Researchers Transform LSD Into a Powerful Brain Repair Drug

For most of modern history, LSD has been treated as either a cultural lightning rod or a forbidden scientific curiosity. To some, it symbolized the excesses of the counterculture. To others, it represented a dangerous compound capable of destabilizing the mind. Yet beneath decades of controversy, neuroscience has quietly been uncovering something far more interesting about psychedelic molecules. They do not just alter perception. They fundamentally change how the brain grows, adapts, and repairs itself.

Now, researchers may have taken that insight one step further. By subtly altering the molecular structure of LSD, scientists have created a compound that appears to stimulate profound brain healing without inducing hallucinations. The new molecule, known as (+)-JRT, promotes neuroplasticity, restores damaged neural connections, and improves behaviors associated with depression and schizophrenia in animal models, all while avoiding the risks that make psychedelics unsuitable for many patients.

The findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that psychedelics may never have been the final medicine. Instead, they may be the blueprint. What emerges from this research is not just a promising drug candidate, but a deeper shift in how science understands mental illness, consciousness, and the biological roots of healing.

This is the story of how two atoms were moved, and how that small adjustment may change the future of mental health treatment.

The Long-Standing Limits of Psychiatric Medicine

Psychiatric drugs have saved lives. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers have helped millions manage symptoms that once made daily life impossible. Yet even with these advances, psychiatry has struggled with a persistent problem. Most medications treat symptoms without repairing the underlying damage in the brain.

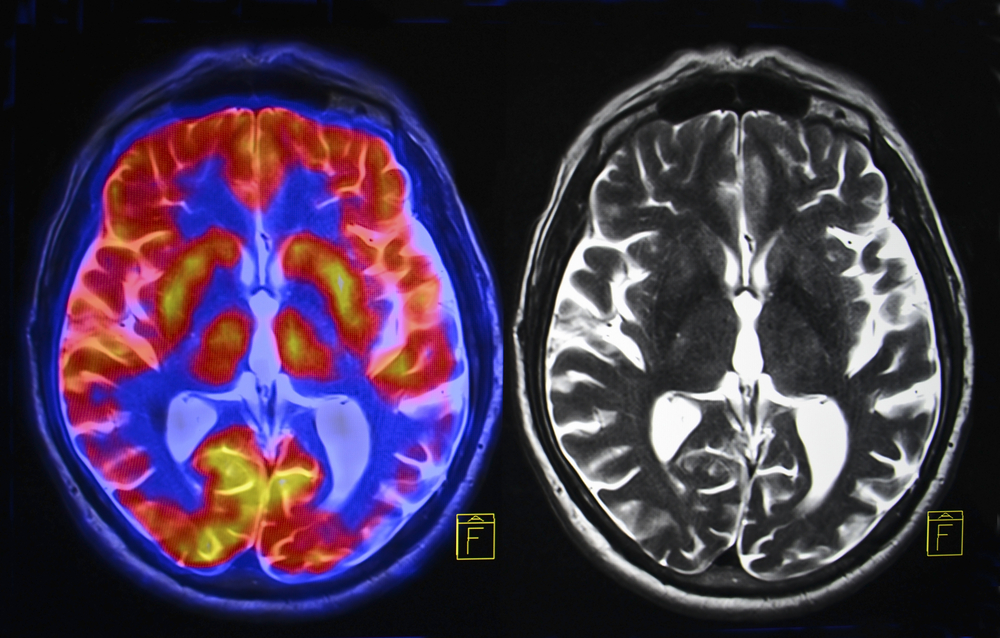

In conditions such as schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, addiction, and chronic stress related illnesses, researchers consistently observe structural changes in the brain. These include reduced dendritic spine density, fewer synapses, and shrinkage in key cortical regions involved in decision making, emotional regulation, and social behavior. These are not abstract concepts. Dendritic spines are the small protrusions that allow neurons to communicate. Fewer spines mean weaker networks and diminished cognitive flexibility.

