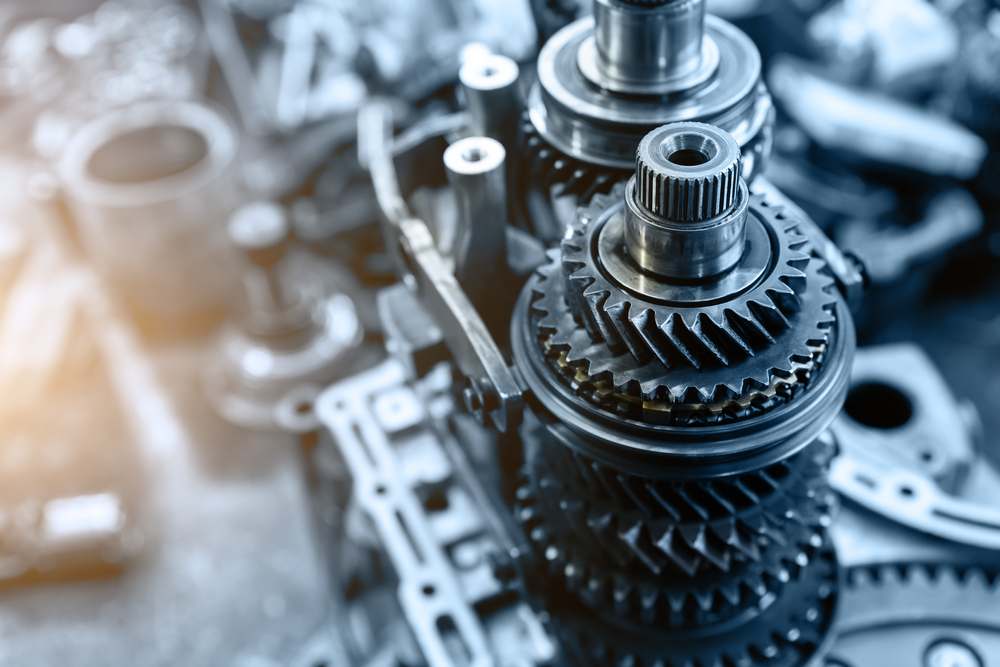

Gears Were One of Humanity’s First Technologies. What Happens When We Rethink Them?

For thousands of years, gears have quietly carried civilization forward.

They’ve turned the wheels of chariots, tracked the movement of planets, powered clocks, factories, and robots. They are so familiar, so fundamental, that most of us never stop to ask a deeper question: what assumptions are hidden inside the technologies we’ve inherited?

Today, a group of scientists is asking that exact question not by rejecting the past, but by listening to it carefully. Their work suggests that even the most ancient inventions still have room to evolve, and that progress doesn’t always come from adding more complexity, but sometimes from letting go.

The Ancient Intelligence Embedded in Gears

Around the third century BCE, Chinese engineers created what is widely considered the first differential gear system. It powered a remarkable device known as the south pointing chariota wheeled vehicle whose pointer always indicated south, no matter how the chariot turned. Long before GPS or compasses became widespread, this machine embodied a deep understanding of motion, balance, and feedback.

Centuries later, engineers in ancient Greece built the Antikythera Mechanism, an intricate assembly of interlocking gears designed to predict astronomical events. Often described as the world’s first analog computer, it remains so complex that scientists are still decoding how it worked.

These inventions remind us of something easy to forget: our ancestors were not primitive thinkers. They were precise observers of nature who learned to translate motion into meaning.

Yet even these masterpieces carried an inherent weakness.

The Hidden Fragility of Perfect Alignment

Traditional gears rely on sustained solid contact. For motion to transfer efficiently, their teeth must remain precisely aligned, not just at the moment of manufacture but throughout a machine’s entire operating life. That requirement ties performance to physical conditions that are constantly changing. Heat causes materials to expand. Repeated loads introduce microscopic deformation. Lubricants thin, migrate, or degrade. Each change slightly alters alignment, and over time those small shifts accumulate into vibration, noise, energy loss, and eventual failure.

This sensitivity places strict constraints on engineering design. Systems that depend on tight alignment demand narrow manufacturing tolerances, continual calibration, and routine maintenance to remain functional. In complex machines, misalignment in one component can propagate through connected parts, reducing efficiency well before any obvious damage appears. Mechanical engineering research consistently identifies contact driven transmission as a major contributor to long term wear in rotating systems, especially in environments with dust, moisture, or temperature variation.

To manage this fragility, engineers have historically added layers of protection and redundancy. Housings, lubrication systems, and precision assemblies improve reliability but also increase cost, weight, and complexity. These tradeoffs become even more restrictive at smaller scales, where minor surface imperfections can overwhelm performance. In this sense, the limitation is not a failure of design skill but a boundary imposed by physics itself. Any mechanism that depends on continuous contact must contend with friction, wear, and misalignment.

That reality reframes the problem. Instead of asking how to preserve perfect alignment indefinitely, engineers began to ask a different question. What if gears did not have to touch at all?

