Science Is Revealing That Life Does Not End All at Once

For most of our lives, we are taught that death is a full stop. One moment the body works, the next it does not, and the story is over. Medicine, culture, and even language reinforce the idea that life shuts off cleanly and completely.

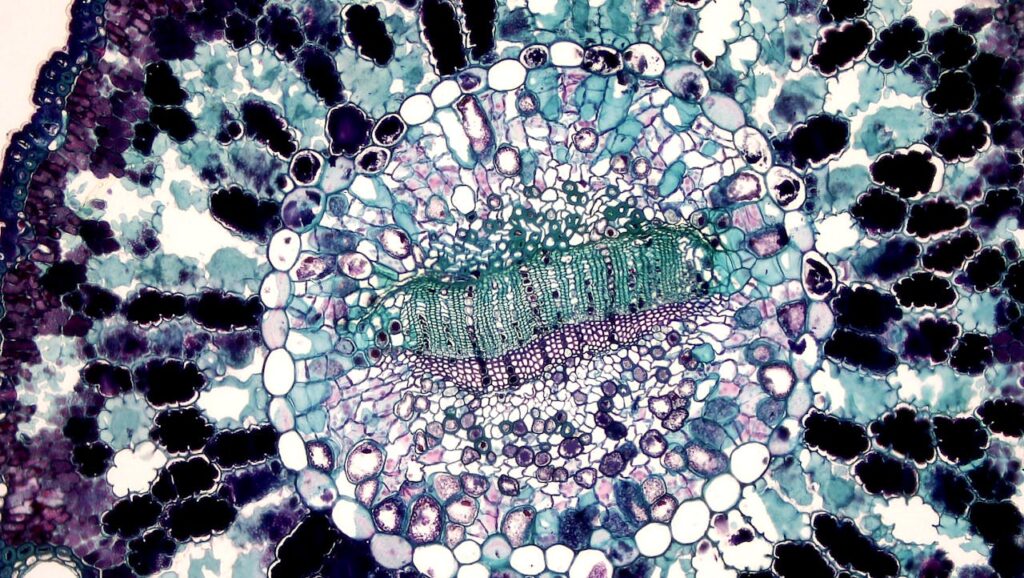

But recent research is beginning to complicate that belief. At the smallest scales, life does not always obey the rules we expect. Some cells continue to respond, reorganize, and act with purpose even after the organism as a whole has stopped functioning. Scientists are now observing behavior that sits outside our usual definitions of alive or dead, a space that challenges how final an ending really is.

This is not speculation. These findings come from peer reviewed studies and are already influencing how researchers think about regeneration and biological intelligence. And once you realize that life may not end everywhere at the same time, it becomes harder to ignore the question that follows. What else have we assumed was finished when it was only changing form.

The Body Ends, But Not All Life Does

When science declares someone dead, it is talking about the body as a system. The heart stops circulating blood. The lungs stop moving oxygen. The coordination that once held trillions of cells together collapses. But that definition applies to the organism, not to every cell inside it. Long after the system fails, many cells continue doing what they were built to do, adapting moment by moment to what remains of their environment.

We already rely on this reality more than we realize. Organ transplants are possible because tissues can stay viable for a window of time after death when oxygen loss is controlled. Skin grafts and bone marrow transplants work because certain cells can survive separation and resume function in a new setting. Cryopreservation pushes this even further by slowing cellular activity so dramatically that tissues can be stored for years and later return to life. Modern medicine is built on the quiet truth that death does not arrive everywhere at once.

What newer research reveals goes deeper than survival alone. Some cells do not simply linger and fade. They adjust. Studies examining gene activity after death show that certain stress and immune related genes become more active for hours or even days. Instead of shutting down uniformly, cells respond to their changing surroundings. They are not conscious and they are not alive in the human sense, but they are not passive either. Even in the absence of the body that once organized them, they continue to react, reminding us that life is not a single switch, but a layered process that unwinds over time.

When Rules Fall Away and Possibility Emerges

Most of what we know about life comes from watching it follow rules. Cells develop along familiar paths, guided by genetic instructions and reinforced by constant signals from the body around them. A frog embryo becomes a frog. Human skin cells stay focused on protection and structure. Order is maintained because the system is intact and every part knows its role.

But what happens when that system is no longer there. When cells are removed from the environment that once defined them, the instructions do not disappear, but their influence changes. Without the organizing pressure of the full organism, cells are no longer locked into the same developmental script. They begin responding more directly to local conditions and to each other, rather than to a central authority.

Researchers have observed that cells taken from deceased organisms can do more than survive. In controlled settings, groups of cells have been seen organizing themselves into stable structures, coordinating movement, and performing functions unrelated to their original role. No genes were altered. No external design was imposed. The behavior emerged from interaction, cooperation, and responsiveness to a new context.

