The Surprising Alliance Changing the Future of Animal Research

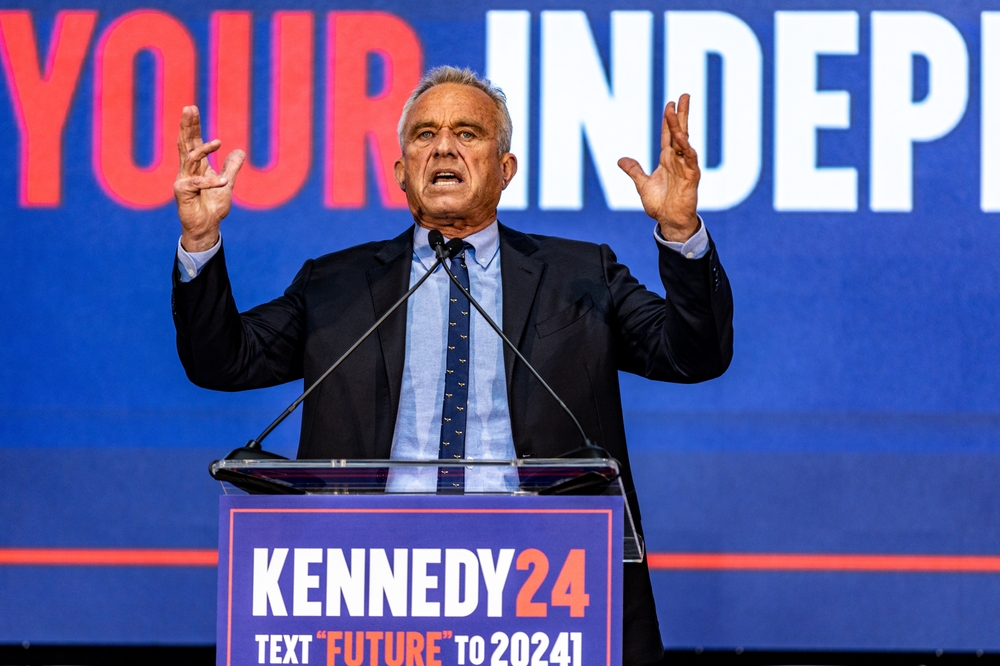

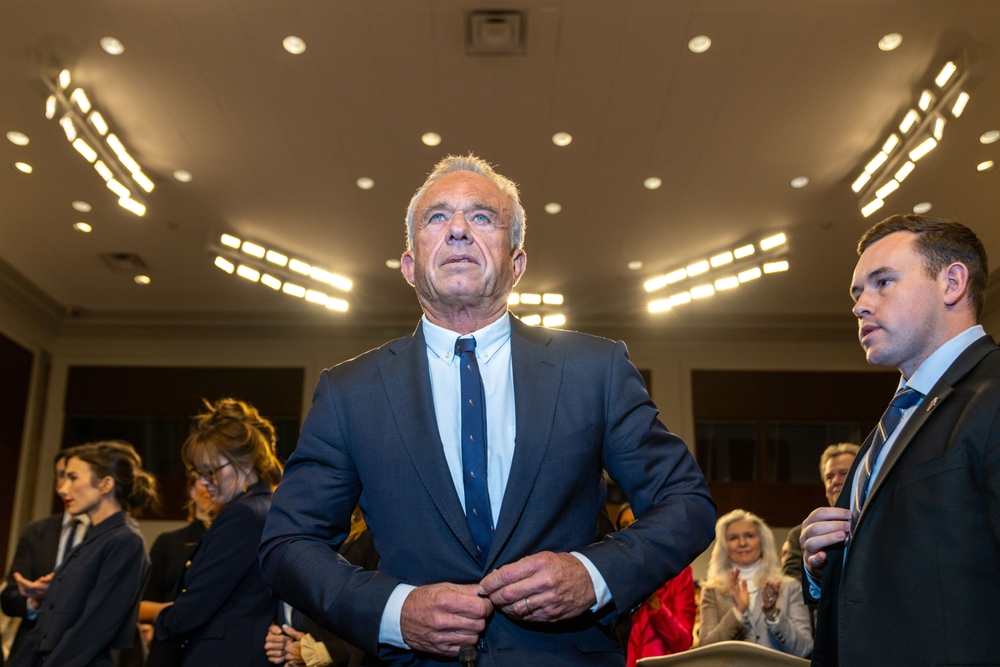

The idea that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Donald Trump would one day find themselves on the same side of an ethical debate might have sounded implausible only a few years ago. Yet, in a country as politically polarized as the United States, the movement to end animal testing has done something almost unimaginable: it has united figures and factions that rarely share a stage. The new alliance, rooted in Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) initiative, is reshaping the conversation around science, ethics, and government policy.

What began as a campaign promise to modernize the American health system has become a moral and political experiment. At its center lies a question that transcends partisanship: can compassion and scientific progress coexist in modern policymaking?

A Post-Biden Era Battle Over Sunscreen and Science

When Kennedy was appointed Secretary of Health and Human Services, one of his earliest challenges came in the form of an obscure but revealing policy inherited from the Biden administration. The Food and Drug Administration had introduced a plan to test certain sunscreens and cosmetics on animals to study the potential absorption of chemicals through the skin. Animal rights advocates, including PETA President Ingrid Newkirk, condemned the move as a step backward from decades of progress.

Senator Cory Booker had already criticized the testing mandate before leaving office, calling it “an unnecessary return to cruelty.” PETA went further, warning that it would remove sunscreen from its Beauty Without Bunnies list, a guide for consumers who avoid products tested on animals. The group urged Kennedy to cancel the requirement, appealing to his campaign statements in which he had promised to oppose cosmetic animal testing.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is pushing to end all animal testing for chemicals and drugs in the U.S., calling it a moral and scientific imperative. 🙏🐇

— dominic dyer (@domdyer70) October 29, 2025

As part of his Make America Healthy Again initiative, Kennedy has directed federal agencies to shift toward alternatives like… pic.twitter.com/ltE5Ki45G0

