The Bear That Waited Thousands of Years for the Truth to Catch Up

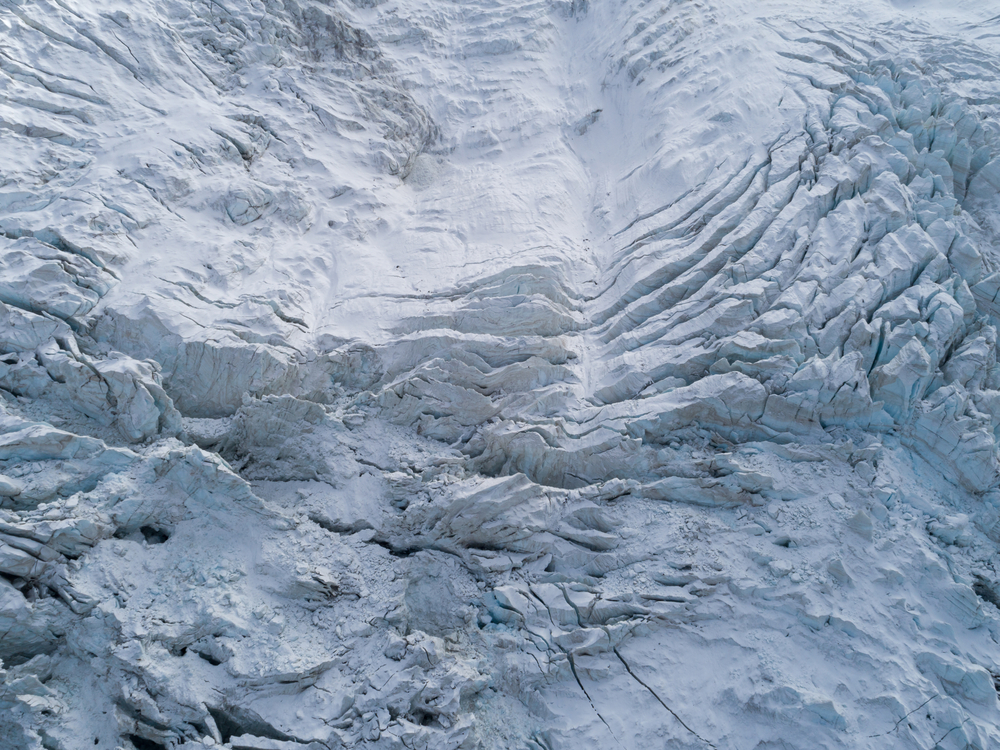

For most of human history, the frozen ground of the far north acted like a locked archive. Animals lived, died, and disappeared beneath layers of ice long before anyone could study them. Now that archive is beginning to open. As Arctic ground warms, things that were never meant to be seen again are surfacing almost intact, forcing scientists to confront moments from the deep past with an immediacy that feels almost unsettling.

One of those moments arrived when a bear emerged from the Siberian permafrost in extraordinary condition. At first glance, it seemed to rewrite what scientists thought was even possible. But the real significance did not come from the shock of the discovery alone. It came from what happened next, as early assumptions gave way to deeper analysis and a far more revealing story. What surfaced was not just an ancient animal, but a reminder that discovery does not end when something is found. It begins when we slow down and let the evidence speak.

Where Time Stands Still Long Enough to Be Studied

Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island sits far from major cities and even farther from routine scientific work. Part of the Lyakhovsky Islands in the East Siberian Sea, it is a place where the ground stays frozen year after year, locking biological material in place before decay can fully take hold. In environments like this, death does not immediately lead to disappearance. Instead, bodies can remain sealed in ice and sediment, preserving details that would vanish almost anywhere else. That frozen stability is what makes this location so important, because it allows scientists to study entire organisms rather than fragments and fossils.

