A Cosmic Butterfly Glows 3,800 Light-Years Away in Breathtaking New Image

Something happened last month on a mountain in Chile that reminds us how endings birth the most beautiful beginnings.

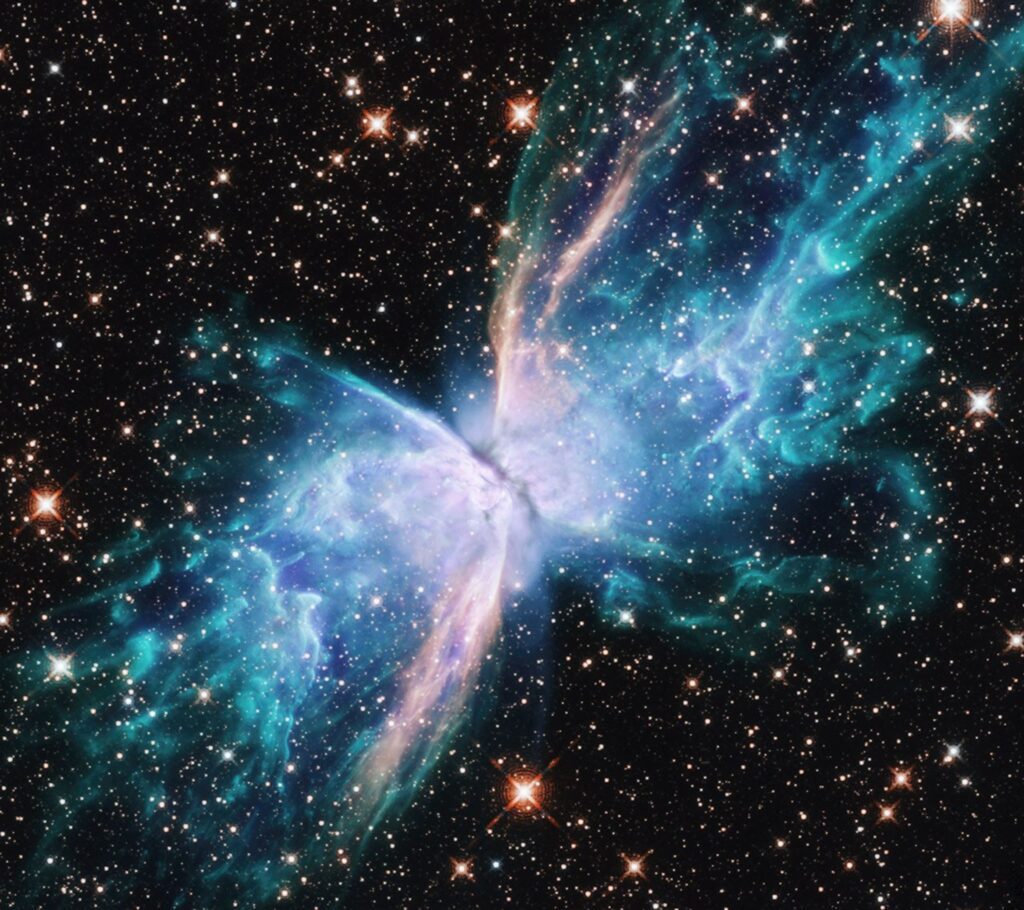

A telescope pointed toward Scorpius, hunting for proof that death can wear wings. What came back stopped astronomers in their tracks because nature had painted transformation across 3,800 light-years of space. Wings spread wide, colors bleeding red and blue, a creature frozen mid-flight between what was and what will be.

We call it a butterfly, but butterflies don’t burn at 250,000 degrees Celsius or stretch their wingspan across trillions of miles. Yet here floats something that mirrors every metamorphosis you’ve ever witnessed on Earth, only magnified to cosmic scale. Something that whispers a truth we forget too often when we fear our own endings.

Gemini South telescope captured what Chilean students chose to see, and their choice tells us something about how young minds understand what older eyes sometimes miss.

Wings Made of Star Dust Glow Across the Cosmos

NGC 6302 drifts between 2,500 and 3,800 light-years from where you sit reading these words, each light-year spanning six trillion miles of empty space. Scorpius holds this cosmic butterfly in its constellation, a jewel box of dying stars and newborn worlds, where endings and beginnings dance together without shame.

Gemini South sits atop Cerro Pachón, half of an international observatory that watches both hemispheres spin beneath the stars. Its 8.1-meter mirror collected photons that left NGC 6302 before human civilization built its first cities, before we learned to write our stories down, before we forgot how to read the stories written in light.

Glowing wings billow outward in the image released by NOIRLab on a Wednesday in November 2025, each wing painted in colors that speak of violence and beauty mixed together. Red traces where hydrogen burns hot under radiation’s whip while blue marks oxygen’s glow, both elements screaming their presence across the void. Between these wings, darkness forms a band like a waist cinched tight, holding back what wants to explode outward in all directions at once.

