A Breakthrough Antibiotic Discovery Could Change the Fight Against Superbugs

For most of modern history, antibiotics have been treated as a solved problem. A patient gets sick, a doctor prescribes a pill, and within days the infection fades. That simple narrative shaped medicine, population growth, and even human psychology, creating a sense that bacterial disease was something we had permanently outgrown.

Yet beneath that confidence, bacteria have been quietly evolving. Today, drug resistant infections kill millions of people each year, and the number continues to rise. The microbes have not changed their ancient role as masters of adaptation. What has changed is our relationship to discovery. For decades, scientists believed that the golden age of antibiotics was behind us and that nearly all useful compounds had already been found.

Recent breakthroughs are now challenging that assumption in dramatic ways. Researchers are discovering powerful new antibiotics not in exotic rainforests or deep sea vents, but hidden within familiar molecules, well studied bacteria, and even vast digital libraries scanned by artificial intelligence. These discoveries suggest that humanity may not be running out of antibiotics at all. Instead, we may be relearning how to listen to nature and technology with fresh eyes.

This article explores how scientists uncovered a new antibiotic molecule that is up to 100 times stronger than existing treatments, why it remained invisible for decades, and how this discovery connects to a broader scientific awakening in the fight against the world’s deadliest superbugs.

The Growing Crisis of Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance, often shortened to AMR, occurs when bacteria evolve the ability to survive drugs designed to kill them. This is not a flaw in biology. It is biology working exactly as intended. Bacteria replicate rapidly, mutate constantly, and share survival traits with neighboring microbes. When antibiotics are overused or misused, the most resilient bacteria survive and pass on their defenses.

According to the World Health Organization, AMR is one of the top threats to global health. Pathogens such as methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin resistant Enterococcus, and multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii are now common in hospitals worldwide. These organisms can survive on surfaces for long periods, evade multiple classes of drugs, and infect patients whose immune systems are already compromised.

One of the most troubling aspects of this crisis is economic rather than biological. Developing new antibiotics is expensive, slow, and often unprofitable. Unlike chronic disease drugs that patients take for years, antibiotics are used briefly and sparingly. As resistance grows, pharmaceutical investment shrinks. The result is a widening gap between the pace of bacterial evolution and the pace of human innovation.

For many years, the prevailing belief was that the antibiotic pipeline had run dry. Scientists assumed that nature’s easily discoverable antimicrobial compounds had already been cataloged. What recent research reveals is that this belief may have been rooted in a narrow way of looking.

The Hidden Antibiotic That Was There All Along

One of the most striking discoveries in recent years emerged from research conducted at the University of Warwick and Monash University. Chemists working within a collaborative initiative revisited a well known antibiotic called methylenomycin A. This compound was discovered roughly 50 years ago and has been synthesized many times since.

What had never been done was deceptively simple. No one had tested the intermediate molecules produced during methylenomycin A’s biosynthetic process for antibiotic activity.

