Cleaning linked to long-term lung damage comparable to smoking, study reveals

We live in a world obsessed with cleanliness. Sparkling windows, lemon-scented kitchens, spotless bathrooms – these have become symbols of order, responsibility, even love. To clean is to care. Yet beneath this glossy picture, there is an unsettling paradox. The very act that promises to protect our health may be slowly chipping away at it. Imagine spraying chemicals to wipe away grime, believing you are making your family safer, when in truth, you are inhaling invisible enemies. These particles travel deep into the lungs, lodging themselves in the tissues that give us life. What seems like care could, over years, become harm.

The University of Bergen in Norway uncovered this hidden danger. They followed more than 6,000 people over a span of two decades. Their results were not whispers or rumors but clear data: women who cleaned regularly, whether in their own homes or professionally, experienced a decline in lung function equivalent to smoking 20 cigarettes every single day for 20 years. Alongside this, their risk of asthma was about 40% higher than those who avoided frequent exposure. This is not a trivial statistic. This is a wake-up call. It tells us that our pursuit of spotless rooms may come with an unseen price – our very breath.

A Heavy Price for Clean Homes

To understand the depth of this impact, picture lung function as the rhythm of life itself. Doctors often measure it using FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in one second. It tells us how much air can be expelled in a quick, strong breath. For those consistently exposed to cleaning sprays, this number declined much faster than in people who avoided them. Over years, the decline is not just a medical report. It’s a mother struggling to climb stairs, a worker finding themselves winded on the walk home, a grandparent unable to play freely with their grandchild. Every number carries a human story.

What stands out is that this injury is not equal across the board. Women bore the brunt, not because they were weaker, but because they shouldered more of the cleaning duties, both at home and at work. In the 1990s, when the study began, women were statistically far more likely to be using sprays daily. Their exposure was consistent, relentless, and prolonged. Men, who did not clean as often, showed little to no measurable decline. This reveals how social expectations and roles can shape health outcomes in ways we rarely acknowledge. The burden of maintaining clean homes was silently etched into women’s lungs.

This isn’t about assigning blame to individuals but about revealing the larger system at play. We live in a culture that rewards surfaces that shine, but rarely pauses to question what keeps the air itself clean. When we look at the numbers from this study, we are not just learning about chemicals and lungs; we are learning about invisible labor, about societal pressures, and about the cost of neglecting what can’t be seen. Cleanliness may offer pride and respectability, but at what cost if it’s measured in breaths lost too soon?

Why Does It Happen?

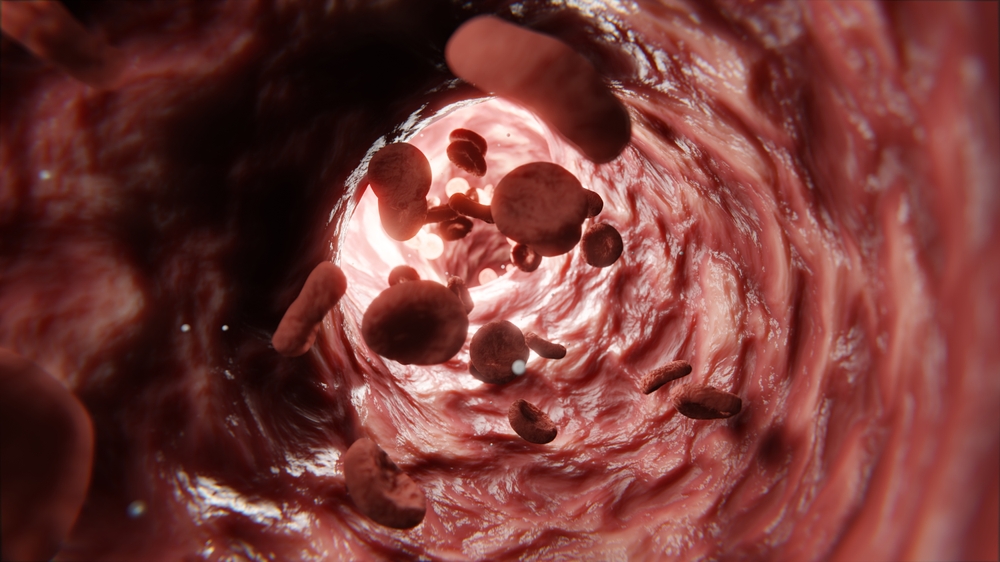

The question at the heart of this discovery is simple: why are cleaning products so destructive to lungs? The answer lies in how these products behave once released. Cleaning sprays, by design, break into fine particles to cover surfaces quickly and evenly. But what covers the counter also fills the air. Those particles drift, invisible but potent, entering deep into the respiratory system. Unlike dust that our noses can filter out, these aerosols reach the alveoli, the tiny sacs where oxygen enters the blood. Over time, repeated exposure inflames, scars, and weakens these delicate tissues.

