Look: A Bored Security Guard On His First Day Drew Eyes On An 88-Year-Old Painting Worth $1 Million.

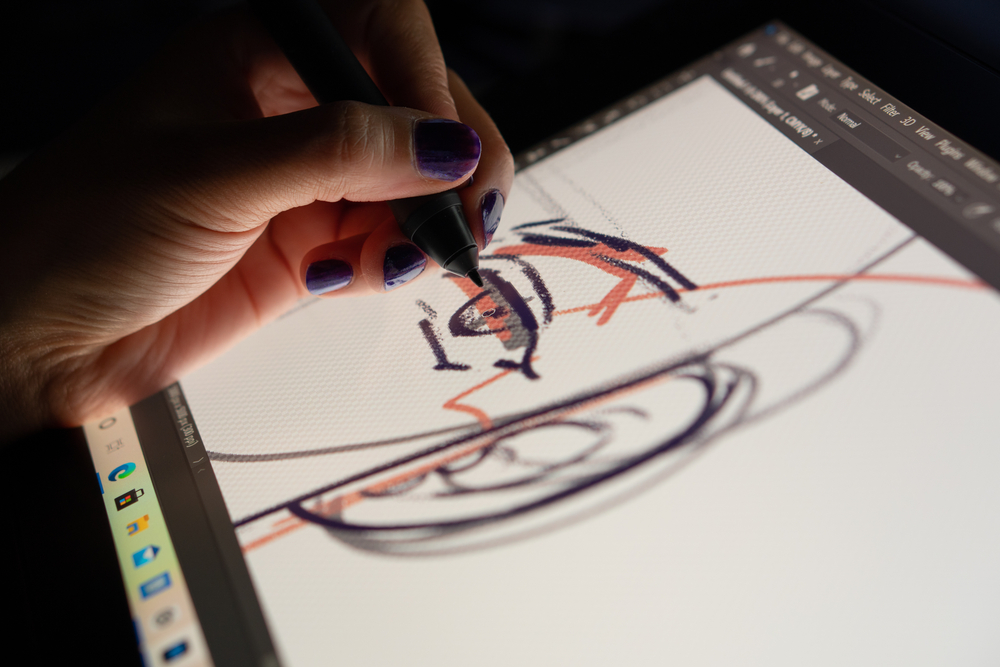

In December, an event at the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center in Yekaterinburg, Russia, stunned both the art world and the public. A security guard, newly hired and working his very first day, took a ballpoint pen to Anna Leporskaya’s 1930s avant-garde painting Three Figures and drew eyes onto the faceless forms. The act was at once absurd and devastating. The work, valued at over one million dollars and on loan from the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, had stood for nearly a century as a carefully preserved example of Soviet-era abstraction. Yet in a few seconds, what had survived history, politics, and time itself was altered by human negligence. Although conservators estimate that the painting can be restored for about 250,000 roubles, the damage was more than financial. It forced curators, officials, and the public to confront a sobering truth: cultural treasures exist on a fragile edge between preservation and loss, and the choices of one person can alter them forever.

This story is more than a headline about vandalism. It is a lens on human behavior, on how institutions assign responsibility, and on what societies value enough to protect. A single act of recklessness, whether born of boredom, instability, or ignorance, left a mark not only on Leporskaya’s canvas but on the conversation around accountability. When we look at the eyes now scribbled across those abstract faces, we see more than vandalism. We see a reflection of our own tendency to overlook value until it is threatened, and of how easily carelessness can undo decades of careful preservation.

What We Value

The obvious question is: why does this painting matter so much? To the untrained eye, Three Figures might appear simple—muted shapes, faceless forms, a composition stripped of ornament. Yet its meaning is rooted in a turbulent chapter of art history. Leporskaya studied under Kazimir Malevich, the founder of Suprematism, whose radical vision sought to break art free from the constraints of realism and political propaganda. In the Soviet Union of the 1930s, such abstraction was not just stylistic experimentation; it was a subtle act of defiance against a system that demanded artists glorify the state through socialist realism. The facelessness of the figures, the deliberate absence of eyes or expressions, was part of Leporskaya’s intent. It pointed to universality rather than individuality, to a collective humanity beyond the dictates of ideology.

When the guard drew eyes onto the figures, he wasn’t just altering paint on canvas. He was undoing an artistic decision that carried historical and philosophical weight. The value of Three Figures is not merely in its estimated price of over one million dollars but in its role as a witness to the struggles of creativity under authoritarian pressure. It is a record of an artist who carved her space in a movement dominated by giants like Malevich, an artist whose voice, though less famous, still carried the urgency of her time. To change her work, even in such a seemingly trivial way, is to distort her message.

This incident forces us to think about how we measure value. We live in a world where numbers dominate—bank balances, property values, prices on auction house catalogues. Yet as this case shows, true worth lies in meaning, not just in money. What Leporskaya gave to the world was not a financial asset but a fragment of human thought preserved in pigment and canvas. Similarly, in our personal lives, the things that matter most—our health, our relationships, our creativity—rarely have a price tag. And yet, like the painting, they are irreplaceable. The guard’s careless doodle is a reminder that when we fail to recognize value before it is damaged, we may discover too late that what was lost cannot be fully restored.

