What Buddhist Monks Knew About Your Brain Before Scientists Did

For thousands of years, Buddhist monks sat in silence, observing their own minds. What they discovered in those quiet hours might strike modern readers as strange, even unsettling. Yet scientists working in sterile labs with brain-scanning machines now arrive at similar conclusions through entirely different paths.

Something profound connects ancient monasteries to modern research facilities. And that connection might change how you see yourself, your past, and your future.

Evan Thompson, a philosophy of mind professor at the University of British Columbia, has spent years studying where Eastern contemplative traditions meet Western cognitive science. His findings suggest that monks understood something about human consciousness that took neuroscientists millennia to catch up with.

But before we explore what they found, consider a question. Who were you ten years ago? Five years ago? Yesterday? Most people assume an invisible thread runs through all those versions, a core identity that persists through time. What if that assumption is wrong?

Your Brain Never Sits Still

Picture your brain as you read these words. Neurons fire in patterns, electrochemical signals race along pathways, and regions light up in response to each sentence. None of it holds still. Every millisecond brings new activity, new configurations, new states.

Neuroscientists studying self-awareness expected to find a control center somewhere in the brain, a region that houses “you.” A paper published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences delivered a surprise. Self-processing does not live in any single region or network. Instead, it spreads across a broad range of neural processes that shift and change without pause. No fixed address exists for the self because the self, as we imagine it, may not be a fixed thing at all.

Buddhist philosophy arrived at this idea through a different route. Monks practicing deep meditation noticed that when they searched for a permanent self, they found only change. Thoughts arose and faded. Emotions appeared and dissolved. Sensations came and went. Nothing stayed.

They called this teaching “anatta,” which translates as “not-self” or “non-self.” It does not mean you do not exist. Rather, it suggests that what you call “self” behaves more like a river than a rock. A river keeps its name even as new water flows through it every second. Your sense of identity works the same way.

Thompson puts it in terms that bridge both worlds. “Buddhists argue that nothing is constant, everything changes through time, you have a constantly changing stream of consciousness,” he explains. “And from a neuroscience perspective, the brain and body is constantly in flux. There’s nothing that corresponds to the sense that there’s an unchanging self.”

You Are Not Who You Were at Age Three

Close your eyes and think back to your earliest memory. Maybe you recall a birthday party, a family trip, or the face of someone who cared for you. That small child in your memory carries your name. You assume, without question, that some essential core of that child persists inside you now. But what if you examined that assumption more closely?

Every cell in your body has been replaced multiple times since then. Your brain has rewired itself countless times in response to new experiences. Your beliefs have shifted. Your fears have changed. Your understanding of the world bears little resemblance to what it was at age three. So what, exactly, connects that child to the adult reading these words?

Buddhists would say the connection is a story, a narrative your mind constructs to create a sense of continuity. That story serves a purpose. It helps you function in the world, plan for the future, and learn from the past. But the story is not the same as a fixed, unchanging essence.

Neuroscience supports this view. Memory itself is not a recording that plays back exactly as events happened. Each time you recall a memory, your brain reconstructs it, and small changes creep in. Your memories of being three years old are not snapshots. They are recreations, shaped by everything you have experienced since then.

If your memories change, your cells replace themselves, and your brain rewires with each new experience, where does the permanent self hide? Both ancient wisdom and modern science suggest the same answer. It does not.

Why a Shifting Self Sets You Free

At first, the idea of no fixed self might feel frightening. People cling to identity because it provides safety. Knowing who you are gives you ground to stand on. But consider the freedom that comes with letting go of that fixed idea.

If you believe you are anxious by nature, you might never try meditation because “that’s just not who I am.” If you believe you are bad at math, you might avoid career paths that could bring you joy. If you believe you are the person who failed at relationships in your twenties, you might sabotage connections in your thirties. All of these limits depend on a fixed self. Remove the fixed self, and the limits dissolve.

Neuroplasticity offers scientific backing for this freedom. Your brain can change at any age. Neural pathways that support old habits can weaken while new pathways grow stronger. People can learn new skills, adopt new mindsets, and become different versions of themselves.

Buddhist monks understood this through practice. They trained their minds through meditation and saw direct results. A person prone to anger could cultivate patience. A person trapped by craving could find contentment. A person lost in confusion could gain clarity.

