Experts Issue Warning as Infected ‘Zombie’ Squirrels Covered in Warts Spotted in the Us

Every neighborhood has its regulars. The jogger who passes at dawn, the mail carrier with a familiar wave, and, of course, the squirrels those tiny daredevils racing along fences, tumbling through branches, and stealing seeds from bird feeders with unapologetic charm. They’re part of the background music of our lives, so ordinary that we hardly notice them.

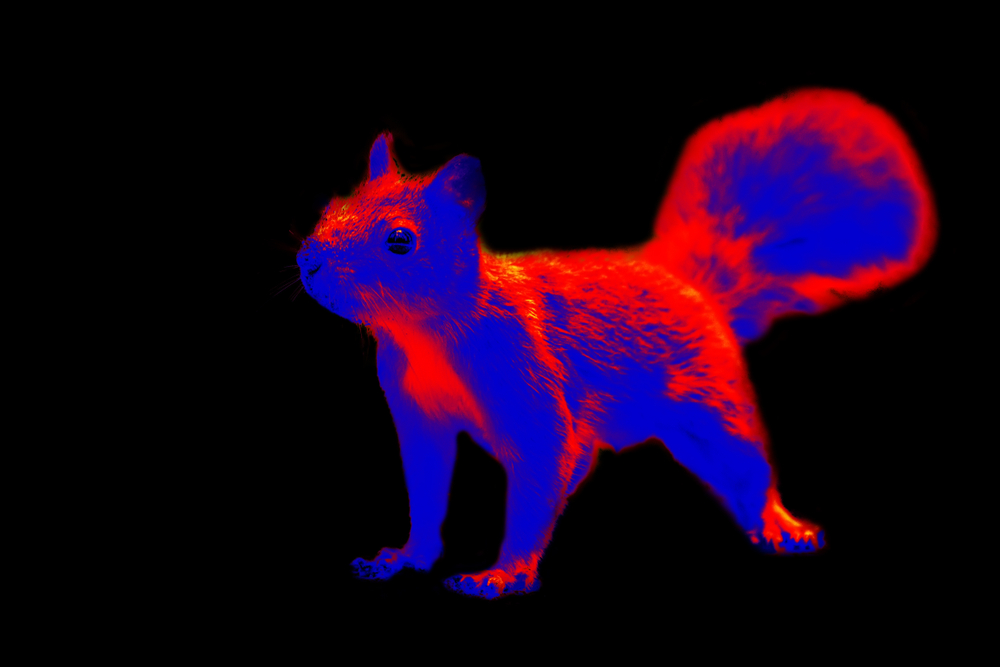

But imagine stepping into your yard one morning and freezing in place. The squirrel you expected to see leaping effortlessly across the grass is instead limping, its fur patchy, its body disfigured by swollen, oozing growths. Its once-bright eyes are shadowed by tumors. It doesn’t look like the playful trickster you’ve always known. It looks like something out of a horror film.

That’s the unsettling reality many homeowners across the U.S. and Canada have faced in recent years. The internet dubbed them “zombie squirrels” grotesque, wart-covered creatures that seem less like nature’s survivors and more like a warning sign of something gone terribly wrong. Photos and videos of these stricken animals have spread across social media, sparking everything from shock and disgust to compassion and curiosity.

When Familiar Becomes Unfamiliar

For decades, the gray squirrel has been a symbol of everyday life in North America playful, mischievous, sometimes a nuisance, but rarely a cause for fear. We expect them to chatter from treetops, raid bird feeders with acrobatic flair, and vanish in a blur of tails at the faintest sound. That familiarity makes them comforting, almost like neighbors who never move away.

So when residents across Maine, the Midwest, and Canada began spotting squirrels with hairless patches, bulbous tumors, and oozing sores, the reaction was visceral. What once blended into the rhythm of backyard life now looked alien, almost nightmarish. The contrast was so jarring that the internet gave them a name meant to capture both fascination and horror: “zombie squirrels.”

We had rabbits growing spikes last week and we have “Zombie Squirrels” this week.

— The Facts Dude 🤙🏽 (@The_Facts_Dude) August 18, 2025

Leporipoxvirus is what it’s called. pic.twitter.com/K4lv7R4bAW

The first cases weren’t logged in scientific journals or wildlife reports. They appeared on Reddit threads and local Facebook groups in 2023, shared by confused homeowners wondering whether their eyes were playing tricks on them. One post showed a squirrel with grotesque growths covering half its face, another limped across a lawn covered in lesions. The images spread quickly, tapping into something deeper than curiosity a sense that what we thought we knew about the natural world could no longer be trusted.

