Harvard’s Best-Kept Secret Is a Cuban-American Woman From Chicago Public Schools

Imagine a 14-year-old girl climbing into a cockpit. Not as a passenger. As a pilot. Behind her sits an aircraft she built with her own hands. No instructor beside her. Just her, the machine, and the open sky. Most teenagers at 14 are figuring out algebra. She was solo-flying a single-engine plane she constructed herself a full year before she could legally sit behind the wheel of a car.

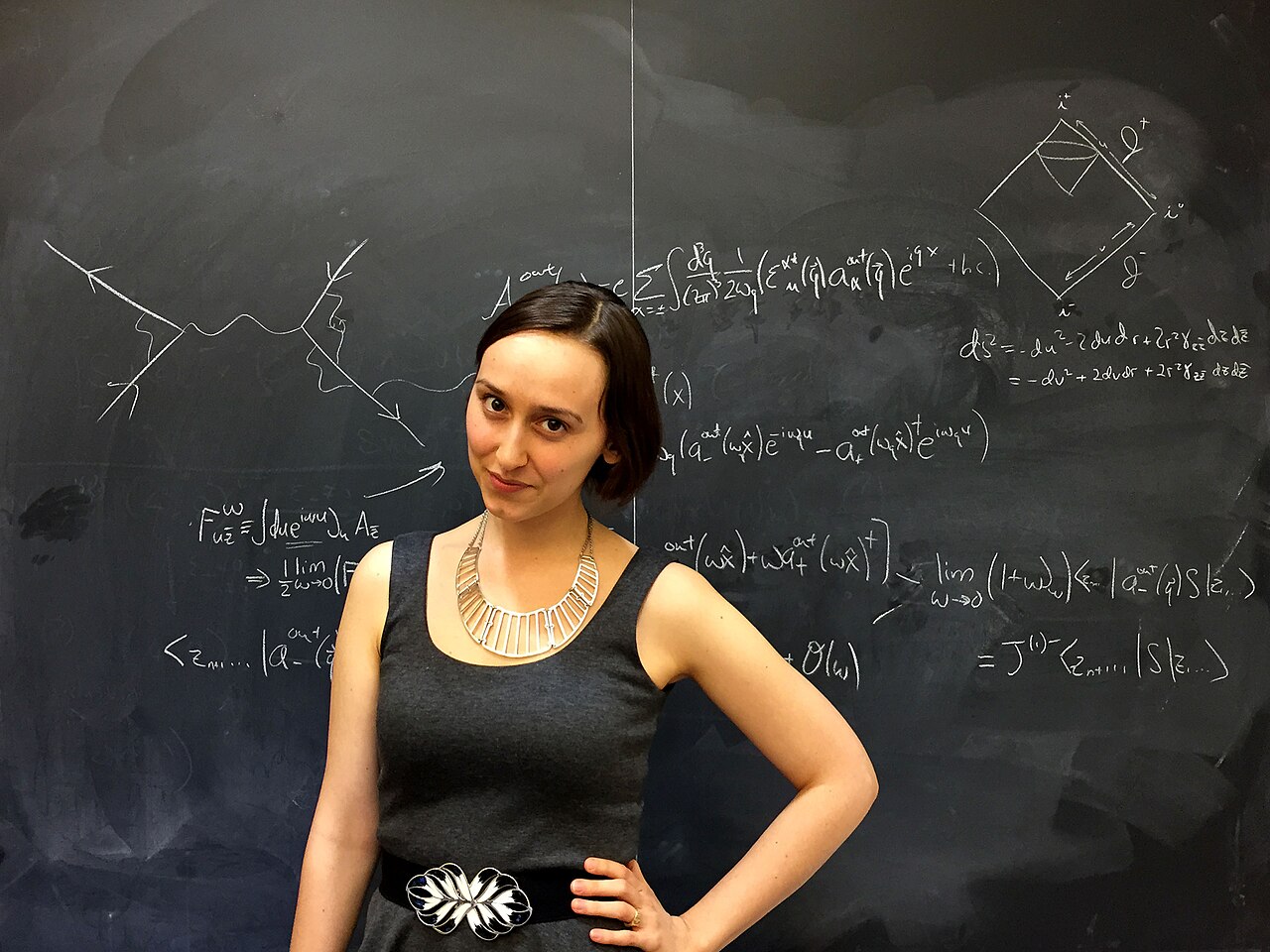

Who is she? A first-generation Cuban-American from the public schools of Chicago. A woman whose name is now spoken in the same breath as Albert Einstein’s. A physicist whose work could one day rewrite how humanity understands the universe. Her name is Sabrina Gonzalez Pasterski. And her story is only getting started.

She’s Not Just Smart, She Builds Planes

Pasterski’s love affair with flight did not begin in a classroom. It started at age 9, on her very first airplane ride. Something clicked that day, not just curiosity, but full obsession. By 10, she had built an engine. By 12, a complete airplane. By 14, she climbed into that plane and flew it solo.

“Building an airplane from a kit and flying as a child, I longed to understand the physics, application and reach of flight,” she said in a 2012 Scientific American interview. Most kids her age were riding bikes. Pasterski was chasing clouds.

Born and raised in Chicago, she came up through public schools, shaped by a Cuban-American family that had no blueprint for what she would become. No legacy admissions. No prep school pedigree. Just raw hunger and a mind that refused to stop asking why.

What set her apart from other gifted children was not just intelligence; it was application. She did not read about how things worked and file that knowledge away. She built them. She tested them. She got in them and flew. That hands-on drive would carry her from a Chicago runway all the way to the halls of MIT and Harvard, and eventually to one of the most important physics research centres in the world.

From Waitlisted to Valedictorian

Harvard believes the next Einstein is among us. Her name is Sabrina Gonzalez Pasterski, a prodigy who is studying the universe in silence. pic.twitter.com/IM3RHQr2Z5

— Math Files (@Math_files) January 27, 2026

