How a Small Asymmetry at CERN Points to Why Our Universe Exists

Why didn’t the universe erase itself the moment it began?

According to modern cosmology, the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of matter and antimatter. And when matter meets antimatter, the two annihilate into pure energy. If that balance had held perfectly, everything would have canceled out in the first fraction of a second.

But it didn’t. Matter survived. Galaxies formed. Stars ignited. Planets condensed. Life emerged.

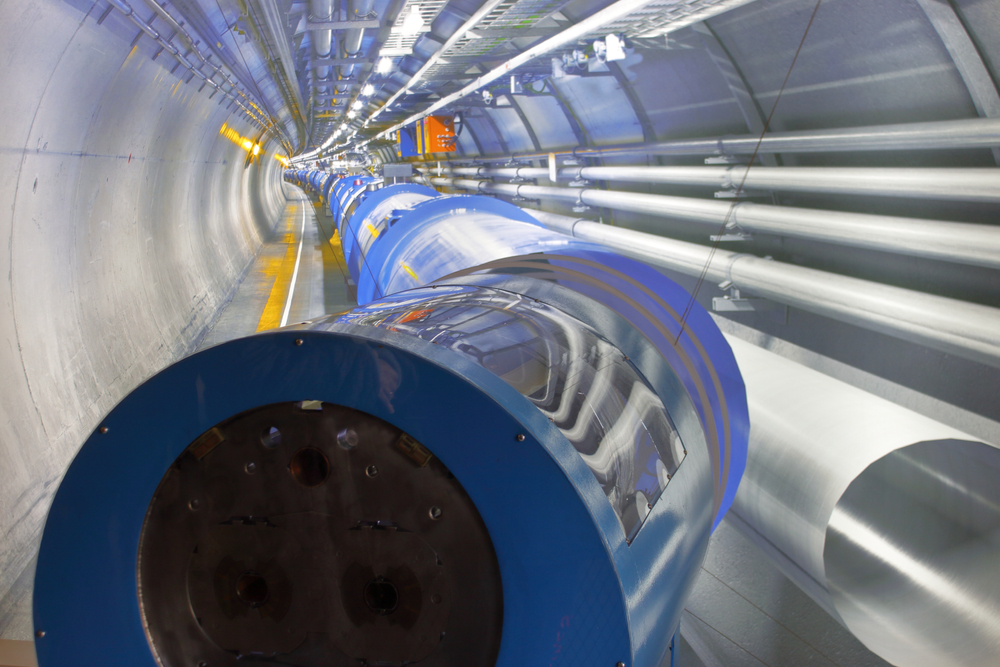

A new result from CERN, using the Large Hadron Collider, has revealed a subtle difference in how matter and antimatter behave in a class of particles called baryons — the very particles that make up the visible universe. The difference is small, but it may help explain why anything exists at all.

Let’s walk through what was discovered, why it matters, and what it could mean for our understanding of reality.

The Universe Should Have Canceled Itself Out

Matter particles have antimatter counterparts with the same mass but opposite electric charge. When they collide, they annihilate into energy. This is not theoretical — we observe it directly in laboratories.

Our best models of the early universe indicate that matter and antimatter were created in equal amounts during the Big Bang. If the laws of physics treated them perfectly symmetrically, every particle would have met its opposite and disappeared. The universe would be filled only with radiation.

Yet that’s not what we see. Everything around us — from atoms to galaxies — is made almost entirely of matter. Antimatter is extremely rare in the observable cosmos.

To account for the universe we inhabit, something must have tipped the balance in the earliest moments. For roughly every billion matter–antimatter pairs, one extra matter particle survived. That tiny excess is what built everything.

The question physicists have been asking for decades is simple: what caused that imbalance?

Where the Imbalance Shows Up in Real Matter

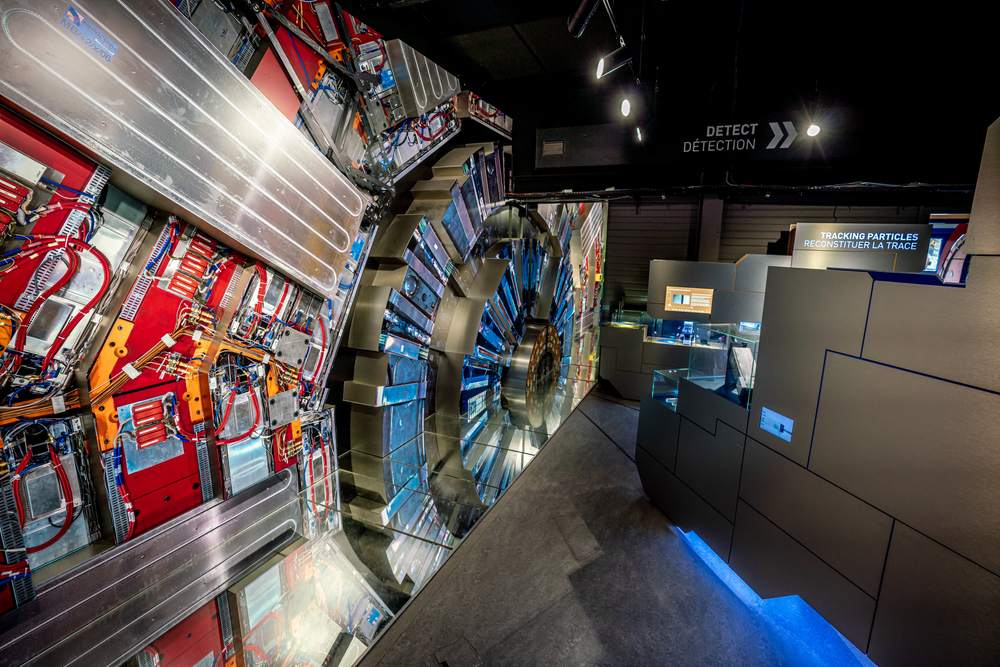

At CERN, one of the four major experiments at the Large Hadron Collider is called LHCb. Its specialty is studying differences between matter and antimatter with extreme precision.

