Scientists Discover Mutated Brains in Stranded Dolphins — and the Cause Could Threaten Us To

When dolphins, the joyful emblems of intelligence and grace, begin washing ashore with brains ravaged by the same biological chaos that steals human memory, the story stops being about them. It becomes about us. Along Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, scientists have discovered something deeply unsettling: dolphins are showing signs of Alzheimer’s-like brain damage, their neural pathways tangled and misfolded, their memories, if they hold them like we do, perhaps dissolving before they die. And what’s destroying their minds isn’t a mystery virus or natural aging. It is a toxin born from something we created, something that traces directly back to the way we live and manage our world.

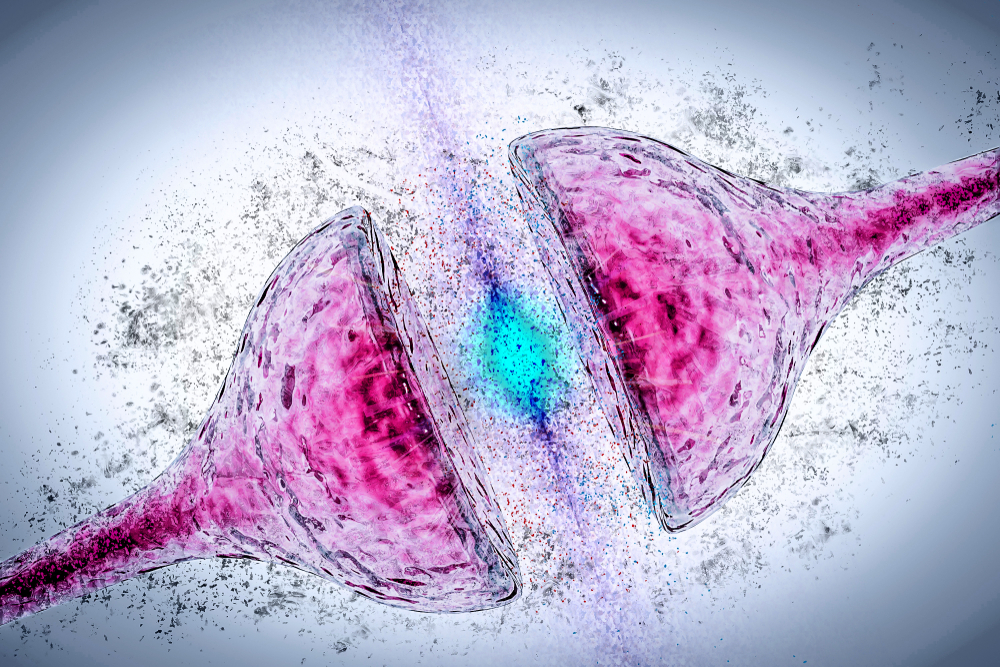

The blue green bloom beneath the surface

The culprits are cyanobacteria, often called blue green algae. They thrive in warm, nutrient rich waters, exactly the kind that human industry has been perfecting for decades. Agricultural runoff, sewage leaks, and fertilizer waste feed these blooms, turning clear water into thick, neon green soup. And while it looks almost beautiful from a distance, it hides one of nature’s most efficient assassins, a silent army of microscopic organisms capable of changing the chemistry of life itself.

These bacteria release compounds such as BMAA (β N methylamino L alanine), 2,4 DAB (2,4 diaminobutyric acid), and AEG (N 2 aminoethylglycine), chemicals that silently attack nerve cells. Over time, they cause the same kind of protein misfolding and plaque buildup seen in Alzheimer’s disease, clogging the brain with sticky amyloid plaques and twisted tau proteins that choke communication between neurons. When researchers examined the brains of 20 bottlenose dolphins stranded between 2010 and 2019, they found the results shocking. Dolphins that washed ashore during peak algae blooms had up to 2,900 times more 2,4 DAB in their brains than others. Every single dolphin showed the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s, from protein tangles to damaged gene pathways linked to neurodegeneration. The creatures we once admired for their intelligence were dying with brains eerily similar to those of elderly patients in nursing homes.

Dolphins as environmental mirrors

Dr. David Davis of the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine described dolphins as environmental sentinels for toxic exposures in marine environments. In other words, they are not just victims, they are warnings. What happens in their waters often foreshadows what may happen in ours. Their suffering mirrors the state of our ecosystems, and in a way, reflects our future if we fail to listen.