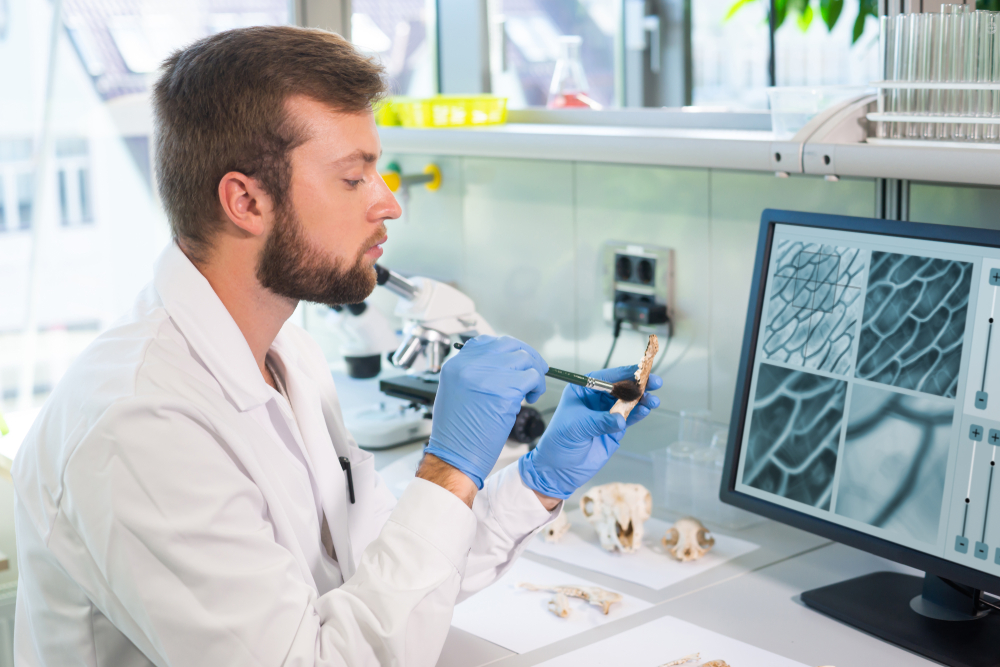

The discovery itself did not begin with a research expedition. Reindeer herders moving across the island were the first to encounter the exposed carcass and recognized that it was something unusual. They contacted researchers at North Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, who quickly realized that the bear’s condition was extraordinary. The animal still had its skin and fur, along with a preserved nose, teeth, claws, body fat, and internal organs. Preservation at this level immediately suggested great age and pointed toward an extinct species rather than a modern animal that had died recently.

When scientists examined the carcass in 2020, the most logical explanation was that it belonged to a cave bear, Ursus spelaeus. Cave bears lived during the last Ice Age, went extinct roughly twenty two thousand years ago, and were closely related to brown and polar bears while being much larger than any bear alive today. Early estimates placed the age of the remains between twenty two thousand and nearly forty thousand years old, which would have made this the first fully preserved cave bear ever discovered. In a press release announcing the find, NEFU researcher Lena Grigorieva said, “This is the first and only find of its kind , a whole bear carcass with soft tissues.” At that point, the interpretation matched what the evidence appeared to show, even though later analysis would complicate that initial picture.

When the Evidence Refused to Cooperate

As researchers spent more time with the remains, the initial story began to feel less settled. Details that once seemed to confirm an Ice Age origin started raising quiet questions instead. Measurements, anatomy, and closer inspection suggested proportions that did not fully match what scientists knew about cave bears. The deeper they looked, the more the discovery resisted its original label.

Further analysis brought a clear shift in understanding. The animal was not an extinct cave bear at all, but a brown bear (Ursus arctos), a species still living today. Dating results showed that the bear had lived far more recently than first assumed. According to a statement released by the NEFU research team in December 2022, the remains were approximately three thousand four hundred and sixty years old. Ancient, yes, but not a survivor from the last Ice Age. To reflect both its identity and its place of discovery, researchers named it the Etherican bear after the nearby Bolshoy Etherican River.