Students voted for this target, chose this butterfly over countless other cosmic wonders their telescope could chase. Maybe they saw in those wings something that resonated with their own transformations, their own shedding of childhood skins to become whatever comes next.

Death Births Beauty in Deep Space

At the heart of those butterfly wings hides a ghost star, a white dwarf smaller than Earth but dense enough to bend space around its corpse. What remains after a star strips itself naked weighs two-thirds as much as our Sun, compressed into a sphere that would fit between New York and Los Angeles.

More than 2,000 years ago, this white dwarf cast off the outer layers that once made it a giant among stars. Gas and dust that formed its body for billions of years got thrown into space like a coat too heavy for summer, and that discarded material now forms the wings we see glowing across the dark.

Heat from the dying star’s core pumps into those wings at temperatures exceeding 20,000 degrees Celsius, hot enough to make the abandoned gas shine like neon signs spelling out the star’s final message. Radiation streams from its surface where temperatures climb past 250,000 degrees Celsius, making this white dwarf one of the hottest stellar corpses we know.

Red hydrogen burns bright where the star’s wind slams into slower-moving gas, while blue oxygen marks the fastest zones where stellar winds reached three million kilometers per hour. Between these colors, sulfur and nitrogen add their signatures alongside iron and other elements, each one a building block for worlds yet to form.

Beauty often grows from what we thought was ending, from the parts we had to release to become what waited on the other side of transformation.

Chilean Students Choose Symbol of Transformation

Twenty-five years ago, Gemini South opened its eye for the first time and looked up at southern skies from its perch on Cerro Pachón. November 2000 marked that first light, when the telescope proved it could see what human eyes alone would miss, and a quarter-century later, students in Chile got to decide how to celebrate that milestone.

“This picturesque object was chosen as a target for the 8.1-meter telescope by students in Chile as part of the Gemini First Light Anniversary Image Contest,” NOIRLab explained when releasing the image to the world. Young minds engaged with astronomy through voting, through choice, through claiming ownership of the knowledge that telescopes in their country pull down from the heavens.

International Gemini Observatory operates two telescopes, one in Chile and one in Hawaii, both watching different halves of our sky. Chile’s students could have chosen anything their telescope could reach, any galaxy or nebula or dying star, but they picked the butterfly because sometimes we need to see transformation captured in light that traveled thousands of years to reach our eyes.

Gemini First Light Anniversary Image Contest connected students in host locations to the telescopes built on their land, letting them participate in science that often feels distant from daily life. When you’re young, everything feels like transformation because you’re still becoming whatever you’ll be, still shedding old skins and growing new ones, still learning that endings feed beginnings if you let them.

From Giant to Ghost Star

Before it became a white dwarf, before it stripped down to its dense core, this star bloated into a red giant whose diameter measured 1,000 times wider than our Sun. Imagine a sphere so vast that Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars could orbit inside its surface, swimming through stellar atmosphere like fish in an ocean of fire.

Red giants happen when stars burn through their hydrogen fuel and start fusing helium in their cores, causing outer layers to expand like a balloon filling with hot air. Our own Sun will become a red giant in about five billion years, swelling until Earth’s orbit runs through solar atmosphere, baking our planet to cinders.

NGC 6302’s parent star began shedding its outer layers while still a red giant, expelling gas from its equator in a slow, steady wind that formed a dark doughnut-shaped band still visible around the central white dwarf. Other gas got pushed out perpendicular to this equatorial band, restricted by the material already floating in the plane of the star’s rotation.

Bipolar structure emerged from these competing flows, with gas able to escape more freely above and below the equatorial disk than through it. Wings took shape where gas found the path of least resistance, where stellar wind could blow unobstructed into empty space, where transformation followed the rules physics wrote billions of years before life crawled onto land.

Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 identified the central star as a white dwarf in 2009, measuring its mass and temperature and confirming what astronomers suspected about how large the original star must have been. Only massive stars create white dwarfs this hot, this small, this dense. Only giants become ghosts that burn bright enough to light up the gas they left behind.

Stellar Winds Sculpt Cosmic Wings

After the red giant phase ended, after the star collapsed into its white dwarf form, something dramatic happened that shaped the butterfly wings we see today. Powerful stellar wind exploded from the dying star’s surface, tearing through the wings at speeds exceeding three million kilometers per hour, fast enough to cross the distance between Earth and the Moon in less than eight minutes.

Fast-moving gas slammed into slower material expelled earlier, creating shock waves that sculpted cloudy ridges and towering pillars throughout the nebula. Textures emerged from violence, beauty born from collision, as if nature needed these opposing forces to paint details into what might have been a simple sphere of glowing gas.

Ridges rise like mountain ranges made of ionized hydrogen, casting shadows across regions where oxygen burns blue. Pillars stretch outward like fingers reaching for something just beyond grasp, each one marking where dense knots of gas resisted the stellar wind’s push. Between these structures, cavities open like windows punched through fabric, showing deeper layers of the nebula behind the brightest surfaces.

