Why Greenland’s Hidden Geology Has the Whole World Watching

Somewhere between Iceland and Canada lies an island holding secrets billions of years old. Most people picture endless white when they think of Greenland. They imagine polar bears, glaciers, and frozen silence. What they rarely consider is what lies beneath all that ice.

Earth’s largest island has become the subject of intense global interest. Politicians debate its future. Mining companies eye its potential. Scientists probe its depths with radar and drills. And yet, for all the attention, Greenland remains one of the least understood places on the planet.

Something about Greenland makes it different from anywhere else. Something in its rocks tells a story of fire, pressure, and time that stretches back almost four billion years. What that story reveals could change how we power our world, build our technology, and fight climate change. But first, we need to understand what makes Greenland so special in the first place.

A History Written in Stone

Near a place called Isua in West Greenland, rocks jut from the earth that formed when our planet was still young. At 3.8 billion years old, they rank among the oldest materials on Earth’s surface. Walking here feels like stepping through a geological time machine.

Greenland’s story spans almost the entire history of our planet. Mountain ranges rose and fell. Continents collided and split apart. Volcanoes erupted and went quiet. Each event left its mark on the stone.

Jonathan Paul, an Associate Professor in Earth Science at Royal Holloway, University of London, puts it plainly. “Geologically speaking, it is highly unusual (and exciting for geologists like me) for one area to have experienced all three key ways that natural resources – from oil and gas to REEs and gems – are generated.”

Those three processes include mountain building, rifting, and volcanic activity. Mountain-building events cracked Greenland’s crust over billions of years. Gold, rubies, and graphite settled into those faults and fractures. Rifting periods stretched the land apart, eventually opening the Atlantic Ocean just over 200 million years ago. Volcanic activity deposited rare metals in igneous rock layers, similar to what happened in Iceland.

Most places on Earth experienced one or two of these processes. Greenland experienced all three. That geological jackpot explains why the island holds such diverse mineral wealth.

Hidden Beneath the White

Ice covers 80% of Greenland. Measuring up to three kilometers thick in some places, it forms the second-largest ice body on Earth after Antarctica. Only about 410,000 square kilometers remain ice-free, an area roughly the size of Norway.

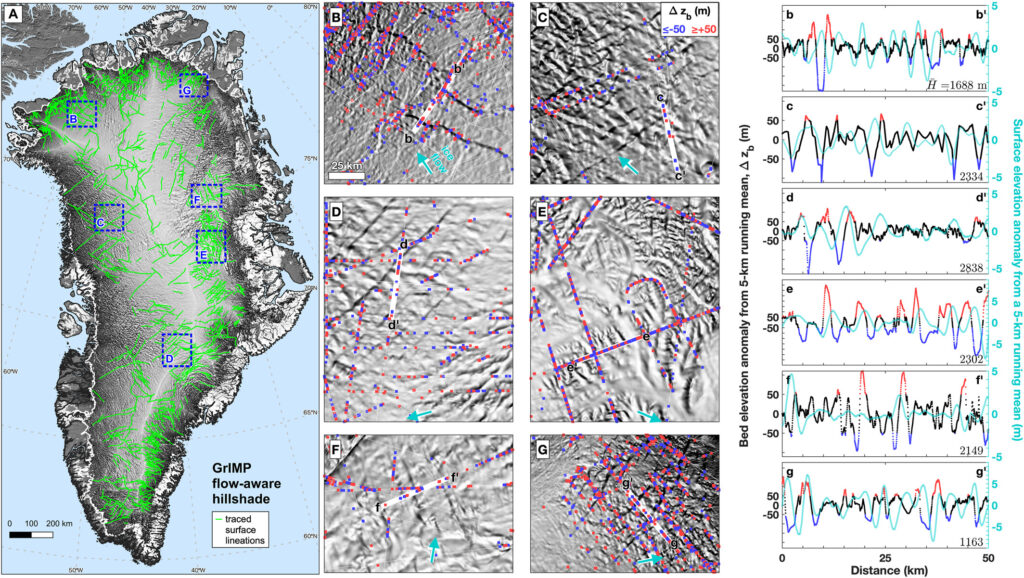

What lies beneath all that frozen water has long remained a mystery. But new technology is changing that. Scientists now use ground-penetrating radar to map bedrock below up to two kilometers of ice. What they have found hints at vast, untapped resources buried in the island’s frozen interior.

Consider rare earth elements. Greenland holds three REE-bearing deposits that may rank among the world’s largest by volume. Reserves of dysprosium and neodymium alone could satisfy more than a quarter of predicted future global demand, totaling nearly 40 million tonnes combined. Wind turbines need these materials. Electric vehicle motors require them. Nuclear reactor magnets cannot function without them.

Oil and gas deposits add another layer to Greenland’s wealth. US Geological Survey estimates suggest northeast Greenland holds around 31 billion barrels of oil-equivalent in hydrocarbons. For comparison, that matches the entire volume of proven crude oil reserves in the United States.

Sedimentary basins contain lead, copper, iron, and zinc. Local mining of these metals dates back to 1780. Diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes were discovered in the 1970s but remain unexploited due to logistical challenges. Even truck-sized lumps of native iron exist here, formed not from meteorites but from Earth itself.

