Harvard Scientist Claims ‘Hostile’ Object Coming at Us Is Advanced ‘Mothership’ and Issues Warning

Something is moving through our solar system. It doesn’t follow the usual rules. It travels faster than gravity should allow, glows in the wrong direction, and may be watching more than just stars. Some call it a comet. Others call it something else. What if the truth isn’t just out there—but inside the way we see?

When Science Sounds Like a Whisper from the Stars

For as long as we’ve existed, we’ve looked up at the night sky and wondered what waits beyond it. Some cultures saw gods, others saw maps of destiny. Today, through the lens of powerful telescopes, we see something else—mysteries that don’t fit the script we’ve written for the cosmos.

On July 1, 2025, astronomers spotted a faint speck hurtling through space, a visitor from beyond our solar system. They named it 3I/ATLAS. At first glance, it seemed like an ordinary comet, a frozen wanderer making its brief appearance before fading into history. But as researchers measured its speed—130,000 miles per hour—and traced its unusual trajectory, doubts began to rise. It wasn’t just fast. It wasn’t just strange. It was different.

That difference set off one of the most controversial claims in modern astronomy. Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb suggested that this interstellar object might not be a natural comet at all. In a paper, Loeb and his colleagues proposed it could be an advanced alien “mothership”, possibly even hostile.

Loeb and his colleagues also wrote in their study: “The consequences, should the hypothesis turn out to be correct, could potentially be dire for humanity.” However, not all experts agree. Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina, dismissed the theory, saying: “All evidence points to this being an ordinary comet that was ejected from another solar system, just as countless billions of comets have been ejected from our own solar system.”

For many scientists, this suggestion bordered on science fiction. Astronomers from NASA and the University of Regina argued that all evidence still points to 3I/ATLAS being a comet, ejecting ice and dust as it’s warmed by the Sun. Peer-reviewed studies support this, showing clear cometary signatures in its coma and rotation. Even Loeb admits that his theory is unlikely, conceding that:

“By far, the most likely outcome will be that 3I/ATLAS is a completely natural interstellar object, probably a comet.”

But Loeb’s words still linger, because they point to something deeper than astrophysics. They touch the nerve that has always existed in us: fear of the unknown, hunger for contact, and the human habit of projecting our own anxieties onto the heavens.

This is not about proving whether 3I/ATLAS is a comet or a craft. It is about something bigger: how we wrestle with mystery, how science holds space for both skepticism and imagination, and what this visitor—whatever it turns out to be—says about us.

The Visitor and the Voices

Shortly after its detection, the interstellar object now known as 3I/ATLAS sparked a theory that challenged scientific orthodoxy. A technical report authored by Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, along with Adam Hibberd and Adam Crowl, proposed a testable hypothesis: 3I/ATLAS may not be a comet at all, but rather an advanced extraterrestrial spacecraft. The paper, which appeared on arXiv, did not claim certainty but argued that the object’s rare combination of orbital characteristics deserved exploration beyond conventional models.

They noted a statistically improbable alignment—close approaches to Venus, Mars, and Jupiter—that, when taken together, raised the possibility of intentional navigation. While the authors referred to the work as a “pedagogical exercise,” they warned of high-impact implications: “The consequences, should the hypothesis turn out to be correct, could potentially be dire for humanity.”

In a related blog post expanding on the theory, Loeb suggested that the object’s positioning behind the Sun during its perihelion could allow it to avoid detailed observation and potentially deploy “gadgets” toward Earth or neighboring planets. He wrote that this timing “offers various benefits to an extraterrestrial intelligence,” such as conducting surveillance or redirection maneuvers unseen by Earth-based instruments.

These propositions were met with immediate and forceful rejection from much of the astronomical community. Chris Lintott, astrophysicist at the University of Oxford, publicly criticized Loeb’s claims as “nonsense on stilts,” expressing concern that such ideas undermined serious research into interstellar objects. Other experts, while advocating for open inquiry, emphasized the need for empirical grounding rather than inference drawn from statistical anomaly.

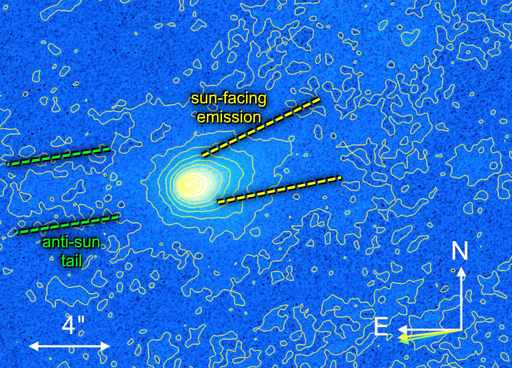

Meanwhile, recent imaging from the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories provided support for a more conventional interpretation. Observational data published by NASA showed a diffuse coma—a surrounding cloud of dust and gas—consistent with behavior expected from a natural interstellar comet. Additional spectral analysis published via arXiv detected hydroxyl emissions, a typical sign of water sublimation from icy nuclei.