The ingredients themselves make the problem worse. Ammonia, bleach, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are common in many household cleaners. Each has a role in dissolving stains and killing germs, but each is also an irritant. When they meet the sensitive lining of the lungs, they cause irritation that may feel minor in the moment – a slight cough, a sting in the nose, a watery eye. But the body doesn’t forget. Inflammation becomes chronic when it never has time to fully heal. Just as tobacco smoke leaves behind traces of damage with every puff, cleaning sprays leave behind reminders with every use.

Sprays are especially harmful because of their mode of application. A liquid cleaner poured into a bucket may release fewer chemicals into the air, but a spray transforms into mist, impossible to avoid inhaling. Even if you hold your breath while spraying, the particles remain suspended long after you exhale again. This persistence turns routine cleaning into long-term exposure. And because these products are marketed as harmless household tools, most people never realize they are taking in something as damaging as smoke. The insidiousness of this harm is what makes it so dangerous.

What This Means for You, Me, Us

It is easy to dismiss these findings as something that happens only to professionals or people with extreme exposure. But the study shows otherwise: even regular household cleaning, done once or twice a week over many years, can lead to measurable lung decline. This matters because cleaning is not optional. Every person wants a safe, healthy home. Yet when the very act of keeping that space safe chips away at our long-term health, the contradiction cannot be ignored.

For those who clean professionally, the stakes are even higher. Every workday becomes a gamble with their lungs, a trade of health for wages. The damage is not always immediate. It creeps in over years, often unnoticed until breathlessness becomes a constant companion. By then, the loss is permanent. And unlike smoking, where people make a personal choice, cleaning is often a duty – a job, a role, or an expectation. The lack of choice makes the risk even more unjust.

There is also the ripple effect on families. Children and the elderly are particularly sensitive to air quality. If cleaning chemicals linger, they are inhaled by everyone who shares the space. This means the burden of harm extends beyond the person holding the spray bottle. It is carried by those who never agreed to inhale these toxins. When seen in this light, cleaning becomes not just a personal issue but a public health concern. It calls us to rethink what it truly means to create safe, nurturing environments.

Real Change — What You Can Do Starting Today

The most empowering message from this research is that change is possible. Knowledge is not meant to frighten but to liberate. If cleaning sprays and harsh chemicals are as harmful as smoking, then every small choice we make to reduce their use is like putting out a cigarette before it burns us further. The first step is to question what we’ve been taught: do we really need strong fragrances and harsh solutions for every task? Or have we been sold an illusion of “freshness” that hides a darker truth?

Gentler methods often work just as well. Soap, water, and microfiber cloths can remove dirt effectively without polluting the air. Many households have rediscovered these basics and found them not only safer but cheaper. Ventilation is another powerful ally. Something as simple as opening a window while cleaning can transform the environment, flushing out chemicals before they settle in your lungs. These steps may feel small, but repeated over years, they preserve the most precious gift we have: the ability to breathe freely.

For professionals, stronger measures are essential. Masks designed for fine particles, safer cleaning products, and regulations that protect workers’ health are not luxuries – they are necessities. Employers and governments must recognize that exposure to cleaning chemicals is an occupational hazard, no different from working in a factory with fumes. The University of Bergen researchers themselves stressed the importance of seeing cleaning as a public health issue. By amplifying their call, we can push for change that protects millions worldwide.

What Do We Value?

When we step back, this story becomes less about chemicals and more about values. What do we value more: the illusion of a spotless surface or the reality of healthy lungs? We’ve been taught that a “good” home is one that smells like lemon polish and bleach. Yet what if a truly good home is one that lets us breathe deeply, without pain, without risk? The shine of a countertop fades quickly, but the strength of a healthy body lasts a lifetime. Perhaps our priorities need adjusting.

Imagine a world where companies compete not on how white their detergents can make a shirt but on how safe their products are for our lungs. Imagine children learning that cleanliness includes the quality of the air they breathe. These shifts would redefine what it means to care for a home. It would mean aligning our habits with both hygiene and health, rather than choosing one over the other.

Ultimately, we all want the same thing: to live in spaces that feel safe and nurturing. True safety doesn’t come from hiding germs alone but from protecting the people who live in those spaces. When we understand this, we begin to see that the cleanest home is not the one that sparkles the most, but the one that allows every person inside to take a full, unbroken breath.

Featured Image via Shutterstock.com

Loading...