Sperm Cells Carry Traces of Stress Experienced by a Father, New Study Shows

What if the pain you carried as a child didn’t end with you?

Not just in the memories you’ve tucked away or the habits you’ve tried to outgrow—but in your biology. In the cells that carry your story forward, even before a child is born.

New research is now telling us something many of us have felt, but couldn’t quite explain: that trauma experienced by fathers in childhood may leave measurable traces in their sperm. These aren’t just emotional imprints—they’re molecular. Small chemical markers, quietly etched into the fabric of life’s blueprint.

This means that a father’s early life experiences could influence the development of his children, not through parenting alone, but through biology. The study, published in Molecular Psychiatry, challenges how we think about inheritance, responsibility, and healing. It forces us to consider that legacy isn’t just what we pass down in stories—it might also live in our cells.

This isn’t about blame. It’s about understanding. Because when we recognize how deep the roots go, we can finally begin to change what grows from them.

Your Past, Under a Microscope

Scientists have long understood that our experiences can shape our behavior, our worldview, and even our health. But new research suggests that these experiences—especially those from early in life—may leave traces in places we wouldn’t expect: in the cells that create life itself.

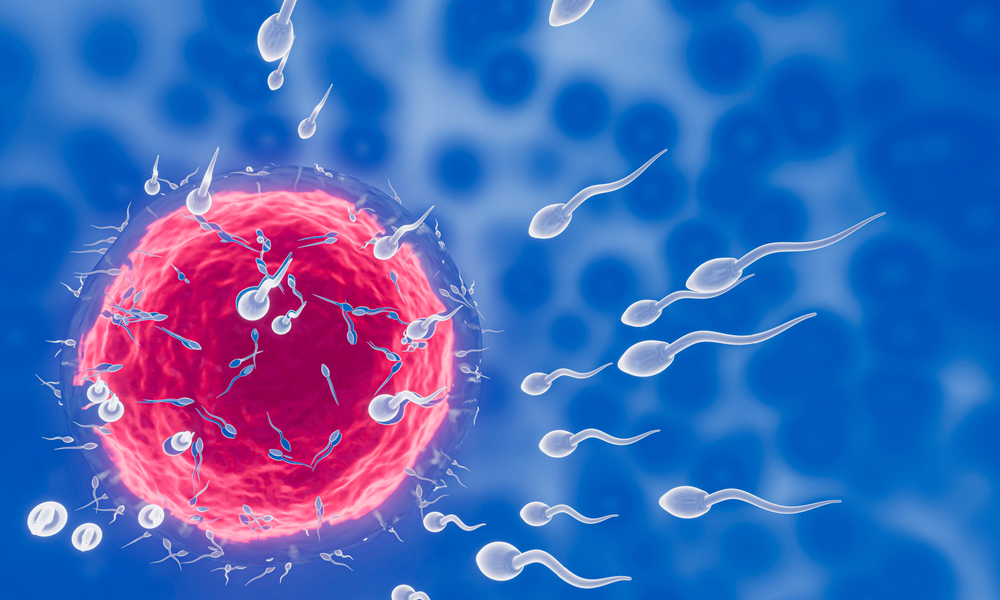

A recent study published in Molecular Psychiatry examined sperm samples from 58 adult men, most in their late 30s and early 40s. The participants were asked to reflect on their childhoods, focusing in particular on any adverse experiences they had faced, such as emotional neglect, physical abuse, or other forms of trauma. The goal of the study was to determine whether the psychological stress endured in youth could have a biological impact later in life—specifically, in their sperm.

The findings were significant. Men who reported high levels of childhood stress showed distinct differences in their sperm’s epigenetic profile compared to those with lower reported stress. These differences were not linked to lifestyle factors like smoking or alcohol use; they were specifically associated with early life experiences.

What the researchers observed were changes in DNA methylation patterns and levels of small noncoding RNAs—molecular signals that regulate how genes are expressed. These are not mutations in the DNA itself, but chemical modifications that influence how that DNA behaves. Some of the altered markers were found near genes involved in brain development, raising the possibility that a father’s early trauma could influence the neurological development of his future children.

This area of study falls under the field of epigenetics, which examines how environmental influences can modify gene expression without changing the DNA sequence. In simple terms, while the genetic code remains the same, the way it is read and acted upon can shift depending on life experiences.

The study does not claim that these changes are guaranteed to be passed on to the next generation. Rather, it highlights the potential for such a connection, and invites us to take seriously the idea that trauma can reach beyond the person who experiences it.

Inheritance Isn’t Always Genetic

When we think about what gets passed from parent to child, we often focus on the obvious—eye color, height, maybe a particular smile or the way someone laughs. But some inheritances run deeper. They aren’t visible in photographs or obvious in family trees. They live in the body. And sometimes, they begin in silence.

The idea that trauma can leave a mark on the body isn’t new. What’s new is where we’re now finding those marks—and how far they might travel. The changes observed in the sperm cells of men who endured early life stress don’t simply sit idle. Many of the altered molecular signals, such as DNA methylation and small RNA activity, are found near genes related to brain development. That’s not a coincidence. It suggests a possible biological link between a father’s unresolved past and the mental or emotional health of his future children.