Traditional antipsychotic medications primarily target dopamine signaling. While this can reduce hallucinations and delusions, it often does little to address negative symptoms such as emotional flatness, lack of motivation, and social withdrawal. Cognitive impairment also tends to persist, leaving many patients functionally limited even when their most severe symptoms are controlled.

Clozapine remains one of the few medications that can improve some of these deficits, but it comes with significant side effects including sedation, metabolic issues, and cognitive dulling. As a result, it is often reserved as a last resort.

The core issue is that most psychiatric drugs manage neural signaling in the moment. Very few help the brain rebuild what has been lost.

Psychedelics and the Discovery of Neuroplasticity

Over the past decade, psychedelics have reentered scientific research under controlled conditions. What researchers found challenged long held assumptions. Substances like LSD, psilocybin, and DMT were not simply causing temporary hallucinations. They were triggering lasting changes in brain structure.

At the cellular level, psychedelics strongly promote neuroplasticity. They increase dendritic spine growth, enhance synapse formation, and strengthen neural circuits in the cortex. These changes can persist long after the subjective effects wear off.

This discovery reframed psychedelics from recreational curiosities into powerful tools for understanding how the brain adapts and heals. In animal studies and early human trials, psychedelic compounds showed promise in treating depression, PTSD, addiction, and end of life anxiety.

But a major barrier remained. Psychedelics activate serotonin receptors in a way that can destabilize perception and cognition. For individuals with psychotic disorders or a genetic vulnerability to psychosis, these effects pose serious risks. As a result, most clinical trials exclude up to 90 percent of potential patients.

This created a paradox. Psychedelics appeared uniquely capable of repairing damaged neural circuits, yet they were unsafe for many of the people who might benefit most.

A Subtle Molecular Shift With Profound Consequences

At the University of California, Davis, a research team began exploring whether the therapeutic properties of LSD could be separated from its hallucinogenic effects. The work was led by David E. Olson, director of the Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics.

Instead of asking whether LSD could be safely administered, the team asked a more fundamental question. What exactly in the molecule produces hallucinations, and what produces neural growth?

The answer led them to a remarkably simple experiment. They took LSD and swapped the position of two atoms in its molecular structure. This change did not alter the molecule’s weight or overall shape. It did not even change how it initially fit into certain receptors. Yet it dramatically altered how the compound behaved in the brain.

The new molecule was named (+)-JRT, after Jeremy R. Tuck, the graduate student who first synthesized it. The process took nearly five years and required a twelve step chemical synthesis. But the result was striking. JRT looked almost identical to LSD on paper, yet its effects could not have been more different.

How JRT Interacts With the Brain

To understand why JRT works, it helps to look at serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A receptor. This receptor plays a central role in both psychedelic experiences and neuroplasticity. Full activation of 5-HT2A is associated with hallucinations and altered perception. Partial activation, however, appears sufficient to stimulate neuronal growth.

JRT binds selectively to 5-HT2A receptors, but it activates them in a more controlled way. It also shows strong activity at 5-HT2C receptors, which are associated with antidepressant and antipsychotic effects without heavy dopamine disruption.

In laboratory studies, JRT demonstrated several key properties:

- It promoted robust growth of dendritic spines in cortical neurons

- It increased synapse density in the prefrontal cortex

- It did not induce hallucinogenic behaviors in animal models

- It did not trigger gene expression patterns linked to psychosis

In mice, a single dose of JRT increased dendritic spine density by 46 percent and synapse density by 18 percent in the prefrontal cortex. These are not marginal improvements. They suggest real structural restoration in regions associated with cognition and emotional regulation.

Importantly, animals treated with JRT did not display the head twitch responses or hyperactivity typically seen with hallucinogens. On a genetic level, JRT also avoided activating pathways associated with schizophrenia.

Implications for Schizophrenia Treatment

Schizophrenia remains one of the most challenging psychiatric disorders to treat. While positive symptoms such as hallucinations can often be controlled, negative and cognitive symptoms are far more resistant. These include reduced motivation, emotional blunting, impaired working memory, and difficulty adapting to new information.