MIT almost said no. Pasterski was waitlisted before she got in a detail that, in hindsight, feels almost absurd. Once inside, she did not blend into the crowd. She graduated first in her MIT Physics class, the first woman ever to achieve that distinction, with a perfect 5.0 GPA. From MIT, she went straight to Harvard as a PhD candidate in Physics at just 21 years old.

At 19, Scientific American named her to their “30 Under 30” list. Forbes followed with their own version when she was 21, and she made their All-Star list in 2015. Before most people her age had figured out a career path, Pasterski had already built a reputation that made physicists twice her age stop and pay attention.

What she carried into Harvard was not just talent. She carried a hunger to push limits, academic, intellectual, and personal. Harvard, one of the most demanding academic institutions on earth, was about to see exactly what that hunger could produce.

The Discovery That Made Hawking Take Notice

In 2014, deep into her PhD work at Harvard, Pasterski and her colleagues made a discovery that put her name in front of one of the greatest scientific minds of the modern era.

She and her team identified something called the “spin memory effect” a phenomenon with the potential to detect and verify the cumulative effects of gravitational waves. Gravitational waves, first predicted by Einstein and confirmed by experiment in 2016, are ripples in spacetime caused by violent cosmic events like colliding black holes. Finding a way to measure their effects more precisely carries enormous weight for theoretical physics.

Her advisor, Andrew Strominger, the Gwill E. York Professor of Physics and director of Harvard’s Center for the Fundamental Laws of Nature, gave Pasterski free rein during her second year to study any subject she chose with anyone she liked. That kind of academic freedom is rare. It does not get handed to PhD students without a very good reason.

In 2015, Pasterski published an individual paper on her findings. In 2016, Stephen Hawking cited that paper, along with two co-authored papers, in his own published work. When Stephen Hawking adds your name to his footnotes, the physics world listens.

Her dissertation was later published in Physics Reports, making her only the second Harvard PhD candidate in history to earn that distinction. She received her PhD in 2019.

