How Scientists Made Pancreatic Cancer Disappear in Experimental Models

For generations, pancreatic cancer has been regarded as one of medicine’s most unforgiving diagnoses. Often discovered late, resistant to treatment, and aggressive in its progression, it has quietly earned a reputation as a near-certain death sentence. Families, doctors, and researchers alike have long struggled with the limitations of existing therapies, watching promising drugs lose effectiveness as tumors adapt and return stronger than before.

So when headlines began circulating about scientists achieving the permanent disappearance of pancreatic cancer in experimental models, the news landed with unusual force. Not because cancer has never been cured in mice before, but because of how it was done. This time, the tumors did not simply shrink or pause. They vanished completely and did not return, even long after treatment stopped. Just as striking, the animals experienced minimal side effects, a rare outcome in aggressive cancer research.

The study, led by Mariano Barbacid at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre, represents a shift in how scientists think about treating not only pancreatic cancer, but cancer itself. Instead of searching for a single silver bullet, the researchers approached cancer as a complex, adaptive system that must be disarmed at multiple levels at once.

At first glance, this may appear to be another incremental scientific advance. But when viewed through a wider lens, this breakthrough points toward a deeper transformation unfolding in modern medicine. One that mirrors ideas long found in systems biology, ancient healing philosophies, and even spiritual understandings of balance and resilience in living systems.

Why Pancreatic Cancer Has Remained So Deadly

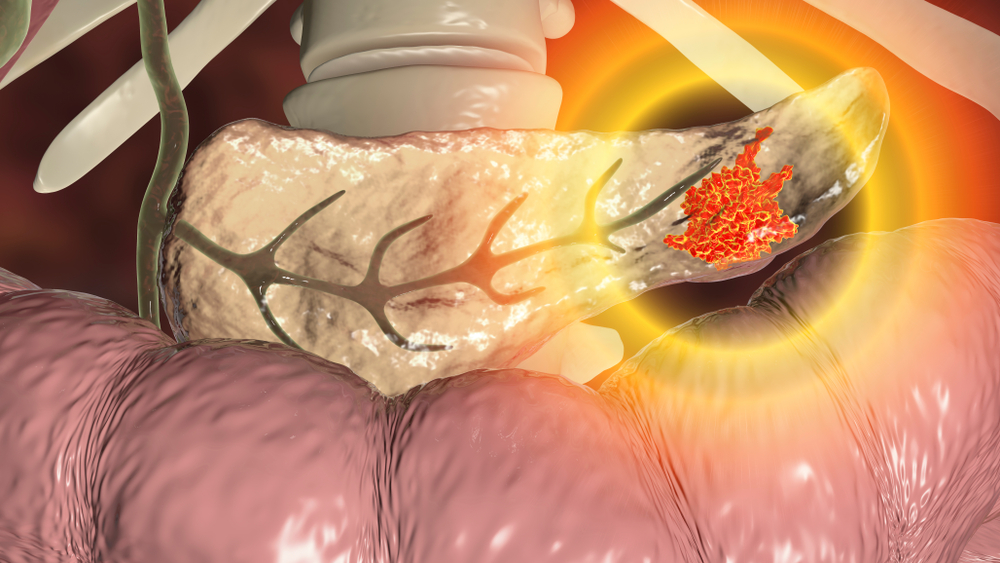

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the most common form of pancreatic cancer, is notorious for its poor prognosis. Fewer than one in ten patients survive five years after diagnosis. In many cases, the disease has already reached an advanced stage by the time symptoms appear, which often resemble common digestive issues like bloating, fatigue, or back pain.

Beyond late detection, pancreatic cancer possesses a biological resilience that makes it exceptionally hard to treat. The tumors grow within a dense, fibrotic environment that shields them from chemotherapy and immune attack. Even when drugs successfully target cancer cells, the tumors frequently evolve resistance within months.

At the heart of this resilience lies a genetic mutation that appears in roughly 90 percent of pancreatic cancers. This mutation affects a gene called KRAS.

KRAS functions like a master switch that controls cell growth and division. In healthy cells, it turns on and off as needed. In cancer cells, KRAS becomes stuck in the on position, relentlessly telling cells to grow, divide, and survive. For decades, KRAS was labeled “undruggable” because of its smooth molecular surface and lack of obvious binding sites.

In recent years, scientists finally developed drugs capable of inhibiting KRAS signaling. These drugs marked a major milestone in cancer research and initially raised hopes for pancreatic cancer treatment. Unfortunately, those hopes were tempered by a familiar pattern. Tumors quickly adapted, activating alternative pathways to bypass the blocked signal and resume growth.

Cancer, it turns out, is not a static enemy. It is an adaptive, learning system.

The Problem With Single Target Therapies

Traditional drug development has often followed a reductionist mindset. Identify the main driver of disease, block it, and expect the system to collapse. This approach works well for some conditions, but cancer repeatedly exposes its limitations.

When a single pathway is blocked, cancer cells respond by rerouting signals through backup systems. This biological flexibility is not accidental. It is the result of millions of years of evolution favoring survival under stress.

In pancreatic cancer, blocking KRAS alone creates pressure on the tumor. In response, cancer cells activate other growth pathways such as EGFR, HER2, or STAT3. These pathways act like detours, allowing the tumor to keep functioning even when its main road is closed.

The result is a temporary response followed by relapse.

This is where the Spanish research team chose to think differently.

A Triple Therapy Strategy That Corners the Cancer

Rather than targeting KRAS at a single point, the researchers designed a combination therapy that attacks the cancer from three distinct angles simultaneously.