This change did not weaken the importance of the find. It strengthened it. The reclassification revealed how extreme preservation can blur the line between deep prehistory and more recent past, especially in environments where cold slows decay almost to a halt. What initially appeared to be a once in a lifetime Ice Age relic became something equally valuable: a rare, intact snapshot of a brown bear from the mid Holocene, preserved so well that it briefly convinced experts they were looking tens of thousands of years further back in time.

What the Body Itself Revealed

Once researchers looked beyond labels and timelines, the bear’s body began to tell its own story. The necropsy made it possible to assess real physiological condition rather than rely on inference. Preserved muscles, connective tissue, and organs showed an animal that had not been weakened by long term illness or starvation. Fat stores and muscle tone pointed to a young bear that had been eating well and maintaining strength up to the point of death.

The most telling evidence came from the spine. Severe trauma would have drastically limited movement and made survival unlikely, pointing to a sudden fatal event rather than gradual decline. This finding helped rule out slow environmental stress as the primary cause and shifted attention toward an abrupt injury that ended the bear’s life.

Beyond immediate conclusions, the necropsy created lasting scientific value. Tissue samples were preserved for future cellular and biochemical analysis, allowing researchers to study how living structures endure after thousands of years in frozen ground. In rare cases like this, a body does more than confirm a cause of death. It preserves a moment in time with a level of biological detail that almost never survives.

When the Past Has No Time to Wait

Discoveries like this are not only rare, they are fragile the moment they appear. Once frozen remains rise to the surface, preservation is no longer guaranteed. Air, moisture, and shifting temperatures begin to work immediately, undoing in days what took thousands of years to protect. What was once sealed safely underground becomes vulnerable the instant it is exposed.

This changes how science must respond. Researchers are no longer studying history at a comfortable distance. They are forced to act quickly, often in isolated regions with limited infrastructure, where every decision carries weight. Recovery, transport, and storage must be carefully coordinated, because hesitation can mean irreversible loss of biological detail. In these moments, restraint becomes as important as curiosity.

The bear’s emergence reflects a larger reality. The past is no longer waiting quietly beneath the surface. It is arriving unexpectedly and without patience. Whether these stories endure now depends not only on what is found, but on how quickly and carefully humans respond when the ground finally lets go of what it has been holding.

The Danger of Wanting Answers Too Quickly

There is a quiet pressure in discovery to name things as fast as possible. Labels make the unknown feel manageable. They give stories a headline and conclusions a sense of finality. But this bear shows how easily certainty can outrun understanding when something looks extraordinary at first glance. The mind wants resolution before the evidence has finished speaking.

In moments like these, restraint becomes a skill. Science is not only about what can be identified, but about what must remain open until enough information exists. Early conclusions are not failures, but they become fragile when they harden too soon. The strength of this discovery lies in the willingness to pause, revisit assumptions, and accept that initial impressions may be incomplete or misleading.

This lesson reaches beyond the Arctic. In a world that rewards speed and certainty, the bear reminds us that truth often unfolds more slowly. What matters is not how fast an answer arrives, but whether it can withstand closer scrutiny. Sometimes the most meaningful discoveries are not the ones that confirm what we expect, but the ones that force us to stay curious a little longer.

What the Ice Gave Back

This bear matters not because it was intact, but because it forced a pause. It surfaced carrying enough detail to resist easy conclusions and enough silence to demand careful attention. What it offered was not an instant answer, but an opportunity to slow down and let evidence shape understanding rather than expectation.

The real power of this discovery lies in what happened after the excitement faded. Assumptions were tested, corrected, and refined, not to protect a narrative, but to protect accuracy. In that shift, the find became more than a scientific event. It became proof that patience is not a weakness in discovery, but its foundation.

As frozen ground continues to open, more stories will rise with similar urgency. The challenge ahead is not whether we can uncover them, but whether we can meet them with humility. Some truths survive thousands of years only to remind us that understanding is earned by listening longer than we are comfortable with.

Featured Image from Shutterstock

Loading...