

Side effects were serious but manageable. Patients experienced low blood counts, skin rashes, and immune reactions such as cytokine release syndrome. The greatest risk came from infections during the period when T cells were temporarily wiped out. Doctors emphasize that these treatments are demanding and require highly specialized care.

Still, for patients who previously had no viable options, the balance has shifted.

Universal Cells and Why They Matter

One of the most important features of BE-CAR7 is that it does not rely on harvesting cells from the patient. Traditional CAR T therapies require collecting a patient’s own immune cells, modifying them, and then returning them weeks later. For aggressive cancers, that delay can be deadly.

Because BE-CAR7 cells are made from healthy donors and stored in advance, they can be given quickly when a patient needs them. This off the shelf approach could make advanced immunotherapy more accessible and potentially less expensive in the future.

It also opens the door to treating patients whose immune systems are too damaged to provide usable cells of their own.

The Human Side of Experimental Medicine

Behind every percentage point in a clinical trial is a family navigating fear, hope, and uncertainty. Doctors involved in the BE-CAR7 study have been clear that while the results are encouraging, they are also mindful of those for whom the treatment did not work as hoped.

These therapies are not gentle. They demand long hospital stays, careful monitoring, and enormous emotional resilience from patients and caregivers alike. Researchers stress that progress comes from learning from every outcome, including setbacks.

Alyssa herself has spoken about her decision to join the trial. She knew there were no guarantees. She chose to proceed not only for herself, but in the hope that it might help others facing the same diagnosis in the future.

Today, she is back at school, spending time with friends, learning to drive, and dreaming of becoming a research scientist. Her life now looks like one she once thought she might never have.

The Human Side of Experimental Medicine

BE-CAR7 represents more than a single treatment for a rare leukemia. It demonstrates the power of precision gene editing to solve problems that once seemed insurmountable.

Scientists are already exploring whether similar strategies could be used against other cancers that arise from immune cells. The concept of universal, pre prepared immune therapies could transform how quickly and effectively doctors respond to aggressive disease.

There are still many questions to answer. Larger trials are needed. Long term risks must be carefully tracked. Access and cost will remain challenges. But the foundation has been laid.

A Cautious but Powerful Hope

For families facing resistant T cell leukemia, hope has often felt fragile. BE-CAR7 does not erase the difficulty of the disease or the intensity of its treatment. What it offers is something just as meaningful: a real chance where there was none before.

In medicine, breakthroughs are rarely single moments. They are built through years of research, collaboration, and courage from patients willing to step into the unknown. BE-CAR7 stands as a reminder that even in the most difficult cases, innovation can open doors that once seemed permanently closed.

For now, the word incurable no longer carries the same weight it once did. And for some patients, that change means everything.

Loading...