Interactions between wind speeds continue shaping NGC 6302 even now, even as we watch from Earth with telescopes built on mountains in Chile. Gas expands outward at different rates, creating eddies and swirls that won’t settle for thousands of years, if ever. Change happens on timescales that make human lifetimes look like heartbeats, yet the same forces that sculpted these wings sculpt our lives if we pay attention.

Discovery Mystery Spans Two Centuries

Nobody knows exactly when human eyes first spotted NGC 6302 through a telescope, though credit often goes to American astronomer Edward E. Barnard for his 1907 study of the object. Barnard cataloged many nebulae and dark clouds during his career, mapping the sky with patience that modern astronomers using digital cameras can barely imagine.

Scottish astronomer James Dunlop may have discovered NGC 6302 much earlier, possibly as far back as 1826 when he surveyed southern skies from Australia. Records from that era remain incomplete, and many observers recorded objects without realizing someone else had already found them. Telescopes improved slowly, and communication between observatories moved at the speed of ships crossing oceans rather than emails crossing continents in seconds.

Multiple names attach to NGC 6302 because different catalogs assigned different designations over the decades. Bug Nebula describes its insect-like shape, while Caldwell 69 refers to its number in Patrick Moore’s Caldwell Catalogue of astronomical objects. Butterfly Nebula captures what most people see when they look at images of this object, though bugs and butterflies share similar body plans when viewed from above.

Official designation NGC 6302 comes from the New General Catalogue, compiled by John Louis Emil Dreyer in 1888. Numbers in that catalog still serve as primary identifiers for thousands of deep-sky objects, even though we’ve learned so much more about what these objects actually are since Dreyer published his work.

Seeds for New Worlds Float in Nebula Gas

Everything you see in those glowing wings will eventually become something else because the universe wastes nothing. Hydrogen expelled by the dying star will drift through space until gravity pulls it into new clouds, new stars, new chances at planetary systems where life might emerge.

Oxygen atoms glowing blue in the butterfly wings will someday form water molecules on worlds orbiting stars not yet born. Iron scattered through the nebula will condense into planetary cores and mountain ranges and the hemoglobin in blood cells carrying oxygen through alien veins. Nitrogen will build amino acids, sulfur will enable protein chemistry, carbon will form the backbone of whatever life follows us.

NOIRLab Legacy Imaging Program captures these moments of transition, these snapshots of death becoming life, using observing time on telescopes specifically dedicated to acquiring data for color images shared with the public. What started as the Gemini Legacy Imaging Program in 2002 now continues across multiple telescopes, turning science into art that anyone can appreciate.

Elements found in NGC 6302 represent the periodic table entries necessary for complexity, for chemistry beyond simple hydrogen fusion, for planets with solid surfaces and liquid oceans and atmospheres that can hold life. Without stars dying and releasing these heavier elements into space, the universe would remain a soup of hydrogen and helium, unable to build anything interesting.

Every atom in your body came from stars that died before our Sun formed, which means you are made of stellar ghosts wearing new shapes, transformation completed at atomic scale. What you think of as yourself is really ancient stardust that learned to ask questions about where it came from and where it’s going next.

Embrace Your Own Metamorphosis

Butterfly nebulae teach us what caterpillars already know when they dissolve inside their chrysalis. Sometimes you have to fall apart completely before you can become what you were meant to be, and there’s no way around that dissolution, only through it.

NGC 6302 burned for billions of years as a stable star, fusing hydrogen in its core, holding itself together against gravity’s crushing embrace. When fuel ran low, stability became impossible and the star had to choose between collapse and expansion. It chose both, collapsing its core while expanding its outer layers, becoming two things at once before finally settling into the ghost form it wears now.

We face similar choices when life demands transformation from us. We can resist, trying to maintain forms that no longer serve us, or we can release what needs releasing and trust that something beautiful waits on the other side. Stars don’t resist their evolution because they understand that fighting physics only delays what must happen eventually.

Wings made of discarded material glow brighter than the star that cast them off ever did during its stable phase. Sometimes what we release becomes more luminous than what we were holding onto, more visible to others, more capable of inspiring those who see it from far away.

Chilean students who voted to image NGC 6302 saw something worth celebrating in a dying star’s final act of creation. Maybe they recognized that schools and telescopes and education itself exist to help us transform, to shed ignorance like a snake sheds skin, to become versions of ourselves that can see farther and understand deeper than we could before.

Your own metamorphosis waits for you to stop fighting it and start feeding it instead. Whatever needs to die in your life so something new can live deserves the same grace we give to stars burning themselves out across the cosmos. Let it go, watch it glow, and trust that the wings you’re growing will carry you places your current form never could reach. Beauty births itself from endings brave enough to become beginnings.

Loading...