Scientists Believe They Have Uncovered the Cause of Bipolar Disorder

For decades, bipolar disorder has been one of the most misunderstood and hotly debated conditions in mental health. People who live with it often describe feeling as if their minds are constantly being pulled between extremes, from crushing lows that make everyday life feel unbearable to intense highs that can feel exhilarating at first but spiral into chaos just as quickly. Despite years of research, countless studies, and evolving treatments, one fundamental question has continued to loom over scientists, doctors, and patients alike.

What actually causes bipolar disorder?

Now, a massive new wave of genetic research is beginning to offer an answer that could reshape how the condition is understood, diagnosed, and treated. Instead of viewing bipolar disorder as an equal balance between depression and mania, scientists are uncovering evidence that one side of the illness may be doing far more of the biological work than the other. The implications of that discovery could help explain decades of misdiagnosis, overlapping symptoms with other mental illnesses, and why effective treatment has often felt frustratingly out of reach.

A Disorder Long Defined by Extremes

Bipolar disorder, formerly known as manic depression, is characterized by dramatic shifts in mood, energy, and behavior. These shifts range from depressive episodes marked by sadness, hopelessness, fatigue, and loss of interest, to manic or hypomanic episodes defined by heightened energy, reduced need for sleep, racing thoughts, impulsivity, and elevated or irritable mood.

Episodes can last days, weeks, or even months, and the pattern varies widely from person to person. Some people experience long stretches of emotional stability between episodes, while others cycle frequently or even experience symptoms of depression and mania at the same time.

Because the disorder presents so differently across individuals, it has long resisted simple explanations. For years, scientists debated whether depression or mania was the primary driver of the illness, or whether bipolar disorder should even be considered a single condition at all. The new genetic research suggests the answer may have been hiding in plain sight.

A Massive Genetic Study Changes the Conversation

Researchers recently examined genetic data from more than 600,000 people, including over 27,000 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Instead of treating bipolar disorder as one unified diagnosis, the researchers took a more nuanced approach. They separated the genetic markers associated with major depressive disorder from those linked specifically to manic symptoms.

When they analyzed the results, the imbalance was striking. After removing the genetic signals tied to depression, the researchers found that mania accounted for approximately 81.5 percent of bipolar disorder’s genetic architecture. Depression, by contrast, accounted for just 18.5 percent.

This suggests that bipolar disorder is not genetically split down the middle between two opposing poles. Instead, mania appears to be the dominant biological force shaping the condition.

Why This Finding Matters So Much

This discovery helps explain several long standing mysteries surrounding bipolar disorder. One of the most significant is why the condition is so frequently misdiagnosed, especially in its early stages.

Many people with bipolar disorder first seek medical help during depressive episodes. Depression is painful, disabling, and often frightening, making it more likely to bring someone to a doctor’s office. Manic symptoms, especially hypomania, can feel productive, creative, or even desirable at first, making them less likely to be reported or recognized as a problem.

If mania is the primary genetic driver of bipolar disorder, but depression is often the most visible early symptom, misdiagnosis becomes almost inevitable.

The Overlap With Other Mental Illnesses

Bipolar disorder has long been known to overlap with other psychiatric conditions, particularly major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Patients are sometimes diagnosed with one condition for years before a more accurate diagnosis is made.

The new genetic findings offer a possible explanation. If mania shares genetic roots with traits seen in schizophrenia, such as psychosis or disorganized thinking, it makes sense that the boundaries between these diagnoses can blur. Meanwhile, depressive episodes can closely resemble unipolar depression, further complicating the diagnostic picture.

Understanding that mania plays a dominant genetic role could help clinicians look more carefully for subtle manic traits early on, even when depression appears to be the main issue.

The Genes Behind Mania

The study identified 71 genetic variants strongly associated with manic symptoms, including 18 that had never before been linked to bipolar disorder. Many of these variants are tied to traits that closely resemble classic features of mania.

