Bernie Sanders Calls for a Shorter Workweek in an Age of Artificial Intelligence

We live in a time where machines are learning faster than humans are resting. Every notification promises efficiency, every upgrade claims to save time, yet somehow time feels more scarce than ever. We tell ourselves this is progress, but rarely stop to ask a quieter question. If technology is doing more of the work, why do so many people feel more tired, more anxious, and more pressed for time than previous generations.

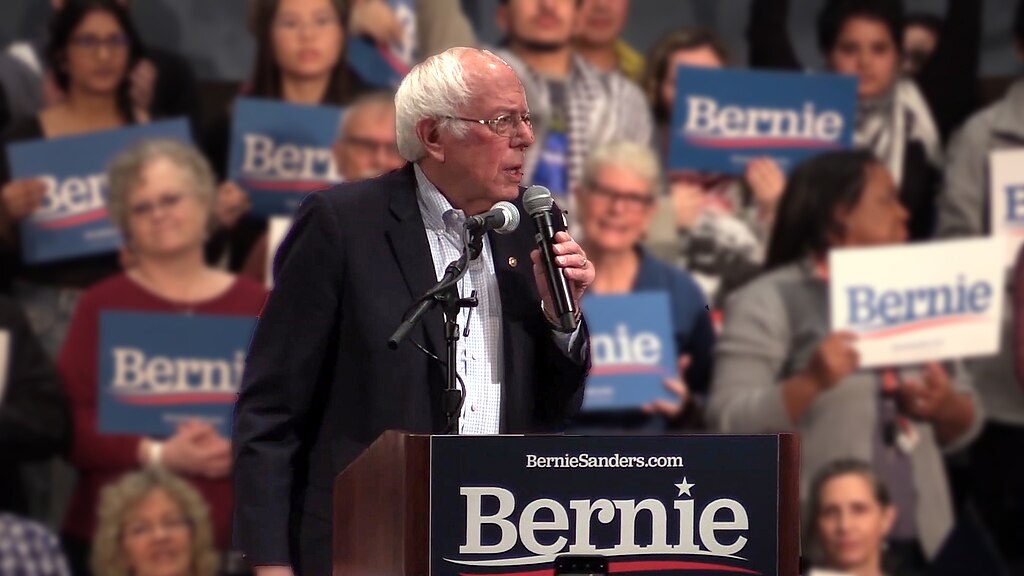

This is where Senator Bernie Sanders has stepped into the conversation, not by talking about gadgets or algorithms, but by questioning a belief many of us have accepted without debate. The idea that a meaningful working life must consume the majority of our waking hours. In recent public discussions, he has suggested that artificial intelligence should not push people closer to the edge of exhaustion, but instead open the door to something unfamiliar in modern culture. More time to live.

That question lands at a moment when burnout has become almost normalized and mental strain is treated as a personal failure rather than a structural issue. Across wellness, psychology, and spiritual traditions, there is growing agreement that tying human value too tightly to output carries a cost. Sanders speaks in the language of policy and labor, but underneath it is a deeper challenge. To reconsider what progress is meant to serve, and whether a future shaped by intelligent machines can also be one that honors human wellbeing.

When Progress Stopped Giving Time Back

There was a period in American history when working harder actually led to living better. As productivity rose, wages followed, and families felt the difference in their daily lives. That relationship slowly fractured. Over time, output continued to climb while hours stayed long and financial security became harder to reach. Many people today are producing more than ever, yet feeling increasingly stretched, uncertain, and worn down by work that never seems to end.

Artificial intelligence has intensified this disconnect. Software now assists with writing, scheduling, logistics, customer service, and even medical analysis, reshaping how work gets done across industries. Government data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that productivity has continued to rise, but surveys consistently reveal growing exhaustion and anxiety among workers. The promise of efficiency has not translated into relief. Instead, it has often raised expectations while shrinking the margin for rest.

Senator Bernie Sanders argues that this outcome is not an accident of technology but a result of political and economic choices. Speaking on the Joe Rogan Experience, he framed the issue plainly: “You’re a worker, your productivity is increasing because we give you AI, right? Instead of throwing you out on the street, I’m going to reduce your workweek to 32 hours.” His point echoes a growing body of scientific research. Studies published in Occupational Health Science and related journals have found that extended work hours are linked to higher rates of depression, disrupted sleep, and cardiovascular strain. When productivity gains are not paired with reduced workload, stress increases rather than fades. Sanders is asking a deeper question. If technology is making work more efficient, why are human beings paying the cost with their health.

