Depression May Begin in the Immune System

For decades, depression has been framed almost exclusively as a disorder of the brain. Chemical imbalances, faulty neurotransmitters, and dysfunctional neural circuits have dominated both public understanding and medical treatment. While this framework has helped millions, it has also left a significant number of people without relief. Many patients do not respond to antidepressants, and others experience only partial improvement despite years of treatment. As rates of depression continue to rise worldwide, scientists are being forced to ask a deeper question: what if depression is not only a brain disorder at all?

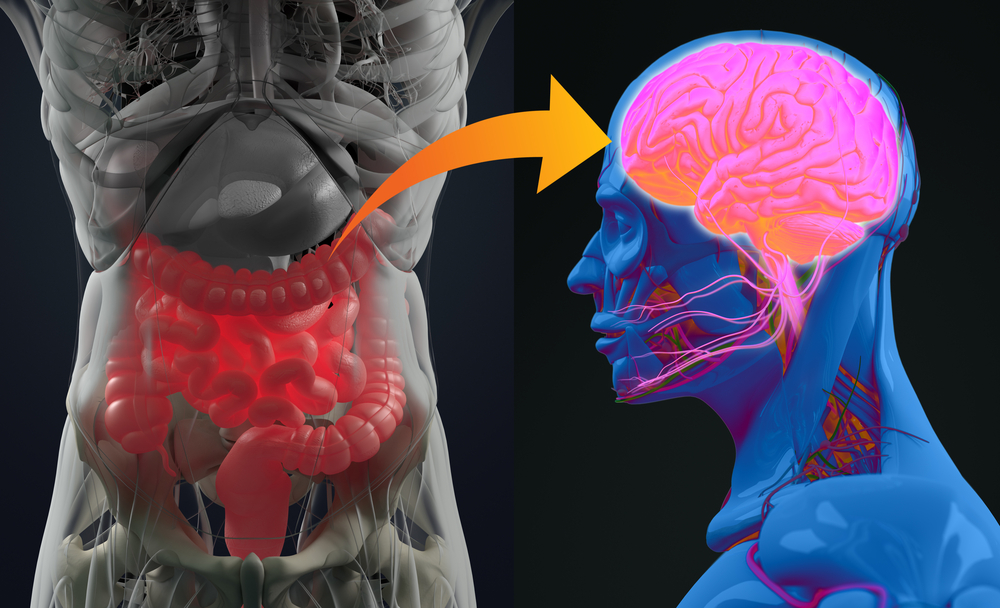

Over the past two decades, a growing body of research has pointed toward a surprising and transformative insight. The immune system, particularly chronic inflammation, appears to play a central role in shaping mood, motivation, and emotional resilience. Instead of being confined to thoughts or neurotransmitters alone, depression may emerge from a complex interaction between immune signaling, stress, gut health, and the brain’s protective barriers.

This emerging perspective does not invalidate psychology or neuroscience. Rather, it expands them. It reframes depression as a whole body condition in which the brain, immune system, and environment are constantly communicating. In this view, depression may represent a prolonged biological stress response that never fully resolves, quietly reshaping brain function over time.

The Immune System’s Hidden Role in Mood

The immune system exists to protect the body. When an infection or injury occurs, immune cells release signaling molecules called cytokines that coordinate inflammation, recruit white blood cells, and promote healing. This response is essential for survival. Under normal circumstances, inflammation rises, does its job, and then subsides.

Problems arise when inflammation becomes chronic. Low-grade immune activation can persist long after the original trigger is gone. Instead of healing, inflammatory signals continue to circulate through the bloodstream, subtly altering biological systems that were never designed to remain inflamed indefinitely.

Large-scale studies have consistently found that people with major depressive disorder often show elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein. These biomarkers are not produced by the brain itself. They are generated by immune cells throughout the body. Their presence suggests that depression is often accompanied by an activated innate immune response.

What makes this connection especially compelling is that inflammation does not merely coexist with depression. In experimental settings, administering immune cytokines to humans or animals reliably induces behaviors that closely resemble depressive symptoms. Fatigue, loss of motivation, social withdrawal, sleep disruption, and slowed cognition are all hallmarks of what researchers call sickness behavior. These changes evolved to conserve energy during illness, but when inflammation becomes chronic, sickness behavior can quietly transform into depression.

When the Brain’s Border Is Breached

For many years, scientists believed the brain was largely isolated from immune activity by the blood-brain barrier. This tightly regulated layer of endothelial cells acts as a selective border, allowing nutrients and hormones to pass through while blocking potentially harmful substances.

Recent discoveries have reshaped this assumption. The blood-brain barrier is not an impenetrable wall. It is a dynamic interface that responds to signals from the immune system. Chronic inflammation can weaken its structural integrity, making it more permeable than it should be.