This wasn’t just about squirrels. It was about the unease that rises in us when the familiar suddenly looks strange. The backyard acrobat transformed into a stumbling creature of sores. The harmless neighbor turned into a haunting reminder of how fragile normalcy really is.

The Science Behind the ‘Zombie Squirrel’ Phenomenon

Beneath the lurid nickname and unsettling photos, the truth is both less apocalyptic and more fascinating. The “zombie” appearance is caused by a naturally occurring virus known as squirrel fibromatosis, part of the leporipoxvirus family. It is not new, nor is it a threat to humans or pets though it can dramatically alter the way a squirrel looks.

Fibromatosis spreads mainly through direct contact: saliva exchanged when squirrels jostle at a crowded feeder, or virus particles left behind on surfaces where an infected animal has fed. Mosquitoes and other biting insects can also play a role in carrying it from one squirrel to another. Once inside the body, the virus triggers the growth of wart-like fibromas tumors that can appear anywhere: across the face, around the eyes and mouth, along the limbs, and sometimes even on sensitive areas like the genitals.

These growths often ooze or split open, leaving behind raw lesions that look shocking to human eyes. Yet for most gray squirrels, the disease is not fatal. Within four to eight weeks, their immune system typically suppresses the virus, the growths scab over, and the animal recovers with little more than scars to show for the ordeal.

Still, not every squirrel survives. In severe cases, tumors can interfere with basic survival blocking vision, limiting movement, or making it difficult to eat. Those weakened animals may starve or fall prey to predators. But experts emphasize that such outcomes are the exception, not the rule.

It’s also important to distinguish fibromatosis from squirrel pox, a separate virus that has devastated red squirrel populations in the United Kingdom. Unlike fibromatosis, squirrel pox is almost always fatal for red squirrels, leaving conservationists in the UK fighting to protect dwindling populations. By comparison, North America’s gray squirrels, resilient as they are, usually weather fibromatosis outbreaks and rebound.

How Human Behavior Fuels the Spread

Viruses don’t spread in a vacuum they exploit connections. And sometimes, without realizing it, we humans create the very conditions that allow them to thrive. In the case of squirrel fibromatosis, the culprit isn’t just mosquitoes or natural transmission between animals. Much of the spread can be traced back to something as simple, and as well-intentioned, as feeding wildlife.

Backyard bird feeders, beloved by many homeowners, inadvertently become crowded meeting spots for squirrels. Dozens of animals may jostle and nibble from the same source, leaving behind saliva or rubbing lesions against the feeder. One infected squirrel is all it takes for a virus to linger on the seed or surface, waiting to be picked up by the next visitor. As wildlife biologist Shevenell Webb explained, “It’s like when you get a large concentration of people. If someone is sick and it’s something that spreads easily, others are going to catch it.”

The problem is amplified during warmer months. Bird feeders are refilled more often, and squirrels, more active in their foraging, overlap frequently at these communal spots. What might have been a minor illness in an isolated squirrel can ripple outward, touching entire neighborhoods of wildlife in a matter of weeks.

The good news is that small adjustments can make a big difference. Experts recommend:

- Regular cleaning: Disinfecting feeders with a mild bleach solution to kill lingering pathogens.

- Pausing feeding temporarily: If sick squirrels are spotted, taking feeders down for a few weeks to break the cycle.

- Rethinking the setup: Using squirrel-proof feeders or planting native shrubs and berry bushes that provide food for birds without creating artificial crowding zones for squirrels.

These may seem like small gestures, but their impact reaches far beyond the backyard. They remind us of an uncomfortable truth: our choices, however small, ripple through the ecosystems around us. In trying to help, we sometimes harm — but with awareness, those same actions can turn into solutions.

The Role of Social Media in Shaping Fear and Awareness

The phrase “zombie squirrel” didn’t originate in a lab or wildlife report. It was born online. When the first disturbing photos surfaced in 2023 a squirrel with growths covering half its face, another stumbling with tumors along its body they spread quickly through Reddit threads, local Facebook groups, and later, mainstream news outlets. The grotesque imagery caught attention instantly, fueling both fascination and dread.

It’s easy to understand why. We are used to seeing squirrels as energetic, almost comical fixtures of our backyards. To suddenly see them hairless, scarred, and oozing felt like the plot of a post-apocalyptic video game. Memes compared them to creatures from The Last of Us or low-budget horror films. Jokes about a “rodent apocalypse” piled up alongside genuine concern: Is this dangerous? Should we be worried?