From Cryolite to Rubies

Mining in Greenland has a longer history than most people realize. Modern mineral exploration began in the early 18th century, though operations remained small for centuries.

Ivigtut Cryolite Mine stands as the most successful example. Operating for over 130 years from 1854 to 1987, it extracted a mineral critical for aluminum processing. At its peak, the mine was the only source of natural cryolite in the world.

Black Angel lead-zinc mine at Maarmorilik ran from 1973 to 1990, producing 11.2 million tonnes of ore. Miners reached the deposit via cable car, traveling 600 meters above sea level to an adit carved into a precipitous cliff face.

Nalunaq Gold Mine operated from 2004 to 2013 in South Greenland, producing over 11 tonnes of gold from a high-grade quartz vein. Plans exist to reopen the mine in the coming years.

Today, two mines operate on the island. Greenland Ruby at Aappaluttoq produces rubies and pink sapphires. White Mountain mine near Kangerlussuaq extracts anorthosite for fiberglass production. Neither has yet achieved profitability, but both represent important steps toward a more active mining sector.

Infrastructure in a Land Without Roads

Operating in Greenland presents challenges found almost nowhere else. No roads connect any of the island’s 17 towns and 60 settlements. Helicopters, boats, and planes provide the only transportation between communities.

Harsh Arctic climate and rugged terrain drive up costs for everything. Companies must build their own energy supply, water systems, and communication lines. Fresh supplies arrive by sea or air, often with long delays during the winter months.

Deep fjords offer one advantage. Often several hundred meters deep, they provide natural harbors for large bulk carrier ships. Hydroelectric power supplies over 70% of electricity and heat in the towns it reaches, offering clean energy for potential mining operations.

Still, remoteness remains the defining challenge. When equipment breaks at a mine site, replacement parts might take weeks to arrive. Labor shortages plague the construction industry, making it difficult for mining companies to find workers. Many skilled Greenlanders already work on government infrastructure projects that pay competitive wages.

A Paradox of Ice and Fire

Climate change has begun reshaping Greenland in ways both alarming and ironic. An area the size of Albania has melted since 1995. Scientists project continued shrinkage of the ice cap in the coming decades.

As ice retreats, it exposes resources needed for clean energy technology. Solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles all require rare earth elements and other materials that Greenland holds in abundance. Mining those resources could accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels.

But extraction comes with costs. Mining operations would add to carbon emissions. Development could damage pristine landscapes. Rising sea levels already threaten to swamp the coastal settlements where most Greenlanders live.

Paul frames the tension as a question for Greenland to answer. “Should Greenland’s increasingly available resource wealth be extracted with gusto, in order to sustain and enhance the energy transition?” He notes that doing so would add to climate change effects on Greenland and beyond, including despoiling pristine landscapes and contributing to sea level rise.

No easy answer exists. Greenland needs economic development to reduce its dependence on fishing and Danish subsidies. Mining offers one path forward. But at what environmental cost?

Politics and Power

Greenland gained self-government in 2009, taking full authority over mineral resources from January 2010. A parliament of 31 members sets policy from the capital Nuuk. Denmark retains control over foreign affairs and defense, but Greenlanders increasingly chart their own course.

International interest in the island has surged. During summer 2019, US President Donald Trump stated he was interested in buying Greenland. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen called the idea absurd. Greenland’s government offered a pointed response, declaring the island “open for business, not for sale.”

American interest has not faded. A US consulate opened in Nuuk. Millions of dollars flow toward consulting projects in tourism, mining, and education. China has also shown interest, with a Hong Kong-based company acquiring rights to an iron ore project.

Legal frameworks dating from the 1970s regulate all mining and resource extraction. Impact Benefit Agreements require companies to employ local Greenland labor and engage with affected communities. Environmental assessments must pass public consultation before projects can proceed.

Pressure to loosen these controls may increase as global demand for critical minerals grows. Greenland must balance economic opportunity against environmental protection and cultural preservation.

Greenland at the Crossroads

Greenland sits at a crossroads. Beneath its ice lie materials the world needs for a clean energy future. Its rocks hold secrets about Earth’s earliest history. Its people seek prosperity while protecting their home.

Mining exploration peaked in 2011 with investments approaching 700 million Danish kroner. Activity slowed during a global mining downturn but has begun recovering. New mineral strategies aim to attract investment while maintaining environmental standards.

Several projects inch toward production. A major rare earth development at Kvanefjeld in South Greenland could shift global markets for these critical materials. Lead-zinc deposits at Citronen Fjord in the far north await further financing. The Nalunaq gold mine may reopen.

Whether these projects succeed depends on many factors. Commodity prices fluctuate. Infrastructure costs remain high. Climate change introduces new uncertainties. Political winds shift.

What remains constant is the geology. Four billion years of Earth’s history created something remarkable beneath Greenland’s ice and stone. Understanding that history helps us appreciate what makes this frozen island so extraordinary. The treasure is real. The question is what we choose to do with it.

Loading...