Research led by neuroscientist Caroline Ménard at Université Laval demonstrated how chronic social stress can physically damage the blood-brain barrier in animal models. Mice exposed to repeated social defeat developed elevated inflammatory cytokines in their blood. When researchers examined their brains, they observed microscopic gaps in the blood-brain barrier that were absent in resilient mice.

These gaps allowed immune signals to cross into the brain more easily, triggering neuroinflammation and altering neural circuits involved in mood and motivation. Similar structural damage has since been identified in postmortem brain tissue from people with depression who died by suicide, suggesting that this mechanism is not limited to animal models.

Once the blood-brain barrier becomes compromised, immune molecules that normally operate in the body can enter the brain environment. There, they activate microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, setting off a localized inflammatory response that can persist for years.

How Inflammation Alters Brain Chemistry

Inflammatory cytokines exert powerful effects on neurotransmitters that regulate mood. Serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine are especially vulnerable to immune signaling.

One of the most studied pathways involves the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. When activated by inflammation, this enzyme diverts tryptophan away from serotonin production and toward the kynurenine pathway. This reduces serotonin availability while generating metabolites that can be neurotoxic in excess.

Inflammation also increases the activity of neurotransmitter transporters, pulling serotonin and dopamine out of synapses more rapidly. The combined effect is a reduction in signaling within reward and motivation circuits, even when neurotransmitters are being produced normally.

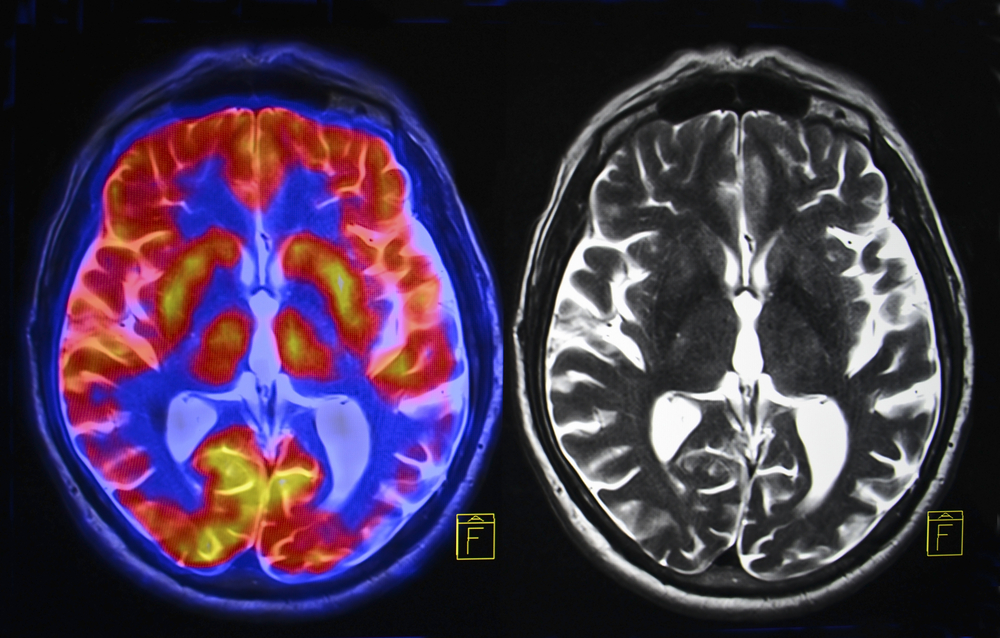

Dopamine is particularly affected in regions like the basal ganglia, which play a key role in motivation and effort. Imaging studies have shown that inflammatory states reduce dopamine signaling in these regions, closely mirroring the anhedonia and fatigue commonly reported in depression.

These biochemical changes are not abstract. They directly shape how the brain processes reward, effort, and emotional meaning. When immune signals dominate, the brain shifts into an energy-conserving mode that prioritizes survival over pleasure or exploration.

Stress as an Immune Trigger

Psychological stress has long been recognized as a major risk factor for depression. What is now becoming clear is that stress exerts much of its damage through immune activation.

Experiments using the Trier Social Stress Test, a standardized public speaking challenge, have shown that even brief social stress can rapidly activate inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB. Within minutes, immune genes are switched on, preparing the body for injury or infection even when no physical threat exists.

Chronic stress magnifies this effect. Individuals exposed to early life adversity show exaggerated inflammatory responses to stress decades later. Elevated cytokine levels persist long after the stressful event has ended, embedding vulnerability into the immune system itself.

Stress also disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates cortisol release. Inflammation interferes with glucocorticoid receptor function, reducing the body’s ability to shut down stress responses efficiently. The result is a feedback loop in which stress fuels inflammation, and inflammation sustains stress biology.

Over time, this loop can reshape brain circuits responsible for emotion regulation, attention, and resilience.

Microglia and the Brain’s Immune Memory

Microglia are specialized immune cells that reside permanently in the brain. Their role is to monitor neural tissue, clear debris, and respond to threats. Under chronic inflammatory conditions, microglia can become overactivated.