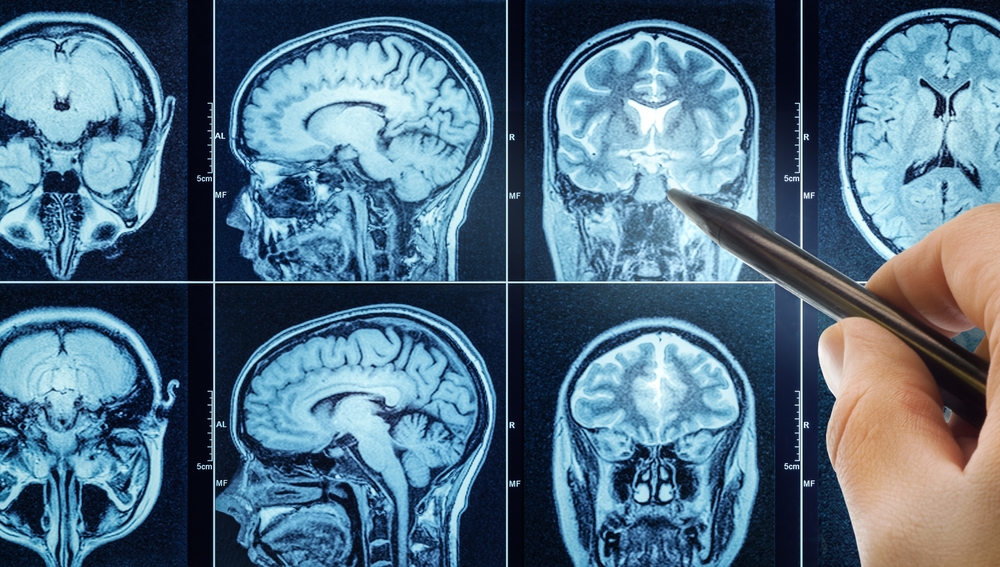

Modern brain imaging confirms what monks reported. Regular meditation practice produces measurable changes in brain structure and function. Areas linked to emotional regulation grow denser. Activity in regions associated with stress decreases. Mental training works.

If nothing about you stays fixed, then nothing about your future stays predetermined. Each day offers raw material for something new.

Meditation Rewires More Than Mood

Scientists once believed the adult brain was set in stone. After childhood, they thought, the basic structure held firm and only declined with age. That view has crumbled.

Studies of meditators show changes in gray matter, alterations in connectivity between brain regions, and shifts in baseline activity patterns. Long-term practitioners display brains that function differently from those of non-meditators.

But the benefits extend beyond mood improvement or stress reduction. Cognitive abilities themselves appear trainable through mental practice. Attention can sharpen. Working memory can expand. Emotional responses can become more regulated.

Monks did not need brain scanners to know this. They observed the changes in themselves and in their students over the years of practice. Science has caught up to verify what contemplatives long claimed.

What matters most is the implication. If the brain can change, and if the self is nothing more than a pattern the brain creates, then you hold more power over your own identity than you might have believed.

Awareness in Deep Sleep

One of the stranger claims in Buddhist and Indian philosophy involves consciousness during dreamless sleep. Common sense says you disappear during deep sleep. You lie unconscious until dreams begin or morning arrives.

Thompson describes the standard scientific view and its alternative. “The standard neuroscience view is that deep sleep is a blackout state where consciousness disappears,” he notes. “In Indian philosophy we see some theorists argue that there’s a subtle awareness that continues to be present in dreamless sleep, there’s just a lack of ability to consolidate that in a moment-to-moment way in memory.”

A study published in 2013 tested this idea by examining meditators’ brain activity during sleep. What researchers found suggested that trained meditators might maintain some capacity for awareness even in states where most people go blank. Their brains showed patterns indicating information processing at levels that should not occur during deep sleep.

Whether consciousness truly persists through dreamless sleep remains an open question. But the fact that science takes the question seriously shows how much the field has changed. Ideas that once seemed like mystical speculation now receive rigorous investigation.

Where Science and Spirituality Still Part Ways

Honest disagreement remains between neuroscience and Buddhist philosophy on certain points. Many Buddhists believe in some form of consciousness that can exist independent of a physical body. Some traditions teach that awareness carries forward after death, continuing in new forms.

Neuroscientists, including Thompson, do not accept this claim. For them, consciousness depends on the brain. No brain, no awareness. Neither side has proven its case beyond doubt. Science cannot yet explain how physical processes in the brain give rise to the subjective experience of being aware. And Buddhist claims about consciousness beyond the body remain beyond the reach of current scientific methods.

Both sides benefit from acknowledging what they do not know. Certainty on questions this deep may never arrive. What matters is that two very different traditions, working with very different methods, have converged on important truths about the nature of self.

A Construction, Not a Con

Some scientists have argued that because the brain constructs the self, the self must be an illusion. If something is built rather than found, the reasoning goes, it cannot be real.

Thompson pushes back against this logic. “In neuroscience, you’ll often come across people who say the self is an illusion created by the brain,” he observes. “My view is that the brain and the body work together in the context of our physical environment to create a sense of self. And it’s misguided to say that just because it’s a construction, it’s an illusion.”

A house is a construction, but you can still live in it. A marriage is a construction, but it still shapes your life. A career, a friendship, and a community all require building. None of them is less real because human effort created them.

Your self operates the same way. Yes, your brain builds it. Yes, it changes over time. Yes, it depends on your body, your environment, and your relationships. None of that makes it fake.

What it does mean is that you have more influence over your own identity than you might have assumed. If the self is an ongoing project rather than a finished product, then you remain, in some sense, the architect of who you become.

A New Chance Every Day

Monks have known for centuries what labs now confirm. You are not a fixed entity moving through time. You are a process, a pattern, a river that keeps flowing.

Some find this unsettling. Letting go of the solid self feels like losing something precious.

But look at what you gain. Freedom from old stories that no longer serve you. Permission to grow in directions you never imagined. Release from the prison of believing you must remain who you have always been.

Each morning, you wake up as a slightly different version of yourself. Each experience rewires your brain in small ways. Each choice shapes the pattern that will become tomorrow’s self.

Science and ancient wisdom agree on the essential point. You are not trapped. You are not finished. And the self you will become remains, in every meaningful sense, up to you.

Loading...