Social media thrives on this tension between humor and fear, between curiosity and alarm. On one hand, the amplification of shocking images can stoke panic and misinformation. A few viral posts can transform a local wildlife issue into what feels like a looming global threat. On the other, this digital chorus has become an unlikely early-warning system. Wildlife officials now track online sightings to map the spread of diseases across regions where formal surveillance is limited. A single Reddit post from Maine might alert experts in neighboring states to watch for signs of the same condition.

But perhaps the most telling part of this phenomenon is what it reveals about us. In an age marked by pandemics, superbugs, and headlines of climate-driven diseases, our collective anxiety sits just beneath the surface. When the familiar suddenly looks monstrous, our fear isn’t just about the animal it’s about what that transformation might mean for us.

Lessons from Other ‘Monster’ Wildlife Diseases

The sight of a squirrel disfigured by tumors may seem unique, but nature has a long history of producing creatures that look like they’ve wandered out of a horror story. In northern Colorado, for example, residents reported seeing rabbits with dark, horn-like growths sprouting from their heads and faces. Locals nicknamed them “Frankenstein rabbits.” The culprit was Shope papillomavirus, a disease first identified in the 1930s that causes keratin-based tumors the same protein that makes up human hair and nails.

To the untrained eye, these rabbits looked like monsters. Yet for most of them, the condition was temporary. Their immune systems eventually suppressed the virus, the growths dried up, and the animals returned to normal life. In rare cases, the tumors interfered with eating or vision, and occasionally they turned cancerous. Still, the vast majority survived.

What’s striking is not just the visual shock, but the scientific legacy of this disease. Research on Shope papillomavirus laid the groundwork for understanding how viruses cause tumors in humans. Decades later, that knowledge directly contributed to the development of the HPV vaccine one of the most effective tools we have today in preventing certain types of cancer.

This parallel matters. Just as the grotesque rabbits helped pave the way for breakthroughs in human health, the so-called “zombie squirrels” may also hold lessons. While squirrel fibromatosis is less studied and generally less severe, monitoring outbreaks provides scientists with valuable insights into how viruses spread, how immunity works in wild populations, and how environmental changes from warmer summers to suburban sprawl affect the health of entire ecosystems.

Coexisting With Wildlife Responsibly

When we see an animal in distress, our first instinct is often to intervene. We want to help, to fix, to do something. But with squirrel fibromatosis, experts caution that the most compassionate act is often restraint.

What Not to Do

- Don’t try to capture or treat them. A sick squirrel, no matter how weak it appears, will fight to defend itself. Handling wildlife risks injury to both animal and human.

- Don’t attempt to euthanize them. While their appearance may be shocking, most gray squirrels recover within weeks. Interfering can disrupt the natural healing process and cause needless suffering.

- Don’t let pets corner them. Dogs or cats may not contract the virus, but a bite or scratch from a frightened squirrel can spread other infections.

What You Can Do

- Pause or clean feeders. Since feeders are a primary source of transmission, disinfecting them with a mild bleach solution or removing them for a few weeks if sick squirrels are spotted can help stop the cycle.

- Plant natural food sources. Native shrubs and berry bushes give birds the nourishment they need without crowding squirrels into artificial feeding zones.

- Observe from a distance. Watching wildlife is still possible and often beautiful without interfering in their survival.

- Report unusual cases. Local wildlife agencies often use citizen reports as valuable data, helping them track patterns and outbreaks across regions.

These may seem like small adjustments, but they reflect a larger truth: coexistence requires humility. We share space with creatures whose lives run parallel to ours, whose struggles and recoveries often go unnoticed. When we resist the urge to control, and instead choose to respect, we create healthier environments not only for wildlife but also for ourselves.

When Nature Holds Up a Mirror

The sight of a “zombie squirrel” can be unsettling a familiar creature suddenly rendered strange, a reminder that even in our own neighborhoods, nature carries mysteries we don’t fully understand. Yet the deeper truth is more hopeful than horrifying. These squirrels are not omens of doom. They are survivors. They endure cycles of illness and healing that remind us of nature’s resilience, and of the responsibility we hold as stewards of the spaces we share with them.

The viral images, the headlines, the fears they reveal as much about us as they do about the squirrels. They show how quickly we move to fear what looks different, how fast we label something grotesque, and how easily we forget that life, in all its forms, carries struggle as well as recovery.

So perhaps the lesson is this: just as most squirrels heal from their scars, so too can we. The world is full of things that at first appear broken or frightening, but with time, they often reveal resilience and strength. The challenge is not to recoil in fear, but to notice with respect.

The next time you see a squirrel in your yard, whether bright-eyed or bearing scars, remember that their story is also ours: survival, adaptation, and the quiet beauty of healing, even when it looks ugly at first glance.

Loading...