These traits include a reduced need for sleep, elevated or expansive mood, increased physical activity, night owl tendencies, and impulsive behaviors such as speeding or risk taking.

One surprising finding was what these genes were not strongly linked to. Despite common assumptions, the mania related genetic variants showed weaker connections to substance dependence and risky sexual behavior. This suggests that some behaviors often associated with bipolar disorder may not be driven directly by mania itself, but instead shaped by environmental, social, or situational factors.

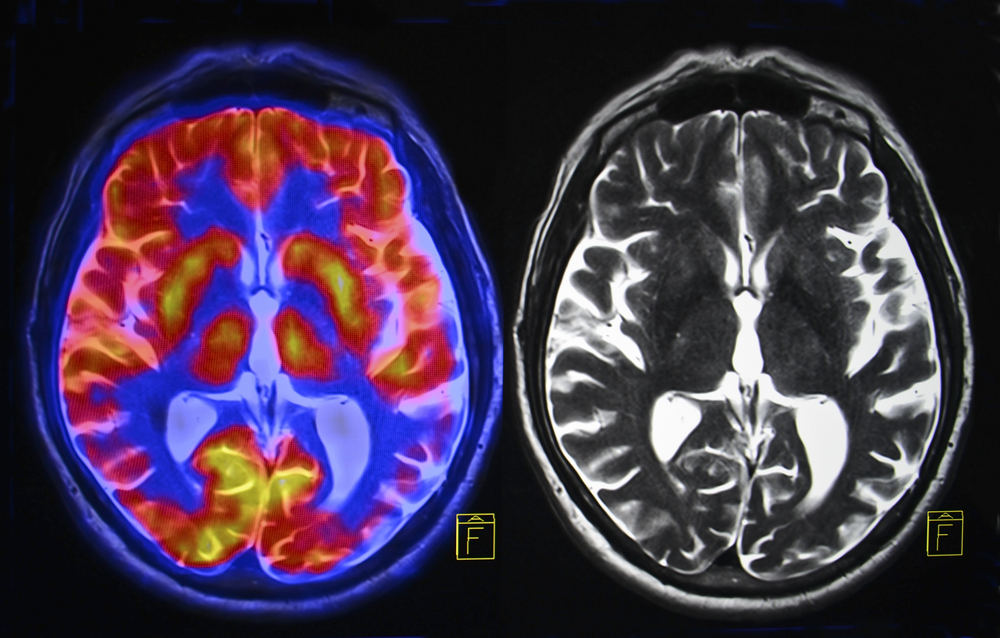

What Is Happening Inside the Brain

Beyond identifying genetic patterns, researchers also explored how these genes affect brain function. Several of the newly identified variants influence calcium channels, which play a critical role in how neurons communicate with one another.

Calcium channels help regulate the flow of electrical signals in the brain. When they do not function properly, communication between brain cells can become unstable, potentially contributing to mood dysregulation, heightened energy, and emotional intensity.

This finding is especially promising because calcium channels are already known targets for some medications. A better understanding of how these channels function in people with bipolar disorder could open the door to treatments that are more precise and more effective.

Bipolar Disorder Is Not Caused by a Single Gene

Despite the significance of these findings, researchers are careful to emphasize that bipolar disorder is not caused by one gene or even a handful of genes. Instead, it appears to arise from the combined effects of many small genetic variations, each contributing a modest amount of risk.

This helps explain why bipolar disorder can look so different from one person to another. It also explains why the condition tends to run in families without following a simple inheritance pattern.

Twin studies provide strong evidence for this complexity. If one identical twin has bipolar disorder, the likelihood that the other twin will also have it is estimated to be between 40 and 70 percent. For fraternal twins, that number drops to around 5 to 10 percent.

Genes create vulnerability, not destiny.

The Role of Neurotransmitters

For years, scientists have focused on neurotransmitters as a possible cause of bipolar disorder. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine play a central role in regulating mood, energy, and motivation.