In this recent measurement, scientists analyzed particles known as baryons. Baryons are composed of three quarks. Protons and neutrons — the building blocks of atoms — are baryons. That makes this class of particles especially important.

Previous experiments had already observed matter–antimatter differences in mesons, which are made of a quark and an antiquark. But this is the first confirmed observation of such a difference in baryons.

The team focused on a specific baryon called the lambda-b, which contains a beauty quark along with an up and a down quark. They compared how often these baryons decay into particular final particles versus how often their antimatter counterparts decay in the same way.

The result: matter baryons decayed about 5% more often than antibaryons in this specific process.

This difference is known as CP violation — a violation of charge-parity symmetry. In simple terms, it means the laws of physics are not perfectly identical for matter and antimatter.

The effect is small, but statistically solid.

The Subtle Law That Favors Matter

CP symmetry combines two transformations. Charge conjugation swaps particles with their antiparticles. Parity mirrors spatial coordinates. If CP symmetry were perfect, matter and antimatter would behave identically in all interactions aside from charge.

But nature doesn’t fully obey this symmetry.

CP violation was first observed in 1964 in mesons. Since then, experiments have measured it in several systems. The Standard Model of particle physics includes a built-in mechanism that allows for a small amount of CP violation.

Here’s the problem: the amount predicted by the Standard Model is far too small to explain the enormous matter dominance we observe today.

The new baryon measurement does not contradict the Standard Model. It fits within its predictions. But it extends CP violation into the very category of particles that dominate the visible universe.

That matters because any deviation from Standard Model expectations in future, higher-precision measurements could signal the presence of new physics — new particles or forces that existed in the early universe.

Small Differences, Cosmic Consequences

A 5% difference in a specific decay channel might sound minor. But early-universe physics operates under extreme conditions where even tiny biases can accumulate.

In the first microseconds after the Big Bang, particles and antiparticles were constantly forming and annihilating. If decay processes slightly favored matter, that imbalance could compound over time as the universe cooled.

What looks small in a laboratory measurement may translate into a decisive edge when scaled across trillions upon trillions of interactions.

This is why experiments like LHCb focus on precision. Physicists are not expecting dramatic breakdowns of known theory. They are searching for consistent, repeatable deviations — small cracks that reveal a deeper structure underneath.

The detector records millions of proton collisions per second, reconstructing decay pathways in detail. With future data runs, researchers expect to increase their dataset dramatically, allowing them to test the asymmetry with much higher precision.

If new discrepancies emerge, they could point toward particles or interactions not yet included in the Standard Model.

The Limits of the Standard Model

The Standard Model has been extraordinarily successful. It describes the behavior of known fundamental particles and three of the four fundamental forces. Its predictions have been repeatedly confirmed.

But it has clear limitations. It does not explain dark matter. It does not incorporate gravity. And it cannot account for the observed matter–antimatter imbalance.

Physicists suspect that additional particles may have existed in the early universe. These particles could have decayed in ways that strongly favored matter over antimatter, creating the imbalance required for structure to form.

Some proposals involve heavy, short-lived particles that no longer exist today. Others look to neutrino behavior or early-universe phase transitions. The challenge is finding experimental evidence that distinguishes these ideas from established theory.

Measurements like the recent baryon CP violation result are part of that effort. They provide new terrain where theory can be tested against observation.

Why a Slight Imbalance Created Everything

This discovery doesn’t solve the mystery of why the universe exists. But it tightens the framework.

For the first time, we have confirmed CP violation in baryons — the particles that make up everyday matter. That extends asymmetry into the very foundation of the physical world.

Existence depends on imbalance. If matter and antimatter had behaved perfectly symmetrically, the universe would have remained a sea of radiation. No atoms. No stars. No chemistry.

The fact that we are here means that, at the most fundamental level, reality is not perfectly symmetrical.

Physics often begins with symmetry principles. But the universe we observe includes small violations of those symmetries. Those violations are not errors. They are part of the structure of nature.

A slight preference in subatomic decay processes billions of years ago may be the reason galaxies exist today.

Closing in on the Origin of Matter

The LHCb experiment will continue collecting data at higher intensities. As datasets grow, researchers will probe rarer decay channels and look for deviations from Standard Model predictions.

If they find none, the puzzle deepens and the search expands to other sectors of physics. If they find even a small discrepancy, it could reshape our understanding of the early universe.

The question driving all of this remains straightforward: why is there something rather than nothing?

CERN has not answered that question yet. But by identifying a measurable asymmetry in the particles that form ordinary matter, it has narrowed the search.

The universe may exist because the laws of physics contain a slight built-in bias. Not dramatic. Not obvious. But enough.

And in a cosmos where one extra particle in a billion changed everything, small differences are not small at all.

Featured Image Source: Shutterstock

Loading...