Scientists Discovered How to Kill a Brain Cancer That Has No Known Cure

Imagine hearing a doctor tell you that you have roughly 15 months to live. No second opinion will change the number. No experimental drug will buy you more than a handful of weeks. Your brain, the organ that stores every memory you have ever made, every word you have ever learned, every face you have ever loved, is being consumed from the inside out by something no surgeon can fully remove and no medication can stop.

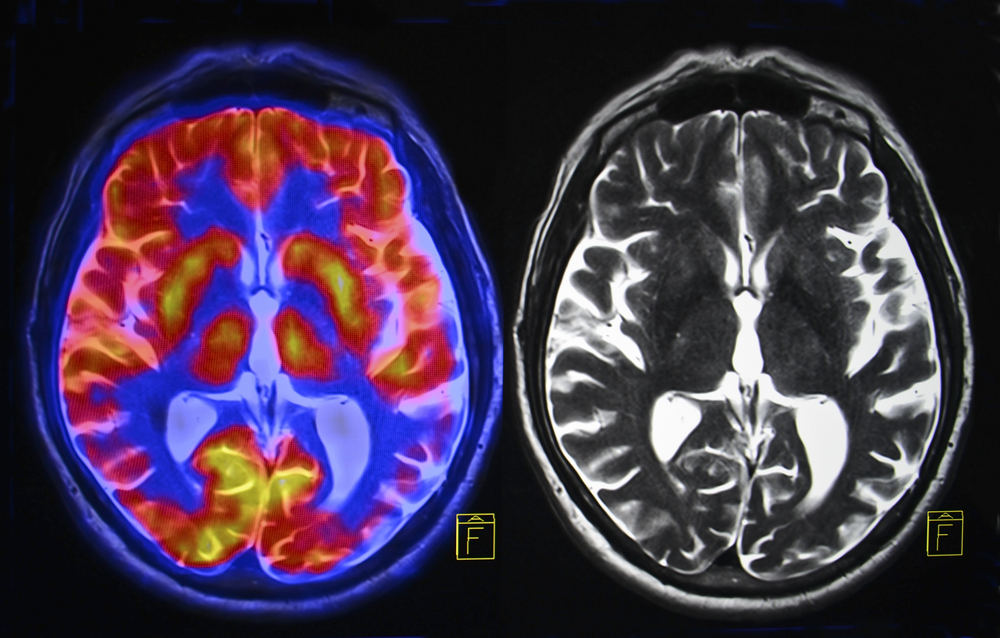

For the more than 14,000 Americans diagnosed with glioblastoma every year, that nightmare becomes reality. Glioblastoma is the most common primary brain cancer in adults, and it is almost always fatal. Only one in 20 patients will still be alive five years after diagnosis. Most will not see two years.

Surgery can remove some of it, but glioblastoma does not grow like a neat, contained lump. It threads itself through brain tissue like roots spreading through soil, making complete removal nearly impossible. Chemotherapy and radiation can follow surgery, but they add mere months rather than years. And those months often come at a steep cost to quality of life, leaving some patients to make the agonizing decision to forgo treatment altogether.

But somewhere in a lab at the University of Virginia, a researcher named Hui Li and his team have been quietly chasing something that could change all of this. And their latest findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggest they may have found it.

Decades of Failure Left Patients with Almost No Options

Before understanding what Li’s team discovered, it helps to understand just how bleak the situation has been for glioblastoma patients.

Standard treatment has barely evolved in decades. When radiation combined with the chemotherapy drug temozolomide showed it could extend survival by just 2.5 months, the medical community hailed it as a great success. Let that sink in. A 2.5-month improvement was considered a win because nothing else even came close.

Part of the problem is the brain itself. It protects itself behind something called the blood-brain barrier, a biological shield that keeps toxins and infections from reaching brain tissue. While that barrier does essential work, it also blocks many drugs from getting where they need to go. Researchers could develop promising compounds in the lab, only to watch them fail because they simply could not reach the tumor.

And even when treatments did reach the cancer, glioblastoma proved ruthless in its ability to resist them. Without a clear genetic target to aim for, doctors were fighting with blunt instruments against one of the most aggressive cancers known to medicine. “Glioblastoma is a devastating disease. Essentially no effective therapy exists,” Li said.

For years, that sentence could have served as both a diagnosis and a verdict. But Li refused to accept it as the final word.

A Childhood Cancer Accidentally Opened a Door

Sometimes the biggest breakthroughs arrive by accident. Li and his team were not even studying glioblastoma when they first stumbled onto the trail that would lead them here.

Instead, they were working on rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer that strikes children. Pediatric cancers tend to involve fewer genetic mutations than adult cancers, which makes them somewhat easier to decode. Researchers can study their mechanics without drowning in the noise of hundreds of competing mutations.

During that work, Li’s team noticed something unusual about a gene called AVIL. Something was off. Something worth investigating further.

AVIL, in its normal state, helps cells maintain their size and shape. It produces a protein that binds to actin, one of the key structural components inside cells. Under ordinary circumstances, it performs a quiet, unglamorous job. But what Li’s team saw in their pediatric cancer research hinted that AVIL might be capable of far more dangerous behavior under the right conditions.

Curious whether AVIL might be causing trouble beyond childhood cancers, the team turned its attention to adult cancers. And when they looked at glioblastoma, what they found was staggering.