Research suggests that bipolar disorder may involve imbalances in these chemicals or changes in how sensitive brain cells are to them. Rather than having too much or too little of a single neurotransmitter, the problem may lie in how these systems interact with one another.

Medications that alter neurotransmitter activity, including mood stabilizers and antipsychotics, can help manage symptoms, further supporting the idea that these chemical systems are involved.

Stress as a Trigger, Not a Cause

While genetics lay the groundwork for bipolar disorder, life experiences often determine when and how the condition emerges. Most researchers now support a stress vulnerability model, sometimes called the diathesis stress model.

According to this framework, individuals are born with certain biological vulnerabilities. Stressful life events can activate those vulnerabilities, triggering the first mood episode. Once the cycle begins, biological and psychological processes may help sustain the illness.

Stress can take many forms, from major life events like the loss of a loved one or a job, to more subtle pressures such as chronic sleep deprivation or ongoing conflict. Importantly, stress is highly subjective. What feels overwhelming to one person may be manageable to another.

Triggers for Depressive Episodes

After the onset of bipolar disorder, even relatively small stressors can trigger depressive episodes. Common triggers include disrupted sleep, ongoing stress, physical illness or injury, hormonal changes, lack of exercise, and significant life transitions.

These triggers do not cause bipolar disorder, but they can influence when and how symptoms appear.

Triggers for Manic and Hypomanic Episodes

Manic and hypomanic episodes can be triggered by many of the same factors as depression, but some triggers appear to be more specific. Research has identified several experiences that are more likely to precede manic symptoms.

These include falling in love, starting a major creative project, late night socializing, travel that disrupts sleep cycles, recreational stimulant use, loud music, and major life changes that increase excitement or stimulation.

The postpartum period and the use of certain antidepressants have also been linked to an increased risk of manic or hypomanic episodes in vulnerable individuals.

Why Treatment Has Been So Difficult

Lithium has been used for decades as a primary treatment for bipolar disorder, and it remains highly effective for many people. However, not everyone responds well to lithium, and some experience side effects that make it difficult to tolerate.

Earlier genetic research identified a gene called DGKH, which produces an enzyme involved in a biochemical pathway affected by lithium. This discovery suggested that lithium works closer to the surface of a much larger biological system.

By targeting genes or enzymes further upstream in this pathway, scientists hope to develop medications that are more effective and better tolerated. This approach could eventually allow treatments to be tailored to an individual’s unique genetic profile.

What This Means for Diagnosis

If mania is indeed the dominant genetic driver of bipolar disorder, this could have major implications for diagnosis. Clinicians may need to place greater emphasis on identifying subtle manic traits, even in patients who primarily present with depression.

Earlier recognition of bipolar disorder could reduce years of ineffective treatment and help prevent antidepressant induced manic episodes. It could also lead to more appropriate treatment plans from the very beginning.

Reducing Stigma Through Science

One of the most powerful aspects of this research is its potential to reduce stigma. Bipolar disorder is often misunderstood as a character flaw or a failure of emotional control. Genetic and neurobiological findings make it clear that this is not the case.

Bipolar disorder is a brain based condition shaped by biology, environment, and lived experience. Understanding its roots can foster empathy, patience, and more compassionate care.

A Clearer Picture, Not a Final Answer

While this research marks a major step forward, it does not provide all the answers. Bipolar disorder remains a complex condition influenced by countless factors, many of which are still being uncovered.

Science rarely advances through sudden breakthroughs alone. More often, progress comes from refining our understanding, piece by piece. By identifying mania as the central genetic force behind bipolar disorder, researchers have brought much needed clarity to a field that has long struggled with overlap and uncertainty.

With continued research, investment, and collaboration, these insights could translate into better treatments, earlier diagnoses, and improved quality of life for millions of people around the world.

For those living with bipolar disorder, the message is not that science has finally solved everything. It is that the picture is becoming clearer, and with clarity comes hope.

Loading...