Replacing Teeth With Flow

In a study published in Physical Review Letters, researchers at New York University explored a radically different idea. Instead of interlocking metal teeth, they asked whether carefully controlled fluid motion could transfer rotation between objects.

“We invented new types of gears that engage by spinning up fluid rather than interlocking teeth,” said Jun Zhang, the study’s senior author, in a press statement. “And we discovered new capabilities for controlling the rotation speed and even direction.”

The teamled by Zhang alongside Leif Ristroph and doctoral researcher Jesse Etan Smithimmersed two cylindrical rotors in a glycerol water mixture. One rotor was actively driven by a motor. The other was passive, free to respond only to the surrounding flow.

To make the invisible visible, the researchers added tiny air bubbles to the liquid, allowing them to track how motion traveled through the fluid.

What they found challenged centuries of mechanical intuition.

When Gears Behave Like Belts

At close distances and lower speeds, the system behaved much like traditional gears. Fluid trapped between the rotors acted like invisible teeth, causing the passive rotor to spin in the opposite direction of the active one.

But when the distance increasedor when the driving speed changedthe behavior flipped.

Instead of being confined between the rotors, the fluid wrapped around the outside of the passive cylinder. In this configuration, the passive rotor began spinning in the same direction as the driven one, similar to how a belt connects two pulleys.

“Regular gears have to be carefully designed so their teeth mesh just right, and any defect, incorrect spacing, or bit of grit causes them to jam,” Ristroph explained. “Fluid gears are free of all these problems, and the speed and even direction can be changed in ways not possible with mechanical gears.”

What mattered most was not the history of the system, but its present conditions. Change the spacing or speed, and the direction of rotation could reversereliably and predictably.

The Physics Beneath the Motion

A closer analysis revealed why these reversals occur. Fluid sliding along the inner side of the passive rotor tends to push it one way, while fluid sweeping around the outer side pushes it the opposite way. The rotor’s motion depends on which influence dominates.

“At very small gaps, the inner shear region shrinks, letting outer flow dominate and causing same direction rotation,” Zhang explained in an interview. “At intermediate gaps, inner shear regains control, restoring counterrotation. At larger distances, the overall flow pattern reorganizes again, flipping the outcome once more.”

Speed plays a crucial role as well. Faster rotation increases inertial effects in the fluid, causing flows to spiral outward instead of looping tightly. When that balance tips, direction changes.

This may sound abstract, but it reflects a broader truth: systems don’t just respond to forcethey respond to context.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

The significance of this research lies less in the specific experiment and more in the design possibilities it opens. By demonstrating that rotational motion can be transmitted without solid contact, the work points to mechanical systems that are inherently more tolerant of uncertainty. In real world conditions, machines rarely operate in clean, stable environments. Variations in temperature, contamination, and loading are the norm rather than the exception. A transmission method that remains functional under these conditions addresses a long standing gap between idealized design and practical use.

This matters especially in contexts where maintenance is difficult, costly, or impossible. Systems used in sealed devices, remote infrastructure, or hazardous environments often fail not because they are poorly designed, but because they rely on components that degrade predictably with contact. Removing direct contact changes the failure profile entirely. Instead of gradual wear at points of friction, performance becomes a function of controllable parameters such as geometry, spacing, and speed.

The implications extend to scale as well. As devices shrink, traditional mechanical components become increasingly sensitive to surface imperfections and alignment errors. At small scales, even minor defects can dominate behavior. Fluid mediated motion offers an alternative that scales more gracefully, which is why the findings are relevant to micro scale engineering and to emerging technologies that require precise control without rigid constraints.

Beyond engineering applications, the study also contributes to a clearer understanding of how rotating objects influence one another through surrounding media. This insight informs models used in fields ranging from energy systems to biology, where interaction through fluid flow plays a central role. By isolating rotation as the primary variable, the research provides a framework that can be applied well beyond the specific system tested in the lab.

A Deeper Lesson in Progress

There is something quietly profound about this discovery, not because it overturns history, but because of how it reframes it. For nearly five thousand years, we accepted that gears must have teeth. We refined their shapes, strengthened their materials, and built entire systems around that belief. Progress meant optimization. Then someone paused and asked a more fundamental question. What if the teeth were not essential at all.

That shift, from improving an assumption to questioning it, is where real transformation begins. It marks the difference between reinforcing a structure and re examining its foundation. In engineering, this moment opened space for systems that respond differently to stress and uncertainty. In life, the same pattern repeats.

Many of the systems we navigate daily, our work culture, our relationships, our definitions of success, rest on inherited assumptions. When they strain, we compensate. We add safeguards. We normalize maintenance. Rarely do we ask whether the underlying design still serves who we are now.

The scientists behind fluid based gears did not reject the past. They studied it, respected its intelligence, and then allowed themselves to move differently. And perhaps that is the invitation here. To notice which long held ideas in our own lives are ready to evolve, not through force, but through a willingness to let new patterns take shape.

Featured Image from Shutterstock

Loading...