In mouse models designed to mimic aspects of schizophrenia, JRT produced significant improvements. Treated animals showed enhanced cognitive flexibility and improved performance in tasks related to learning and adaptation. Crucially, these benefits occurred without worsening behaviors associated with psychosis.

This positions JRT as something fundamentally different from existing antipsychotics. Rather than suppressing neural activity, it appears to rebuild the neural architecture itself.

If these effects translate to humans, JRT could address the aspects of schizophrenia that most impair quality of life. It may also reduce reliance on medications that carry heavy side effects.

A Surprising Antidepressant Effect

One of the most unexpected findings emerged when researchers tested JRT in models of depression. The compound produced rapid and robust antidepressant like effects. Even more striking, it was approximately 100 times more potent than ketamine, which is currently one of the most effective fast acting antidepressants available.

Ketamine works in part by promoting synaptic growth, but it also causes dissociation and carries a risk of abuse. JRT achieved similar or greater benefits at much lower doses without inducing dissociative behaviors.

In stressed animals, JRT reversed cortical atrophy and restored normal behavioral patterns. This suggests that its antidepressant effects are not merely symptomatic. They may stem from actual repair of stress damaged brain circuits.

Beyond Hallucinations: Redefining Psychedelic Medicine

JRT belongs to a growing class of compounds known as psychoplastogens. These are molecules that rapidly promote neural plasticity and structural remodeling. What sets JRT apart is its ability to do so without altering perception.

This challenges a long held assumption that the psychedelic experience itself is necessary for healing. While subjective experiences may play a role in therapy, the biology tells a deeper story. The brain appears capable of entering a growth oriented state without consciousness being dramatically altered.

From a scientific perspective, this is a paradigm shift. Psychedelics are no longer just experiential tools. They are molecular scaffolds that can be refined and optimized.

Bridging Neuroscience and Consciousness

From a broader perspective, this research invites reflection on the relationship between consciousness and biology. For thousands of years, cultures around the world have used altered states to facilitate healing, insight, and transformation. Modern neuroscience now shows that these states coincide with heightened plasticity and network flexibility in the brain.

JRT suggests that the healing component may not be the visions themselves, but the temporary loosening of rigid neural patterns. The subjective experience may be one expression of that process, but not its only form.

This does not diminish the value of psychedelic experiences. Instead, it expands the landscape. Healing can occur quietly, at the molecular level, without dramatic shifts in perception.

Safety, Ethics, and the Road Ahead

Despite the excitement, it is important to remain grounded. JRT has not yet been tested in humans. Animal models are informative, but they cannot capture the full complexity of human consciousness and psychiatric illness.

Before JRT can become a medication, it must undergo extensive safety testing and clinical trials. Researchers are currently refining its synthesis and testing related analogues that may be even more effective.

Still, the implications are profound. If successful, JRT could expand access to neuroplastic therapies for populations currently excluded from psychedelic research. This includes individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and a family history of psychosis.

It also raises ethical questions about how such powerful tools should be used. Enhancing neuroplasticity could have wide ranging effects on identity, learning, and emotional processing. Careful oversight will be essential.

A Glimpse Into the Future of Mental Health

What makes this discovery so compelling is not just the promise of a single drug, but the method behind it. By understanding how molecules interact with receptors at a fine grained level, scientists can design medicines that work with the brain rather than against it.

This approach represents a shift away from blunt force pharmacology toward precision neuroscience. Instead of suppressing symptoms, future treatments may restore the brain’s natural capacity to adapt and heal.

In a sense, LSD has come full circle. Once feared for its ability to dissolve boundaries, it is now inspiring medicines that may help rebuild them where they have been lost.

All because two atoms were moved, and a new way of thinking emerged.

If the early promise of JRT holds true, the next generation of psychiatric medicine may not be defined by sedation or suppression, but by growth, flexibility, and repair. And that could change how we understand not only mental illness, but the brain itself.

Loading...