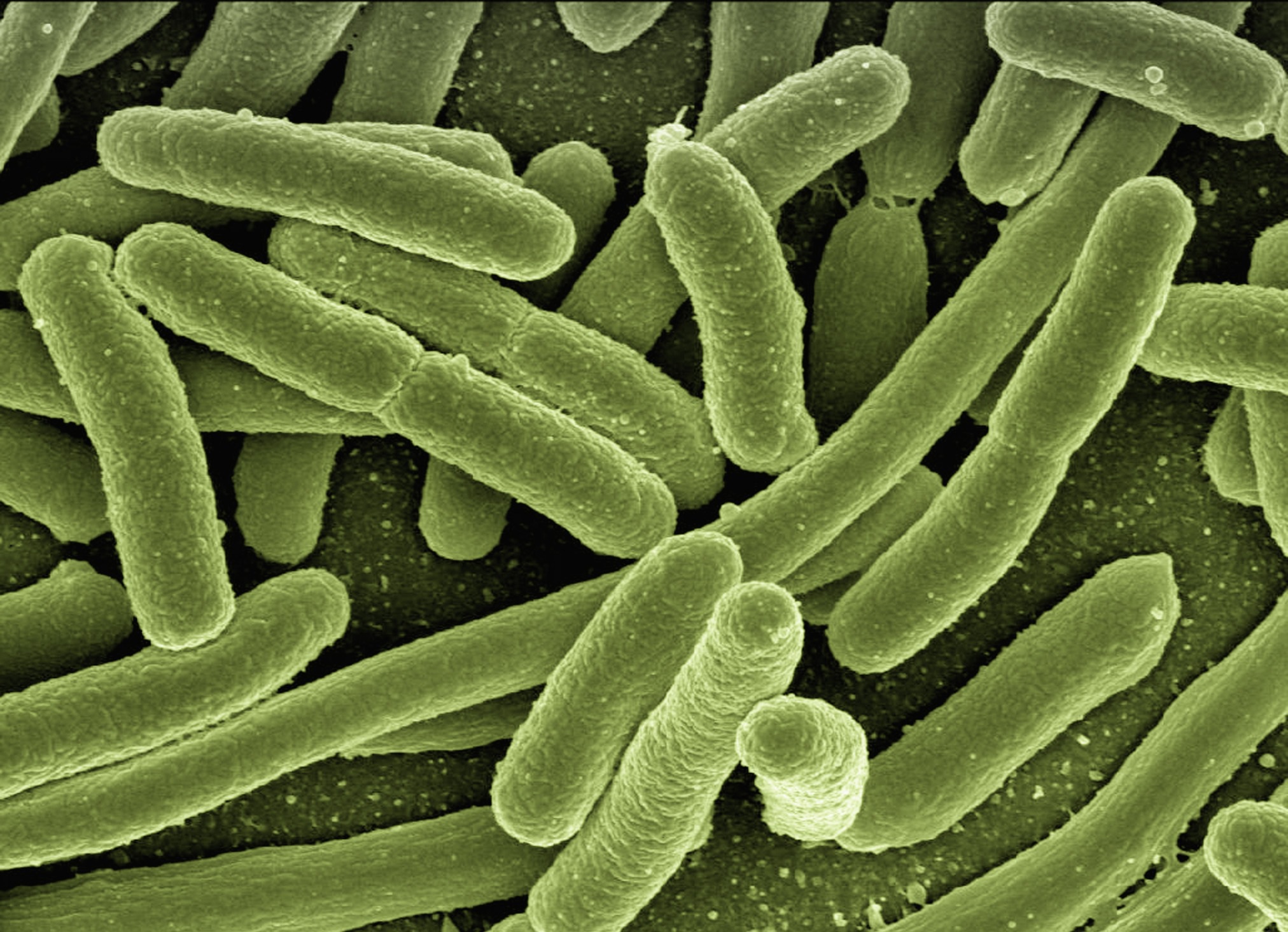

Inside the bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor, methylenomycin A is created through a sequence of chemical steps. Each step produces a temporary intermediate molecule that exists only briefly before being transformed into the final product. These intermediates were assumed to be biologically irrelevant.

By selectively disabling certain biosynthetic genes, researchers forced the bacterium to stop mid process. This allowed them to isolate and study intermediate compounds that had been effectively invisible for decades.

One of these molecules, known as pre methylenomycin C lactone, stunned researchers. When tested against Gram positive bacteria, it demonstrated antibacterial activity more than 100 times stronger than methylenomycin A itself. It proved especially potent against MRSA and VRE, two of the most dangerous and treatment resistant pathogens in modern medicine.

Even more remarkable, laboratory tests showed no detectable resistance emerging under conditions that typically generate resistance to last resort antibiotics like vancomycin.

This molecule had been hiding in plain sight inside one of the most extensively studied antibiotic producing bacteria on Earth.

Why Nature May Favor Weaker Antibiotics

An obvious question arises. If pre methylenomycin C lactone is so powerful, why does Streptomyces coelicolor primarily produce a weaker antibiotic instead?

The answer may lie in ecology rather than medicine. In nature, killing every neighboring microbe is not always advantageous. A bacterium that wipes out its surroundings may destabilize its own environment. Producing a weaker compound can regulate competition without triggering an evolutionary arms race.

From this perspective, methylenomycin A may represent an evolutionary compromise. The stronger intermediate existed first, but natural selection favored a gentler chemical strategy that balanced defense with coexistence.

This insight carries profound implications for drug discovery. It suggests that many organisms may possess dormant or suppressed chemical weapons that are never deployed at full strength in nature but can be repurposed for human medicine.

Instead of searching for entirely new antibiotics, scientists are beginning to mine the hidden layers within known biosynthetic pathways.

A New Paradigm for Antibiotic Discovery

The discovery of pre methylenomycin C lactone points to a fundamental shift in how antibiotics can be found. Rather than screening millions of random compounds, researchers can investigate the chemical assembly lines already present in nature.

Every natural antibiotic is built step by step. Each step is an opportunity for biological activity. By interrupting these pathways and studying their intermediates, scientists may uncover a vast and largely unexplored reservoir of antimicrobial molecules.

This approach is especially promising because natural products have already been shaped by millions of years of evolutionary pressure. They often interact with biological systems more effectively than purely synthetic drugs.

Importantly, the Warwick and Monash teams also developed a scalable synthetic route for pre methylenomycin C lactone. This allows chemists to create analogs, modify its structure, and study how it kills bacteria. Scalability is essential if a molecule is ever to move from the lab to the clinic.

Another Breakthrough: Targeting Bacterial Weak Points

While hidden intermediates represent one frontier, another breakthrough comes from designing antibiotics that target bacterial structures that do not easily mutate.

At the University of Liverpool, researchers developed a new antibiotic platform known as Novltex. Inspired by earlier work on teixobactin, Novltex targets lipid II, a molecule essential for building bacterial cell walls.

Lipid II is sometimes described as a bacterial Achilles’ heel. It is critical for survival and does not readily change without killing the organism. By targeting this structure, Novltex avoids one of the main drivers of resistance.