Kennedy found himself in a delicate position. As a long-time critic of bureaucratic inefficiency, he shared Newkirk’s disdain for wasteful research practices. Yet he also faced pressure from regulatory agencies steeped in decades of animal-based testing methods. The question was not only ethical but economic. Newkirk argued that eliminating the tests could save millions of dollars and align with the Trump administration’s broader effort to trim government waste.

“RFK Jr. and the prospective FDA commissioner have both spoken and written extensively about the wastefulness of the FDA’s bureaucracy,” she said. “The sunscreen testing requirement is exactly the kind of burdensome regulatory bureaucracy that both of those people need, and want, to eliminate.”

Her words struck a chord. For Kennedy, it was a chance to demonstrate that moral progress and fiscal conservatism could be partners rather than rivals. For the Trump administration, it was an opportunity to show compassion without compromising its commitment to cutting red tape.

The Rise of the MAHA Initiative

The Make America Healthy Again initiative soon became the umbrella for a much broader movement. Its goal was to modernize American biomedical research, not merely by ending animal testing but by promoting human-based alternatives such as organoid models, artificial intelligence simulations, and computer-based toxicity testing.

In early 2025, the National Institutes of Health announced the creation of the Standardized Organoid Modeling Center, an 87-million-dollar project designed to replace animal experiments with advanced human cell systems. These organoids, clusters of cells that mimic the structure and function of organs like the heart, liver, or brain, promise to deliver results that are more accurate, faster, and more humane.

Kennedy described the center as “a bridge between ethics and innovation.” The language was striking. It positioned the administration not as an opponent of science, but as its reformer. This approach, blending technological enthusiasm with moral purpose, helped the movement gain supporters from across the political spectrum.

Emily Trunnell, PETA’s director of science advancement, called the initiative a turning point. “About a month ago, we sent NIH several examples of wasteful grants involving animal research. Anybody could look at what was being done to monkeys and dogs and say, there’s no way taxpayers should be funding this. We’re finally seeing a government willing to question that.”