Groundbreaking research from McGill University and the Douglas Institute, published in Nature Genetics, identified specific subtypes of microglia that show altered gene expression in people with depression. These immune cells displayed changes linked to inflammation, synaptic pruning, and neural signaling.

This finding is significant because microglia directly influence how neural connections are formed and maintained. When overactive, they may prune synapses excessively, weakening circuits involved in mood regulation and cognitive flexibility.

The study also identified disruptions in excitatory neurons that interact closely with stress and emotion processing. Together, these cellular changes provide concrete biological evidence that depression involves immune-mediated remodeling of brain networks.

The Gut, Immunity, and Emotional Resilience

The immune system does not operate in isolation. One of its most active interfaces with the environment is the gut. The intestinal lining contains a dense network of immune cells constantly interacting with the microbiome.

Research from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine has revealed that a specific class of immune cells called gamma delta T cells plays a critical role in stress-induced depression. In mouse models, chronic stress increased these immune cells in the gut, altered the microbiome, and led to social avoidance behaviors.

Stress-susceptible mice showed reduced levels of Lactobacillus johnsonii, a beneficial bacterium associated with immune regulation. Restoring this bacterium normalized immune activity and improved behavior, suggesting that gut microbes can directly influence emotional resilience through immune pathways.

Human studies support this link. Individuals with major depressive disorder often show altered gut microbiota composition, with lower levels of beneficial Lactobacillus species correlating with more severe symptoms.

These findings reinforce the idea that depression can originate far from the brain itself, emerging from immune dysregulation in the gut that eventually reshapes neural signaling.

Why Some People Are More Vulnerable

Not everyone with inflammation becomes depressed. This variability has led researchers to investigate vulnerability factors that determine who develops symptoms.

Genetic differences in immune signaling, blood-brain barrier integrity, and stress hormone regulation appear to play a role. Some individuals may have inherently more permeable brain barriers or heightened immune sensitivity, making them more susceptible to inflammatory signals.

Sex differences have also been observed. In men, blood-brain barrier disruptions often appear in reward-related regions like the nucleus accumbens. In women, damage is more frequently observed in the prefrontal cortex, which governs self-perception and social cognition. These patterns may help explain why depression manifests differently across genders.

Early life experiences further shape immune programming. Childhood adversity can leave lasting marks on immune cells, biasing them toward heightened inflammatory responses later in life. This immune memory may silently increase vulnerability to depression decades after the original stress has passed.

Rethinking Treatment Through an Immune Lens

Traditional antidepressants primarily target neurotransmitters. While effective for many, they do not directly address inflammation. Research now suggests that elevated inflammatory markers predict poorer response to conventional treatments.

This has sparked growing interest in anti-inflammatory approaches to depression. Some antidepressants already reduce cytokine levels indirectly, but more targeted strategies are being explored.

Clinical trials have shown that anti-inflammatory agents such as celecoxib can enhance antidepressant response in certain patients. Biological therapies that block cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha have reduced depressive symptoms in people with autoimmune diseases, independent of improvements in physical illness.

Newer treatments are investigating interleukin-6 blockers such as tocilizumab for inflammation-associated depression. These approaches aim to identify specific subtypes of depression driven by immune dysregulation rather than applying a one-size-fits-all model.

Beyond pharmaceuticals, lifestyle interventions that reduce inflammation are gaining scientific support. Regular physical activity, adequate sleep, stress reduction, and diets rich in anti-inflammatory nutrients all influence immune signaling. Emerging research on vagus nerve stimulation highlights the role of the parasympathetic nervous system in dampening inflammation and restoring balance.

A Broader View of Healing

The immune model of depression does more than explain treatment resistance. It reshapes how we understand emotional suffering itself.

From this perspective, depression may represent a body that has been signaling distress for too long. Inflammation, once meant to protect, becomes a chronic alarm that never shuts off. The brain adapts by conserving energy, narrowing focus, and withdrawing from stimulation.

Seen this way, depression is not a failure of will or a flaw of character. It is a biological adaptation pushed beyond its useful limits by modern stress, trauma, and environmental pressures.

This understanding invites a more compassionate approach to mental health. It encourages treatments that address the whole system rather than isolating the mind from the body.

Healing the Signal, Not Just the Symptom

The emerging science is clear. Depression cannot be fully understood by looking at the brain alone. Immune activation, inflammation, stress biology, and gut health are woven into the condition at every level.

As research continues to uncover the immune roots of depression, a more nuanced picture is coming into focus. One that honors both the biological complexity of the human body and the lived experience of emotional pain.

Healing, in this context, becomes less about correcting a single chemical imbalance and more about restoring balance across interconnected systems. By calming inflammation, supporting immune resilience, and addressing the deeper physiological imprints of stress, it may be possible to help the brain remember how to feel safe, motivated, and alive again.

Depression, it turns out, may not just be in the mind. It may be the body asking, quietly and persistently, to be heard.

Loading...