Laboratory tests showed that Novltex kills MRSA and Enterococcus faecium rapidly and at very low doses. It outperformed several existing antibiotics and showed no toxicity in human cell models. Its modular design allows scientists to generate entire libraries of related compounds, fine tuning safety and effectiveness.

The significance of this approach is durability. Instead of chasing bacteria as they mutate, scientists are anchoring treatments to biological constants.

Artificial Intelligence Enters the Antibiotic Hunt

Perhaps the most futuristic development in antibiotic discovery comes from the application of artificial intelligence. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and McMaster University trained machine learning models to identify compounds capable of killing drug resistant bacteria.

By feeding the algorithm data on thousands of chemical structures and their effects on bacterial growth, the system learned to recognize subtle patterns that human researchers might overlook. When applied to a library of nearly 7,000 compounds, the model identified several promising antibiotics in under two hours.

One standout compound, later named abaucin, proved highly effective against Acinetobacter baumannii, a pathogen notorious for hospital outbreaks and battlefield infections. Unlike broad spectrum antibiotics, abaucin targets this bacterium specifically. This narrow focus reduces the risk of disrupting beneficial gut microbes and slows the spread of resistance.

In animal models, abaucin successfully treated infections without harming other bacterial species. Further studies revealed that it interferes with lipoprotein trafficking, a process that Acinetobacter performs in a slightly different way than other bacteria.

AI did not replace human scientists in this process. Instead, it acted as a powerful extension of perception, scanning chemical space far faster than traditional methods allow.

What These Discoveries Have in Common

At first glance, hidden biosynthetic intermediates, modular synthetic antibiotics, and AI driven drug discovery may seem unrelated. In reality, they share a unifying theme.

All three approaches move beyond surface level observation.

Instead of asking what antibiotics are obvious, researchers are asking what has been overlooked. Instead of assuming resistance is inevitable, they are identifying immutable targets. Instead of relying solely on human intuition, they are partnering with intelligent systems that can detect patterns at immense scale.

This reflects a deeper shift in scientific thinking. Progress no longer comes only from finding new things, but from seeing familiar things differently.

A Systems View of Bacteria and Medicine

Bacteria are often framed as enemies to be eradicated. While this framing is understandable in clinical settings, it obscures a larger truth. Microbes are foundational to life on Earth. They shape ecosystems, cycles of nutrients, and even human biology.

From a systems perspective, antibiotic resistance is not merely a failure of medicine. It is feedback. It reflects how human activity interacts with microbial evolution. Overprescription, agricultural use of antibiotics, and environmental contamination all contribute to selective pressure.

The emerging generation of antibiotics suggests a more nuanced relationship. By learning how bacteria regulate their own chemical arsenals, and by targeting conserved biological processes, medicine begins to work with the logic of life rather than against it.

Parallels With Ancient Knowledge

Interestingly, the idea that powerful tools are hidden within familiar systems is not new. Many ancient traditions emphasized the importance of subtlety, balance, and latent potential. Knowledge was often described as something revealed through attention rather than conquest.

Modern science is arriving at a similar insight through empirical methods. The most potent antibiotics were not discovered by traveling farther, but by looking deeper. The most resilient strategies are not those that dominate, but those that align with fundamental structures.

This does not diminish the rigor of science. It expands its philosophical horizon.

The Road Ahead

Despite the excitement, none of these antibiotics are ready for widespread clinical use. Pre clinical testing, animal studies, safety trials, and regulatory approval all lie ahead. Many promising compounds fail along this path.

Still, the momentum is undeniable. With scalable synthesis, modular design, and AI assisted discovery, the antibiotic pipeline is no longer stagnant. It is evolving.

Future research will likely combine these approaches. AI may help identify promising biosynthetic intermediates. Synthetic platforms may refine natural compounds. Ecological insights may guide responsible use.

Rethinking the Narrative of Scarcity

For years, the dominant story around antibiotics was one of scarcity and decline. We were running out of options, falling behind unstoppable superbugs, and facing an inevitable post antibiotic era.

The discoveries described here do not eliminate the threat of antimicrobial resistance. But they challenge the fatalism surrounding it.

They suggest that solutions emerge when perception shifts. When assumptions are questioned. When scientists are willing to revisit the familiar with curiosity rather than dismissal.

Discovery as Remembrance

In a sense, the new antibiotics were never truly gone. They were embedded within biological systems, chemical pathways, and data patterns, waiting to be recognized.

The discovery of pre methylenomycin C lactone reminds us that even well studied organisms can still surprise us. Novltex demonstrates that targeting biological constants can outmaneuver resistance. AI driven antibiotics show that intelligence, whether biological or artificial, thrives on pattern recognition.

Together, these breakthroughs point toward a future where medicine is not locked in an endless arms race, but engaged in a deeper dialogue with life itself.

If there is a lesson here beyond microbiology, it is this. Progress does not always require something new. Sometimes it requires remembering how to look.

Loading...