In 2020, They Found Glioblastoma’s Hidden Engine

Li’s team published their findings in Nature Communications, and the results painted a striking picture. AVIL was overexpressed in 100% of the glioblastoma cells and clinical samples they examined. Even more telling, it appeared at higher levels in glioblastoma stem cells, which are believed to drive tumor regrowth after treatment.

Meanwhile, healthy brain tissue barely expressed AVIL at all. Here was a gene running at full speed in every glioblastoma sample tested, yet sitting almost silent in normal cells. For researchers hunting a treatment target, that kind of contrast is exactly what you hope to find.

Various factors can push AVIL into overdrive, and once that happens, it triggers cancer cells to form and multiply. When Li’s team blocked AVIL activity in lab mice, glioblastoma cells were destroyed. Healthy cells were left untouched. Knocking AVIL out entirely in mice produced no harmful effects, suggesting a wide window for potential treatment.

“The novel oncogene we discovered promises to be an Achilles’ heel of glioblastoma,” Li said at the time, “with its specific targeting potentially an effective approach for the treatment of the disease.”

But a significant gap remained between what worked in the lab and what could help a patient sitting in a hospital room. Silencing AVIL through genetic techniques proved the concept, but those techniques could not be safely used in humans. Li needed a different weapon, a molecule small enough to do the job inside a living person.

Screening Thousands of Compounds Led to One Powerful Molecule

Finding the right molecule meant testing an enormous number of candidates. Li’s team used a process called high-throughput screening, a method that rapidly evaluates massive libraries of chemical compounds to identify which ones interact with a specific target.

After sifting through thousands of possibilities, one small molecule rose above the rest. It bound directly to the AVIL protein and blocked AVIL from attaching to actin, effectively cutting off the gene’s ability to wreak havoc. When researchers compared the molecule’s effect on cells to what happened when AVIL was silenced through genetic methods, the results looked remarkably similar. It also reduced levels of FOXM1 and LIN28B, two proteins known to operate downstream of AVIL in the cancer pathway.

Most important for practical purposes, it left healthy cells alone. In lab tests, it spared astrocytes and neural stem cells while targeting tumor cells. For a cancer that has resisted nearly every treatment thrown at it, that selectivity mattered enormously.

It Crosses the Blood-Brain Barrier, and It Could Come as a Pill

Remember the blood-brain barrier, that biological shield keeping most drugs away from brain tumors? Li’s molecule crosses it. Where countless other potential brain cancer treatments have failed at this exact hurdle, Li’s compound apparently passes through with relative ease. And because of how the molecule behaves in the body, it could be delivered orally, taken as a simple pill rather than through intravenous infusion or injection.

In five different mouse models of glioblastoma, the molecule showed strong anti-tumor activity. It worked even against temozolomide-resistant tumors, meaning it could potentially help patients whose cancer no longer responds to existing chemotherapy. Across all five models, researchers observed no harmful side effects.

For a disease where the current best-case scenario involves brutal treatment regimens that buy only weeks, the idea of a patient swallowing a pill that targets only cancer cells while leaving healthy tissue alone sounds almost too good to be true. And to be clear, much work remains before that vision becomes reality. But the preclinical evidence is real, and it points in a direction that did not exist even a few years ago.

A Long Road Still Lies Between Lab Mice and Human Patients

Promising mouse studies do not automatically translate into human treatments. Li and his team know that better than anyone. Before their molecule could ever reach a pharmacy shelf, it must go through extensive optimization to ensure it behaves safely and effectively in the human body.

After optimization comes the long gauntlet of clinical trials, each phase testing the drug in an expanding number of human volunteers under strict FDA oversight. Only after passing through every stage would the compound earn approval as a treatment.

Li has taken concrete steps to push that process forward. He founded a company called AVIL Therapeutics to develop AVIL inhibitors. He and his colleague Zhongqiu Xie also obtained a patent related to this approach, signaling confidence that the science can make the leap from lab bench to clinic.

Research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Ben and Catherine Ivy Foundation has supported the work so far, and UVA’s Paul and Diane Manning Institute of Biotechnology aims to accelerate exactly this kind of translation from discovery to treatment.

Why Researchers Believe AVIL Could Rewrite the Playbook

What makes AVIL so appealing as a target goes beyond just one molecule or one study. It represents an entirely new mechanism of action, something glioblastoma treatment has never had. Every existing option attacks the cancer through broad, blunt approaches. AVIL offers the chance to hit a specific vulnerability that cancer cells depend on and healthy cells do not.

Other cancers have been tamed by targeting their specific oncogenes. Imatinib revolutionized treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia by going after a single genetic driver. Trastuzumab did something similar for certain breast cancers. Glioblastoma has never had its equivalent breakthrough, but AVIL could be the doorway.

Li’s team also believes their approach to gene discovery, starting with simpler pediatric cancers and following the trail into adult cancers, could yield similar results for other deadly diseases. What began as a study of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma has now produced a genuine candidate for treating the most aggressive brain cancer in existence.

“GBM patients desperately need better options. Standard therapy hasn’t fundamentally changed in decades, and survival remains dismal,” Li said. “Our goal is to bring an entirely new mechanism of action into the clinic — one that targets a core vulnerability in glioblastoma biology.”

For the thousands of patients who receive a glioblastoma diagnosis each year and are told nothing meaningful can be done, those words carry weight. A pill that crosses into the brain, kills cancer cells, and spares everything else is no longer just a fantasy. It is a molecule sitting in a lab, working its way toward the people who need it most.

Loading...