This unusual alliance between PETA and the Trump administration was reinforced by another group: the White Coat Waste Project, a conservative watchdog organization that had long opposed taxpayer-funded animal experiments. Its founder, Anthony Bellotti, said his group was “thrilled that the Trump administration is putting wasteful animal experiments under the microscope.” Polling conducted by the group showed that 85 percent of Americans, across party lines, oppose using public money for such experiments.

For once, activists on the left and fiscal hawks on the right were not arguing they were nodding in agreement.

The Science and Morality of Reform

Kennedy’s argument for ending animal testing is not only moral but deeply scientific. He often cites a sobering statistic from the FDA: roughly 90 percent of drugs that pass animal testing fail in human trials. In other words, animal studies are often poor predictors of how substances will behave in human bodies.

“We’re spending billions on research that doesn’t deliver results,” Kennedy said in a recent address. “We can do better, for science, for health, and for animals.”

Supporters of the initiative call this “ethical modernization,” the idea that moral progress and scientific accuracy can reinforce one another. By replacing animal models with organoids and AI simulations, researchers can test drugs using systems that replicate human biology more faithfully. Kennedy’s department has begun funding grants that cover the rehousing of laboratory animals, allowing them to live out their lives rather than being euthanized after experiments.

The new policy is as much philosophical as it is practical. It challenges the century-old assumption that human health must depend on animal suffering. It also questions the inertia of scientific tradition. As Kennedy’s ally at the NIH, Director Jay Bhattacharya, put it, “This is not a rejection of science but a restoration of it. For too long, we’ve mistaken habit for evidence.”

A Bipartisan Coalition Takes Shape

What makes the MAHA initiative remarkable is not only its content but its coalition. The partnership between Trump, Kennedy, PETA, and the White Coat Waste Project would have seemed impossible a decade ago. Historically, animal rights advocacy was associated with the political left, while conservatives emphasized economic efficiency and scientific freedom. Yet the fight against animal testing has blended these values into a single narrative.

According to political scientist Alfred Runte, this convergence may even signal a new kind of political strategy. “Most animal rights activists tend to be leftists,” he observed. “If RFK can make believers out of people who don’t want so much animal testing, that could bring more liberals into the Republican fold.”

There are signs this may already be happening. Younger voters, particularly those concerned with sustainability and cruelty-free consumerism, have responded positively to the administration’s messaging. Animal welfare, once dismissed as a niche cause, now serves as a moral bridge between generations and ideologies.

Trump’s political advisers see this as more than good optics. One campaign strategist told Politico, “It softens his image without changing his brand.” Supporting humane science allows the former president to appeal to moderates and independents while staying true to his populist narrative of reforming wasteful government practices.

The Economic Case for Humane Science

Beyond ethics and politics, the movement carries significant economic implications. Animal testing is expensive, slow, and often redundant. It supports a large industry of animal suppliers, breeders, and contract laboratories. Shifting toward human-based research threatens these entrenched interests but also promises to reduce costs dramatically.

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, a Johns Hopkins surgeon and author selected by Trump to lead the agency, has championed reforms that align with this vision. Under his leadership, the FDA has introduced measures to streamline drug approval processes and reduce unnecessary testing. One focus has been the development of biosimilars, cheaper generic versions of complex biologic drugs that could lower healthcare costs nationwide.

Makary believes that reforming outdated testing requirements is key to breaking what he calls the “biologics bottleneck.” Currently, biologic drugs account for just five percent of prescriptions but more than half of total drug spending in the United States. Allowing faster approval and human-based testing, he argues, could cut development time in half and save billions of dollars.

Kennedy has described the current system as a “hostage crisis,” where outdated laws keep drug prices artificially high. By eliminating redundant animal tests, the MAHA initiative fits neatly into the administration’s broader promise to make healthcare more affordable and efficient.

Critics and Caution

Not everyone in the scientific community is convinced. Some researchers warn that eliminating animal models entirely could endanger patient safety. Naomi Charalambakis, a policy expert at Americans for Medical Progress, argues that organoids and AI systems still cannot replicate the complexity of whole organisms. “They can’t yet reproduce the immune system, metabolism, or long-term toxicity effects that we see in animals,” she said.