The Human Element

The question of motive lingers like a shadow over this case. Why did the guard do it? Reports describe him as “bored,” and the curator suggested it was a “lapse in sanity.” It is possible that psychological stress or sheer thoughtlessness played a role. What matters is that the incident reveals the frailty of human judgment. A man hired to protect became the one who inflicted harm. He was dismissed from his job immediately, and prosecutors, after pressure from the Ministry of Culture, opened a criminal case. He now faces fines and the possibility of prison. Yet the story is not simply about his individual guilt. It is about how institutions and societies delegate responsibility, sometimes without adequate preparation.

The Yeltsin Center confirmed that the guard was employed by a private security contractor, not directly by the museum. Outsourcing security may save costs, but it also raises risks. Guards are often placed in positions of high responsibility without specialized training in art handling or cultural awareness. They may not grasp the significance of the objects under their watch. In this case, the result was catastrophic: a guard entrusted with safeguarding an international loan lacked either the understanding or the stability to fulfill his duty. The failure was not his alone but part of a broader system that prioritized efficiency over expertise.

The implications extend beyond art galleries. In workplaces, communities, and governments, responsibility is often assigned without equipping people to handle it. A single weak link in a chain of accountability can cause damage that ripples outward. The vandalism at the Yeltsin Center is a dramatic example, but it mirrors countless smaller failures we see in daily life. A neglected safety procedure that leads to an accident. A careless word that destroys trust in a relationship. A thoughtless decision that derails months of progress. Human error is inevitable, but without support systems, oversight, and preparation, its consequences can be devastating.

The World's Sarah Birnbaum reports on a security guard at a Russian art gallery who was fired after drawing eyes onto faceless images of an avant-garde painting called "Three Figures," by Anna Leporskaya. He was allegedly bored. Check out the image and see for yourself. pic.twitter.com/2nWS1YHFKN

— The World (@TheWorld) February 11, 2022

Protecting What Matters

After the vandalism, the Yeltsin Center quickly installed protective screens over the rest of the exhibition. This measure may prevent further incidents, but it highlights a familiar pattern: we often act only after harm has already been done. In the personal sphere, this is equally true. People ignore health until illness forces a reckoning. They neglect relationships until distance or conflict makes repair difficult. They undervalue their mental well-being until breakdown compels them to pay attention. Like museums, we wait until damage occurs to add safeguards, rather than protecting value proactively.

The challenge is that prevention often feels invisible. When nothing goes wrong, it is easy to dismiss protection as unnecessary. Yet history shows us that the cost of repair is always higher than the cost of care. Restoring Three Figures will require months of expert labor and thousands of dollars. Restoring trust after betrayal can take years. Rebuilding health after years of neglect may demand treatments and sacrifices far greater than the daily habits that could have preserved it. Prevention is rarely dramatic, but it is always wiser than reaction.

Museums now face a dilemma familiar to anyone who guards something precious. Should they place every masterpiece behind glass, keeping visitors at a distance but ensuring safety? Or should they trust the public, knowing that intimacy and vulnerability sometimes invite harm? This balance between accessibility and protection mirrors the choices we make in life. How much do we shield ourselves from risk, and how much do we stay open to connection? Too much distance can rob us of authentic experience. Too little protection can expose us to irreversible loss. The lesson of the Yeltsin Center is not that one path is correct, but that we must remain vigilant in striking the balance—both for art and for life.

all the new fans like: (Three Figures, by Anna Leporskaya, 1932–34) pic.twitter.com/reHVuusFHS

— ArtButMakeItSports (@ArtButSports) February 22, 2024

The Call to Action

The story of Leporskaya’s Three Figures now includes not only the brushstrokes of the 1930s but also the pen marks of 2021. Even after restoration, the incident will remain part of its history. In this way, it embodies a truth that applies to all fragile treasures: damage can be repaired, but it can never be erased. This truth compels us to take responsibility not only for paintings on gallery walls but for the intangible masterpieces we live with every day—our health, our relationships, our environment, our shared culture.

The call to action is simple yet profound. We must recognize value before it is damaged, not after. That means treating cultural heritage as more than decoration, investing in its protection and education. It means treating people with care before conflict arises, not apologizing only when the damage is done. It means building habits of respect, accountability, and mindfulness, so that prevention becomes second nature. In the guard’s careless doodle we see how quickly neglect can scar something irreplaceable. But we also see an invitation: to choose differently, to act with awareness rather than impulse.

The eyes scrawled across Leporskaya’s figures were never part of her vision, yet they have forced us to look more closely—at art, at society, at ourselves. They challenge us to ask whether we are truly guarding what matters most. Because whether it is a century-old painting or a fragile human bond, the time to protect it is always now.

Loading...