This connection is not speculation. Studies on human populations have shown that chronic exposure to cyanobacterial toxins can cause similar brain damage. In Guam, for example, communities that consumed foods contaminated with cyanobacteria developed neurodegenerative conditions nearly identical to Alzheimer’s. Laboratory experiments confirmed the pattern, showing that animals exposed to these toxins exhibited memory loss, brain lesions, and behavioral confusion. And now, Florida appears to be moving down the same path. Miami Dade County, surrounded by waterways increasingly plagued by algae blooms, recorded the highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States in 2024, a statistic that can no longer be dismissed as coincidence.

The human fingerprint in the lagoon

Cyanobacteria are ancient organisms, older than dinosaurs, older even than trees. But the frequency and scale of their toxic blooms are distinctly modern. Human driven climate change, nutrient pollution, and water mismanagement have made conditions ideal for these microorganisms to thrive. Each summer, as temperatures rise, blooms spread across Florida’s waters, coating once clear rivers and estuaries in a chemical haze. Lake Okeechobee, once called the liquid heart of Florida, now releases toxic water into rivers like the St. Lucie and Indian River Lagoon. These discharges carry vast quantities of cyanobacteria downstream, suffocating marine life and poisoning habitats that once teemed with color and movement.

For dolphins, creatures who rely on sonar, intelligence, and complex communication, swimming through these waters means constant exposure to invisible poisons. This is bioaccumulation at work, a process that concentrates toxins at the top of the food chain. Small fish ingest microscopic toxins. Larger fish eat those fish. Then come the dolphins, swallowing not just prey but decades of our chemical neglect. Their bodies become living records of our environmental disregard. Their brains, in many ways, are becoming the archives of our story, carrying the molecular scars of humanity’s choices.

Memory as a shared inheritance

Memory, that fragile and luminous network that defines who we are, is not just a human treasure. Dolphins, with their complex social behaviors and lifelong bonds, also depend on memory for survival. They remember the contours of the ocean floor, the songs of their pods, and the routes their ancestors once swam. They share knowledge through generations, passing wisdom through sound and experience. When toxins erase their memories, they lose not only navigation but culture itself. Imagine an entire species forgetting its language, its identity, its way home.

Now, scientists suspect these same toxins might be eroding ours. While Alzheimer’s disease likely has multiple causes, including genetic, metabolic, and environmental factors, cyanobacterial exposure is emerging as a serious risk factor. In this way, the dolphins’ tragedy becomes our prophecy. It is a mirror held up to our collective actions, asking whether we are willing to learn before it is too late. The ocean’s memory, after all, is also our own.

Lessons from the lagoon, what we can do

It is easy to feel powerless in the face of such vast and invisible dangers. But every toxic bloom starts with something tangible, something within our control: runoff, pollution, warming water. Each of these can be traced, mitigated, and changed. Reforming water management is one of the most urgent steps. Florida’s system of releasing polluted lake water into coastal rivers is outdated and devastating. Sustainable management practices, such as improved filtration wetlands and stricter nutrient caps, are essential to protect both marine and human life.

Agriculture plays an equally important role. Farmers can use cover crops, buffer zones, and reduced fertilizer application to cut nutrient leakage into waterways. Meanwhile, governments and citizens alike must invest in climate resilience, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and protecting natural wetlands that filter pollutants before they reach open water. Supporting environmental monitoring, through local initiatives and citizen scientists, can help track bloom severity and provide early warnings to communities and wildlife managers. Most importantly, we must choose awareness over apathy. The smallest acts, from supporting clean water policies to reducing waste and voting for environmentally conscious leaders, create ripples that reach far beyond our sight.

Reflection, remembering what matters

We often think of the environment as something outside ourselves, a landscape, a backdrop to human activity. But the truth is far deeper. What poisons the dolphin’s brain poisons our own potential. What clouds their memory also clouds our collective future. The dolphins of Florida are not simply dying; they are speaking. Their stranded bodies whisper a truth we have tried too long to ignore, that nature remembers what we forget. If we want to keep our memories, our stories, our families, our humanity, we must learn to protect theirs first.

Loading...