Kennedy’s team acknowledges these limitations. The transition, they insist, will be gradual and evidence-based. The NIH has prioritized replacing animal testing first in areas where it is least predictive, such as toxicity screening and neurological studies. The agency plans to expand the use of organoid and AI-based systems as they mature.

The debate also carries an economic undercurrent. The animal testing industry employs thousands of workers and generates billions in revenue. Any large-scale transition will require careful retraining, investment in new infrastructure, and revised regulatory frameworks. Yet Kennedy and Makary argue that these costs are temporary. The long-term gains, they believe, lie in the creation of a more ethical, efficient, and globally competitive biomedical sector.

A Global Trend Toward Humane Research

The United States is not alone in rethinking animal testing. Across the Atlantic, the European Union has already committed to phasing out such practices in safety studies by the end of the decade. Several European countries, including the Netherlands, have invested heavily in human-based research technologies. The United Kingdom and Canada are following similar paths, creating international momentum for what some are calling the “humane science revolution.”

The U.S. Congress laid the groundwork for this shift with the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, passed in 2022, which ended the federal requirement that new drugs must be tested on animals before human trials. The Trump administration’s policies build upon that legislation, transforming it from principle into practice.

According to HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon, “Whether through AI-driven models, organoid technology, or other innovative tools, we’re seeing a shift toward safer, more ethical, and more efficient methods of testing. This is an issue that bridges ideology because it’s about modernizing science while aligning it with our values.”

The Politics of Compassion

Political observers have described the alliance between Kennedy and Trump as both pragmatic and symbolic. For Trump, embracing humane science helps rebrand his movement as forward-looking rather than combative. For Kennedy, it fulfills a personal and philosophical mission. His family’s long history of activism has often placed him at the intersection of science, health, and moral reform.

In speeches, Kennedy avoids framing the issue in partisan terms. “This isn’t about left or right,” he told an audience at the SOM Center’s opening. “It’s about doing what’s right and what works.” The line has become something of a mantra for the MAHA initiative, reflecting its unusual coalition of activists, scientists, and politicians.

Trump’s advisors, meanwhile, see in the movement an opportunity to appeal to voters disillusioned with political extremism. In a time when environmental and ethical concerns often polarize the electorate, animal testing offers a rare area of consensus.

A Future Beyond the Lab Cage

Ending animal testing will not happen overnight. It will require new infrastructure, extensive training, and regulatory patience. But progress is visible. The SOM Center has begun producing standardized organoid models for national use. Universities are updating their ethics guidelines, and researchers are shifting funding proposals toward human-based methodologies.

For Kennedy, this is only the beginning. He envisions a research ecosystem where innovation and empathy coexist, where taxpayer dollars fund discovery without cruelty, and where America leads the world in humane science. His vision extends beyond laboratories to the cultural heart of modern science itself.

The transformation also raises profound philosophical questions. If compassion becomes a guiding principle in science, what other long-accepted practices might be reconsidered? How will this affect the definition of progress? Kennedy’s allies see this as a long-overdue moral correction. His critics worry it could blur the line between science and sentiment.

Yet for all its complexities, the movement represents something rare in today’s politics: a shared moral horizon. By linking efficiency with empathy, Kennedy and Trump have created an unlikely blueprint for reform that appeals across ideologies.

Toward an Ethic of Progress

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s campaign to end animal testing has achieved something few policies can claim it has redefined what it means to be both ethical and pragmatic in government. Supported by President Trump and groups as ideologically distant as PETA and the White Coat Waste Project, the MAHA initiative stands as proof that compassion need not be a partisan value.

Whether or not the movement succeeds in ending animal testing entirely, it has already shifted the national conversation. It invites Americans to imagine a future where moral conscience and scientific precision advance together, rather than in opposition. It challenges both the laboratories of science and the laboratories of politics to evolve.

As Kennedy said at the SOM Center’s opening, “Our health system can’t claim to be humane while it depends on cruelty. The path to better science begins with empathy.”

If that vision endures, this unlikely alliance between Kennedy and Trump may be remembered not just as political theater but as the moment when American science began to measure its progress not only by what it discovered but by what it refused to harm.

Loading...