Rewriting the Rules of a Workweek

Bernie Sanders did not present his idea as a slogan or a thought experiment. He put it into legislation. In 2023, he introduced the Thirty Two Hour Workweek Act, a proposal rooted in a simple shift rather than a radical ban. The bill does not prevent people from working longer weeks. Instead, it changes how that time is valued. Under the proposal, any work beyond thirty two hours would qualify for overtime pay, signaling that extra labor should come with real compensation rather than being treated as a default expectation.

The structure of the plan reflects an awareness of economic reality. Rather than forcing an immediate transition, the proposal outlines a gradual four year rollout that allows businesses time to adapt their staffing, workflows, and internal culture. Sanders has pointed out that similar reductions in working hours throughout US history were initially met with concern and resistance, only to later become accepted standards. What once felt disruptive eventually became normal.

Evidence from outside the United States adds weight to the argument. Large scale trials of four day workweeks in countries such as Iceland and the United Kingdom have shown that reducing hours does not necessarily reduce output. In the UK, a pilot program coordinated by researchers at the University of Cambridge found that most participating companies chose to continue with shorter workweeks after the trial ended, citing stable or improved productivity along with better employee wellbeing. These results challenge the belief that longer hours automatically lead to better performance. From a wellness perspective, they reinforce a principle supported by both science and lived experience. Rest is not a reward for productivity. It is one of its foundations.

Time as a Democratic Issue

When conversations about work focus only on efficiency or profit, something essential gets left out. Time is not just a personal resource. It is a civic one. The amount of time people have outside of work shapes how they participate in family life, community life, and democracy itself. When schedules are packed and exhaustion is constant, engagement shrinks. People stop attending town halls, volunteering, organizing, or even staying informed. Democracy quietly weakens when citizens are too tired to take part.

Bernie Sanders has connected this reality to the rise of artificial intelligence in a way that goes beyond economics. As technology increases productivity, he has argued that society faces a choice. Either allow those gains to further concentrate power and decision making among a small group, or translate them into time that allows ordinary people to show up more fully in public life. Time to think critically. Time to engage. Time to participate rather than simply endure.

Research in political science and public health supports this connection. Studies have shown that long working hours are associated with lower civic participation and reduced trust in institutions. When survival takes up most of a person’s energy, long term thinking becomes a luxury. A shorter workweek does not guarantee a healthier democracy, but it creates the conditions for one. It gives people the breathing room required to reconnect with each other and with the systems that govern their lives.

This is where the conversation about AI quietly becomes a conversation about values. Technology can compress time or it can return it. If progress only accelerates output while shrinking human presence in civic spaces, something vital is lost. The question Sanders raises is not only how we work, but what kind of society we are trying to sustain with the time that technology gives back.

When Technology Redefines Human Worth

One of the quiet risks of artificial intelligence is not job loss alone, but the way it can subtly reshape how people measure their value. In cultures where identity is tightly bound to occupation, efficiency becomes a proxy for worth. As machines grow faster and more capable, this comparison becomes harder to escape. When an algorithm can outperform a human in speed or output, the unspoken question follows. What am I worth if I am no longer the most efficient option.

This concern sits beneath Bernie Sanders’ warnings about automation and inequality. His focus is often economic, but the psychological implications are just as significant. When productivity becomes the primary lens through which society evaluates contribution, those displaced or pressured by technology are at risk of being seen as expendable rather than supported. This framing can deepen shame, anxiety, and social fragmentation, especially in communities already facing economic stress.

Mental health research has long shown that unemployment and job insecurity are linked to higher rates of depression, substance use, and chronic stress. These effects are not simply about income. They are about meaning and belonging. A system that rewards output without safeguarding dignity leaves many people feeling invisible. Reducing work hours without addressing this deeper issue would be incomplete.

A shorter workweek reframes the conversation. It suggests that value does not come only from hours logged or tasks completed. It comes from being human in a society that recognizes limits. In an era shaped by intelligent machines, preserving human worth may depend less on competing with technology and more on designing systems that protect identity, dignity, and mental health alongside economic stability.

Choosing What Progress Is For

Artificial intelligence will continue to advance, whether society feels ready or not. The deeper question is not how powerful these tools will become, but how deliberately their benefits are distributed. A future where productivity rises while exhaustion deepens is not a technological failure. It is a values failure. Bernie Sanders’ call for a shorter workweek asks us to confront what progress is meant to serve and whether economic systems are designed around human wellbeing or human output.

This moment offers a choice. Technology can either compress life into tighter schedules and higher expectations, or it can return something many people have quietly lost. Time to rest. Time to connect. Time to participate in family, community, and democracy. The conversation about a thirty two hour workweek is ultimately a conversation about dignity. If progress does not leave people healthier, more present, and more whole, then it is worth asking what kind of progress it really is.

Featured Image from Shelly Prevost from San Francisco, United States, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Loading...