This isn’t theory—it’s a measured, documented possibility. As Dr. J.J. Tuulari, one of the study’s lead authors, explained, “Our findings suggest that childhood adversity may be biologically embedded in germ cells and potentially affect the next generation.”

To be clear, the study does not confirm that these epigenetic changes are directly inherited. There are still many questions to answer. But what it does show is that our bodies keep score—especially when the mind tries to forget. Stress doesn’t just disappear. It may shift form. From memory into biology. From father to child.

The Power of Choice: Can We Rewrite the Story?

If stress can shape our biology, then so can healing. This is where the science of epigenetics offers not just insight, but hope. The study of how experiences shape gene expression has uncovered a powerful truth: while past hardships may leave their imprint, they do not cement our fate. Just as a father’s childhood stress may write invisible notes into his DNA, positive life changes can rewrite the script. The body is not static—it is constantly adapting, responding, and evolving. And the same way stress can switch certain genes on or off, so can resilience, love, and conscious well-being.

Studies have already shown that lifestyle choices, such as exercise, meditation, therapy, and healthy relationships, can influence epigenetic patterns. In fact, research on trauma survivors suggests that healing practices can reverse some of the negative epigenetic changes caused by stress. In essence, just as past wounds can leave scars at a molecular level, intentional efforts toward mental and emotional well-being can begin to erase them. This means that a father’s story doesn’t have to be one of inherited struggle—it can be one of transformation.

But this shift doesn’t happen automatically. It requires awareness, intention, and action. Men, particularly fathers, are often conditioned to endure stress in silence, to be the unshakable pillars of strength in their families. Yet, this research underscores the reality that taking care of mental health isn’t just about personal well-being—it’s about breaking cycles that could impact future generations. Healing is no longer just an individual act; it is an act of generational change.

So, the real question isn’t just whether stress leaves a mark—it’s whether we will choose to rewrite the story. Every choice matters. The way we handle stress, the way we process pain, the way we care for ourselves—all of it has the potential to shape not just our lives, but the lives of those who come after us. This is not about fear; it’s about empowerment. Because while the past may whisper into our biology, the future is still ours to shape.

Breaking Generational Patterns

Understanding that stress leaves a biological imprint is only the first step—the real power lies in what we do with this knowledge. If a father’s experiences can echo into the future, then so can his choices. This study is not meant to instill fear but to inspire action. It reinforces a truth we often overlook: the way we navigate our struggles today has the potential to shape the well-being of tomorrow.

Healing isn’t just about undoing the past; it’s about actively creating a new future. This means prioritizing mental health in ways that go beyond fleeting self-care trends. It means acknowledging emotional wounds, seeking therapy when needed, building supportive relationships, and practicing habits that reduce stress—because science now confirms that these choices have profound effects, not just mentally and emotionally but at the deepest molecular level.

It also means shifting societal expectations. For too long, men have been conditioned to suppress stress, to tough it out, to wear emotional struggles as invisible armor. But silence doesn’t erase stress—it buries it, only for it to resurface in ways we may not even realize. By fostering conversations about mental health and encouraging open emotional expression, we create an environment where future fathers can be healthier—both for themselves and for the generations that follow.

The message is clear: We are not just inheritors of the past; we are architects of the future. The cycles we continue or break today will shape the lives of those who come after us. And in that truth lies a profound responsibility—one that challenges us not just to live, but to heal with intention.

A Call to Awareness and Action

The past may have written the first draft, but the final story is in our hands. This study on stress and sperm doesn’t just reveal a biological mechanism—it serves as a wake-up call. It reminds us that our experiences, struggles, and emotions don’t simply vanish into the past. They become a part of us, woven into our very cells, with the potential to shape the next generation. But knowledge is power, and with this awareness comes the opportunity to change course.

Stress may leave a mark, but it does not define our future. We have the power to break cycles of inherited trauma, to shift patterns not just in our own lives but in those who come after us. Healing isn’t just a personal journey—it’s a legacy we create. By prioritizing mental health, by addressing past wounds, by choosing mindfulness, therapy, and emotional resilience, we are not just improving our own well-being; we are rewriting the biological script for future generations.

So, what story do you want to pass down? This research challenges us to be intentional, to recognize that every act of self-care, every effort to heal, is more than just for ourselves. It is for the children yet to be born, the families yet to be built, the generations yet to come. And that is the ultimate power we hold—the power to transform not just our own lives, but the future itself.

Featured Image Source: Shutterstock

Sources:

- Tuulari, J. J., Bourgery, M., Iversen, J., Koefoed, T. G., Ahonen, A., Ahmedani, A., Kataja, E., Karlsson, L., Barrès, R., Karlsson, H., & Kotaja, N. (2025). Exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with specific epigenetic patterns in sperm. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02872-3

- Tuulari, J. J., Bourgery, M., Iversen, J., Koefoed, T. G., Ahonen, A., Ahmedani, A., Kataja, E., Karlsson, L., Barrès, R., Karlsson, H., & Kotaja, N. (2025). Exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with specific epigenetic patterns in sperm. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02872-3

Loading...