The first drug targets KRAS directly, blocking the primary signal that drives tumor growth. The second drug inhibits EGFR and HER2, pathways that cancer cells often use as escape routes when KRAS is suppressed. The third drug disables STAT3, a survival mechanism that helps cancer cells withstand stress and resist treatment.

In essence, the therapy shuts down the cancer’s engine, its detours, and its emergency backup system all at once.

When tested in multiple mouse models, including genetically engineered mice and tumors derived from human patients, the results were remarkable. Tumors regressed completely. More importantly, they did not return even months after treatment ended.

Equally significant was what did not happen. The mice did not experience severe toxicity or major side effects, suggesting that the therapy selectively targeted cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue.

The findings were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, one of the most respected scientific journals in the world.

A Triple Therapy Strategy That Corners the Cancer

Skepticism is natural whenever cancer cures in mice make headlines. Many promising treatments have failed to translate into human success. The researchers themselves emphasized caution, noting that human clinical trials are not yet underway and that optimizing the therapy for patients will be complex.

However, several factors distinguish this study from earlier attempts.

First, the durability of the response is unusual. Tumors did not merely shrink temporarily. They disappeared and remained absent long after treatment stopped. This suggests that the cancer was not simply suppressed, but functionally dismantled.

Second, the therapy was effective across different experimental models, including human tumor samples grown in laboratory settings. This increases confidence that the approach targets fundamental mechanisms rather than model specific quirks.

Third, the treatment addressed the core issue that has plagued pancreatic cancer therapies for decades, resistance. Instead of reacting to resistance after it emerges, the therapy anticipates it and blocks multiple escape routes from the start.

This shift from reactive to proactive design marks a significant evolution in cancer strategy.

Cancer as a System, Not a Target

At a deeper level, this research reflects a broader transformation in how science understands disease. Cancer is no longer viewed as a single malfunctioning component, but as a complex system interacting with its environment.

Systems biology, an interdisciplinary field that studies how networks of genes, proteins, and cells interact, has increasingly shown that biological outcomes emerge from relationships rather than isolated parts. When one element changes, the system reorganizes.

The triple therapy approach aligns perfectly with this perspective. Instead of fighting cancer on one front, it alters the system in such a way that cancer can no longer adapt.

Interestingly, this way of thinking mirrors principles found in ancient healing traditions. Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, and other holistic systems have long emphasized balance, interconnectedness, and the importance of addressing root causes rather than symptoms.

While modern science operates with molecules and pathways rather than energy flows and meridians, the underlying insight is strikingly similar. Complex problems require multi layered solutions.

Implications Beyond Pancreatic Cancer

Although this study focuses on pancreatic cancer, its implications extend far beyond a single disease.

KRAS mutations are present in several other aggressive cancers, including lung and colorectal cancers. The success of a multi target strategy suggests that similar combination therapies could be designed for other difficult to treat tumors.

More broadly, the research challenges the pharmaceutical industry’s long standing preference for single agent therapies. Combination treatments are more complex to develop, regulate, and administer. But they may be far more effective against adaptive diseases.

This shift may also influence how clinical trials are designed, moving away from linear testing of isolated drugs toward integrated strategies that reflect biological reality.

The Human Timeline and Ethical Patience

Despite the excitement, it is crucial to maintain realistic expectations. Translating experimental therapies from mice to humans takes time. Safety, dosage, interactions, and long term effects must be carefully studied.

Dr. Barbacid and his team have been explicit that human trials are not imminent. This honesty matters. False hope can be as harmful as no hope at all.

Yet patience does not negate progress. Each step forward reshapes the landscape of possibility. What once seemed impossible gradually becomes plausible, then practical.

For patients and families affected by pancreatic cancer, this research represents something precious. Not a promise of immediate cure, but evidence that the wall is cracking.

A Deeper Reflection on Adaptation and Resilience

Beyond its clinical implications, this breakthrough invites a broader reflection on how life responds to pressure.

Cancer cells survive by adapting. They exploit redundancy, flexibility, and cooperation within biological networks. These same qualities allow healthy organisms to survive environmental challenges.

The difference lies in direction. Healthy systems adapt in ways that support the whole. Cancer adapts in ways that serve only itself.

The triple therapy works not by overpowering cancer with brute force, but by removing its capacity to adapt. It changes the context so that malignant strategies no longer function.

This principle echoes far beyond medicine. In ecology, psychology, and even social systems, lasting change often arises not from forceful suppression, but from altering the conditions that sustain harmful patterns.

Science, Humility, and the Future of Healing

One of the most refreshing aspects of this research is its humility. The scientists involved are careful not to overstate their findings. They acknowledge uncertainty, complexity, and the long road ahead.

This humility is a strength, not a weakness. It reflects a mature scientific culture that recognizes how much remains unknown.

At the same time, the study demonstrates boldness. It dares to confront one of medicine’s most stubborn challenges with a strategy that embraces complexity rather than avoiding it.

As science continues to evolve, breakthroughs like this remind us that progress is not always about discovering something entirely new. Sometimes it is about seeing familiar problems from a new perspective.

A Signal of Transformation

The permanent disappearance of pancreatic tumors in experimental models does not mean the battle is over. But it does suggest that the rules of the game are changing.

By treating cancer as a system rather than a single target, researchers are beginning to outmaneuver a disease that has long thrived on adaptability. This approach aligns cutting edge molecular science with timeless insights about interconnectedness and balance.

Whether or not this specific therapy reaches patients, it has already accomplished something important. It has expanded the imagination of what is possible.

In a field often defined by incremental gains and sobering statistics, that expansion alone is a quiet revolution.

Loading...