This challenges how we categorize life. These cells are not becoming new organisms, and they are not reproducing in any traditional sense. Yet they are not falling apart either. They exist in a state where activity continues without a body wide system directing it. What this reveals is not a loophole in biology, but a deeper truth. Life is capable of reorganizing itself when familiar boundaries dissolve, and sometimes, what looks like an ending is actually a shift into a different way of functioning.

When Ordinary Cells Begin Solving Problems

In a frog embryo, skin cells live predictable lives. They serve the surface, move fluid, and follow instructions handed down by the developing body. They are not leaders, explorers, or builders. For a long time, scientists assumed that once these cells were removed from that environment, their usefulness would end with it.

What researchers discovered challenged that assumption. In laboratory experiments using skin cells from African clawed frog embryos, the cells did not scatter or lose function when separated from the organism. Instead, they came together. Without genetic modification and without external design, they formed small, stable multicellular structures that researchers later named xenobots. These structures were not planned in advance. They emerged from cells interacting with one another under new conditions.

In this unfamiliar setting, the cells began using their cilia in a coordinated way that allowed the entire structure to move across a surface. Inside the embryo, those same cilia served a very different purpose. Here, they became a tool for collective motion. The behavior was not engineered or instructed. It arose naturally once the usual developmental constraints were removed.

Further experiments revealed something even more surprising. These structures could gather loose cells from their surroundings and assemble them into new xenobots with similar shape and behavior. This did not involve growth or cell division and did not resemble reproduction as biology normally defines it. Michael Levin, one of the scientists involved in the research, has explained that none of this behavior was explicitly programmed. The cells followed basic biological rules, and when the environment changed, new possibilities emerged.

Why Some Cells Continue After the Body Stops

The research does not suggest that all cells survive after death, nor does it imply that survival happens by chance. What scientists have observed is that cellular persistence follows clear biological rules. Cells with lower energy demands are better able to tolerate the loss of blood flow because they consume stored resources more slowly. Environmental conditions also play a measurable role. Cooler temperatures, reduced dehydration, and limited access to oxygen or nutrients can significantly extend how long certain cells remain viable after the organism has died.

The type of cell involved is one of the strongest factors. Highly specialized cells such as neurons require constant energy and tightly regulated conditions, which makes them among the first to fail. Other cells are built for durability. Fibroblasts and cells with stem like characteristics are more adaptable and better equipped to withstand stress. Studies reflect this difference clearly. Human white blood cells have been shown to remain viable for several days after death. In animal models, skeletal muscle cells have been regenerated more than a week later, and fibroblasts from livestock have been successfully cultured weeks after death under controlled conditions.

Researchers are also investigating why these cells retain function rather than breaking down immediately. One explanation centers on bioelectric signaling. Even after organism level coordination ends, ion channels and membrane pumps can continue maintaining electrical gradients across cell membranes. These electrical patterns allow cells to communicate locally and preserve basic organization. The study findings point to a consistent conclusion. Cellular survival after death is not mysterious or random. It is governed by measurable biological mechanisms that allow some cells to remain structured and responsive even when the larger system that once unified them is gone.

What This Research Teaches Us About Focus and Drive

One of the most important lessons from this research is that function depends on conditions. Cells that remain active after death do so not because they are extraordinary, but because their environment supports their basic needs. Energy use is balanced. Stress is reduced. Communication remains intact. When those conditions collapse, function fades. The same principle applies to human focus and motivation. Clarity and drive are not just products of willpower. They emerge when the systems that support attention and energy are given what they need to operate well.

Modern life often demands constant output while ignoring the conditions that make sustained effort possible. Poor sleep, chronic stress, and constant distraction disrupt the signals that keep the body and brain coordinated. Research in physiology and neuroscience consistently shows that focus improves when the nervous system is regulated, energy demands are managed, and recovery is prioritized. Just as cells with lower metabolic strain persist longer, people who pace their effort and protect their energy tend to maintain motivation more consistently over time.

This research also reframes achievement as a collective process rather than a solo act. Cells function best when communication is clear and coordination is preserved. For individuals, this translates into aligning habits, environment, and mindset toward the same goal. Reducing unnecessary friction, creating routines that support attention, and allowing time for restoration are not signs of weakness. They are strategies rooted in how life sustains itself. When the conditions are right, effort feels less forced, focus becomes steadier, and motivation stops being something you chase and starts being something that naturally arises.

The Conditions That Keep Us Moving

This research makes one thing clear. Function does not disappear all at once. It fades when the conditions that support it fall apart. Cells persist when energy is managed, stress is reduced, and communication remains intact. When those supports are lost, even the most complex systems fail. Life responds to its environment long before it responds to intention.

For personal growth, this shifts the focus away from force and toward structure. Motivation and focus are not traits you either have or lack. They are outcomes of how well your inner systems are supported. When you protect your energy, reduce unnecessary strain, and create conditions that allow steady coordination, progress becomes more sustainable. Achievement stops being about pushing harder and starts being about building the right foundation to keep going.

Featured Image from Shutterstock

Loading...