What She’s Actually Working On (And Why It Matters)

After Harvard, Pasterski completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the Princeton Centre for Theoretical Science. What she works on is not easy to summarise without a physics degree, but its importance is hard to overstate.

Her research covers quantum gravity, holography, black holes, and spacetime. She works on questions like how to explain gravity through the lens of quantum mechanics, and how to make sense of infinite-dimensional symmetry enhancements of the S-matrix. Her current research focuses on scattering in asymptotically flat spacetimes and constructing a putative codimension 2 dual CFT. These are problems at the outer edge of human knowledge, places where our current models of the universe run out of answers.

Harvard’s website describes her as someone who believes high-energy theoretical physics “holds the potential to transform multidisciplinary fields.” She has said she sees no limit to what physics can achieve and treats the word “impossible” as a challenge.

“I don’t know exactly what problem I will or will not end up solving, or what exactly I’ll end up working on in a couple of years,” she told Discovery Canada. “The fun thing about physics is that you don’t know exactly what you’re going to do. And normally things just change very quickly — kind of irreversibly — if they’re really right.” That comfort with the unknown, that openness to wherever the work leads, may be one of her greatest scientific gifts.

She Turned Down $1.1 Million: Here’s Why

After Princeton, Pasterski faced a choice that most academics would consider a dream. Brown University offered her $1.1 million to join as an assistant professor. It was a serious offer from a serious institution. She said no.

Instead, she joined the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in 2021. For anyone who knew her work, the decision made complete sense. Perimeter stands as one of the world’s leading centres for theoretical physics research. Money, for Pasterski, was never the point.

At Perimeter, she founded and leads the Celestial Holography Initiative. Her team works on encoding the universe as a hologram, an effort to unite our understanding of spacetime with quantum theory. These two pillars of modern physics have long refused to fully reconcile with each other. Pasterski and her team are building the bridge.

Whether that bridge gets completed in her lifetime or not, the work she does now may one day be the scaffolding on which future generations of physicists stand.

A Voice for Girls in STEM

Pasterski’s reach does not stop at research papers. She is, in her own right, a public figure, and she uses that position with intention.

In 2016, she received an invitation to the White House as an advocate for Let Girls Learn, the initiative launched by President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama to help girls around the world access quality education. Her presence there made a statement as a first-generation Cuban-American woman from Chicago public schools, standing in the White House because of what she had built with her mind.

She also runs a YouTube channel called PhysicsGirl, where she breaks down her research in a way that does not require a PhD to follow. At a time when science often gets locked behind paywalls and academic language, she brings it outside. She makes it feel alive and within reach.

Her story matters to every Hispanic girl who has ever been told, by silence or by words, that physics is not for her. Pasterski has never accepted that idea. She has lived the opposite, every single day.

What “The Next Einstein” Really Means

Calling someone “the next Einstein” is a serious claim. It carries the kind of weight that can reduce a complex human being to a headline. Yet in Pasterski’s case, people keep saying it because her work earns it.

What made Einstein matter was not just his intelligence. It was his refusal to accept the world as fixed. He asked questions that seemed absurd until they weren’t. He sat with uncertainty long enough for answers to come.

Pasterski seems cut from that cloth. She builds things. She tests them. She publishes papers that Hawking cites. She turns down $1.1 million because she would rather do work that actually matters. She speaks about physics the way other people speak about love.

“It’s not like a 9-to-5 thing,” she told Yahoo. “When you’re tired you sleep, and when you’re not, you do physics.” That is not the description of a career. That is the description of a calling.

Whatever Pasterski discovers next, one thing holds. She is far from done. And if she is right, if high-energy theoretical physics can produce breakthroughs we have not yet imagined, then what she builds in the years ahead may change not just science, but the way we see everything around us. A girl from Chicago built a plane and flew it into the sky. Where she goes from here, only physics knows.

Featured Image Source: Wikimedia Commons https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Sabrina_Gonzalez_Pasterski_2014_2.jpg/1280px-Sabrina_Gonzalez_Pasterski_2014_2.jpg

Loading...