While Loeb’s theory remains controversial, it has reignited an enduring question in science: how far should researchers go when interpreting outliers? The 3I/ATLAS paper did not claim proof—it invited testing. For critics, that invitation overstepped credibility. For others, it reflected what science sometimes forgets in its search for certainty: the possibility that the universe is stranger than even our best instruments can predict.

The Mind and the Method

When a mysterious object like 3I ATLAS enters our solar system, it does more than draw curiosity. It triggers something fundamental in us. Our minds instinctively search for clarity when facts are still incomplete. Behavioral scientists call this ambiguity aversion. We are hardwired to prefer clear outcomes over uncertain ones. In controlled experiments, participants routinely avoid decisions that involve unknown variables, even if the actual risk is lower. One study confirmed this bias, showing that people tend to perceive ambiguous options as more threatening, even when evidence is neutral or missing.

Culture magnifies this instinct. Modern storytelling, especially through film and media, has conditioned us to expect that any encounter with the unknown—especially in space—must come with an agenda. Our collective imagination is rich with narratives of invasions, surveillance, and advanced intelligence hidden just out of sight. So when a respected astrophysicist offers a scenario involving extraterrestrial technology, the reaction is not purely scientific. It taps into ideas already seeded in the public consciousness.

But while emotion may start the conversation, science is meant to shape how we finish it. Throughout history, ideas that once sounded outlandish—like the existence of unseen planets, plate tectonics, or microbial life from space—were only accepted after they passed the tests of evidence. That testing is what separates science from speculation. It is not wrong to wonder. It is only dangerous when we stop verifying.

Avi Loeb and his co-authors described their approach to 3I ATLAS as exploratory, not declarative. In their technical study, they framed it as a thought experiment—an exercise in asking whether known anomalies could fit an artificial origin if tested with rigorous tools. Whether or not the hypothesis stands up to data is secondary to the fact that they made it falsifiable. That is the cornerstone of scientific method. Not proof by imagination, but possibility filtered through precision.

Speculation is not the enemy of science. But science requires that every imaginative leap returns to ground. The history of discovery shows us that progress happens when creativity and skepticism move together. Without imagination, we stop asking bold questions. Without skepticism, we forget which answers are real.

Maybe 3I ATLAS is just a frozen traveler from far away. Or maybe it is something we have not yet learned to categorize. Either way, its value is not only in what it is—but in how it challenges us to remain awake. To remember that in science, as in life, we must learn to walk the fine line between openness and doubt, wonder and reason.

How to Stay Grounded in a World of Cosmic Speculation

Not every question needs an answer right away. And not every headline deserves our belief. In a time when mystery travels faster than truth, staying grounded is a choice. Here are ways to keep your balance without closing your mind.

- Ask better questions

Don’t rush to label something as real or fake. Instead, ask: What’s the evidence? What do other experts say? What’s still unknown? - Check for peer-reviewed research

Trust claims that come with published studies, not just headlines. Look to sources like NASA, arXiv, or Nature Astronomy for reliable information. - Watch for vague language

Words like “may,” “could,” or “possibly” are not conclusions. They signal uncertainty. Use them as cues to dig deeper, not take things at face value. - Respect experts, but verify the data

Even brilliant scientists can be wrong. Look at their methods and whether their claims are supported by other researchers. - Follow facts, not feelings

Sensational stories spread fast, but real science often unfolds quietly. Be more interested in data than drama. - Let curiosity lead, but let evidence guide

Stay open. Wonder is powerful—but it should walk alongside discernment, not replace it. - Give time its due

Big discoveries are not confirmed overnight. Let time and peer review do their work before forming strong opinions. - Embrace uncertainty

The unknown is not a flaw. It is the space where learning begins. Stay humble about what we cannot yet explain.

In a world filled with noise, let your mind be a clear place. You do not need to have an answer for everything. You only need the courage to keep asking, and the patience to wait for what truth reveals in time.

What We Choose to See

3I ATLAS may be nothing more than a passing comet. Or it may be something we are not yet equipped to understand. But perhaps its real purpose is not to be solved, but to provoke something we have forgotten how to feel.

It made us pause. It made us wonder. It reminded us that not everything can be explained on demand. And in a world obsessed with certainty, that reminder is radical. Because the real message might not be in the object at all. It might be in how we choose to meet the unknown—whether with fear, denial, curiosity, or courage.

Science begins not with answers, but with attention. And sometimes, the most important discoveries do not come from proving what something is, but from changing how we see. So keep looking up. Not to escape this world, but to better understand your place in it. Let mystery make you thoughtful, not afraid. Let it sharpen your questions, not silence them. In the end, the sky does not just reveal what is out there. It reveals what still lives in us.

Featured Image by ESA/Hubble, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Loading...