Inside the Mind of a Girl Who Can Time Travel Through Memory

What were you wearing exactly ten years ago today?

For most people, the question triggers a blur. We might recall the school we attended, the city we lived in, perhaps even a friend we used to see every day. But the precise details usually dissolve under scrutiny. The color of the sky, the smell in the air, the exact words spoken at breakfast are gone. Memory, for the average person, is selective and fragile.

For a 17-year-old girl in France known publicly only as TL, that blur does not exist. She can close her eyes and return to almost any day of her life with remarkable clarity. She can walk through her childhood like someone flipping through carefully labeled files. Researchers studying her describe her ability as a rare case of hyperthymesia, also called highly superior autobiographical memory. In practical terms, it means she can mentally travel through time.

Her story has captured the attention of neuroscientists and the public alike. It sounds almost fictional, yet it opens serious scientific questions about how memory works, why we forget, and what might happen if we did not.

A Memory That Refuses to Fade

Hypermnesia, or hyperthymesia when it concerns autobiographical memory, is exceptionally rare. Fewer than a few hundred documented cases exist worldwide. People with this condition can recall personal experiences with extraordinary detail and accuracy, often anchored to specific dates. Ask them what happened on a random day years ago, and they may recount not only the event itself but also what they wore, how they felt, and even what the weather was like.

Scientists distinguish between different types of memory. Declarative memory includes facts and personal experiences. Within it lies episodic memory, the ability to relive events situated in time and space. Non declarative memory involves skills such as riding a bicycle or typing on a keyboard. Individuals with hyperthymesia typically excel in episodic memory, not necessarily in general intelligence or factual knowledge.

What sets TL apart is not simply that she remembers. It is how she remembers. Her recollections come with what researchers call autonoetic awareness, a vivid sense of mentally stepping back into the original moment. She does not simply know that something happened. She experiences it again.

Researchers at the Paris Brain Institute and Université Paris Cité conducted detailed assessments of TL’s memory using standardized tools designed to measure autobiographical recall. On tasks that asked her to retrieve childhood and adolescent memories, she scored well above average. Her accounts were highly specific and rich with sensory detail. She could shift perspective, describing events from her own point of view and then as if she were observing herself from the outside.

Yet even these formal tests only hinted at the complexity of her internal world.

Inside the White Room

TL describes her mind as organized into rooms. At the center is what she calls a white room, a large rectangular mental space with a low ceiling. This room functions as a personal archive of her life.

Within this imagined space, her memories are arranged thematically. There are sections for family life, school experiences, vacations, and friendships. Even her childhood stuffed animals have designated spots. Each toy carries what she calls a memory tag, which includes the date she received it and the person who gave it to her.

When she wants to recall something, she mentally walks into this white room and navigates to the appropriate area. The memory surfaces with sensory precision. She might remember the texture of a dress she wore on her first day of school, the pattern of sunlight on the ground, and the expression on her mother’s face as she watched from behind a fence.

This organization appears spontaneous rather than deliberately constructed. Unlike a mnemonic technique that someone might practice to improve recall, TL’s system feels natural to her. It is how her mind has always worked.

Interestingly, she distinguishes this vivid autobiographical space from what she calls black memory. Black memory contains semantic and academic knowledge. Facts learned in school, mathematical formulas, historical dates, and vocabulary words reside there. These memories lack emotional charge and are not spatially organized. They require effort to retrieve, much like they do for most people.

The contrast highlights an important scientific insight. Hyperthymesia does not grant universal memory superiority. It appears to amplify personal episodic memory rather than all forms of cognition.

Emotional Rooms and the Architecture of Feeling

TL’s inner world extends beyond storage. She describes additional rooms tied to emotional regulation.

One is a pack ice room, a cold mental environment she enters when she feels anger. Sitting there in her imagination helps cool her emotions. Another is a problems room, an empty space where she paces and reflects when facing difficulties. There is also a military room, associated with her father’s absence during military service, which evokes guilt and discomfort.

Even painful memories have designated places. In her white room, a chest contains memories of her grandfather’s death. They are not erased or softened. They remain vivid, sealed but accessible.

For researchers, this mental architecture suggests that memory and emotion are deeply intertwined. The way TL organizes her recollections may reflect not only how her brain stores information but also how she copes with its intensity.

This intensity can be both a gift and a burden. While many people gradually lose the sharp edges of painful experiences, TL can relive them with striking clarity. Experts note that individuals with hyperthymesia often recall negative events just as powerfully as positive ones. Insults, disappointments, and moments of grief may return with the same emotional force they carried originally.

In this sense, forgetting serves a protective function for most people. The human brain typically prunes unused connections, allowing certain details to fade. Without that process, emotional life could become overwhelming.

Traveling Into the Future

What makes TL’s case even more compelling is her ability to imagine future events with unusual richness.

During testing, researchers asked her not only to recall past experiences but also to construct hypothetical future scenarios. Her imagined events were detailed, plausible, and grounded in time and space. She described where they would occur, who would be present, and how she expected to feel.

More strikingly, she reported a sense of pre experiencing these events, a feeling akin to remembering something that has not yet happened. Scientists refer to this capacity as mental time travel. The same cognitive mechanisms that allow us to revisit the past may also enable us to simulate possible futures.

In the general population, imagined events tend to become less vivid the further they are projected into the future. TL showed a similar pattern, with slightly reduced detail for distant scenarios. Still, her ability remained exceptional compared to typical participants.

This connection between memory and imagination offers valuable clues. It suggests that when we envision the future, we draw upon fragments of past experiences, recombining them into new possibilities. TL’s enhanced autobiographical memory may provide a richer database from which to build these simulations.

The Science Behind Remembering and Forgetting

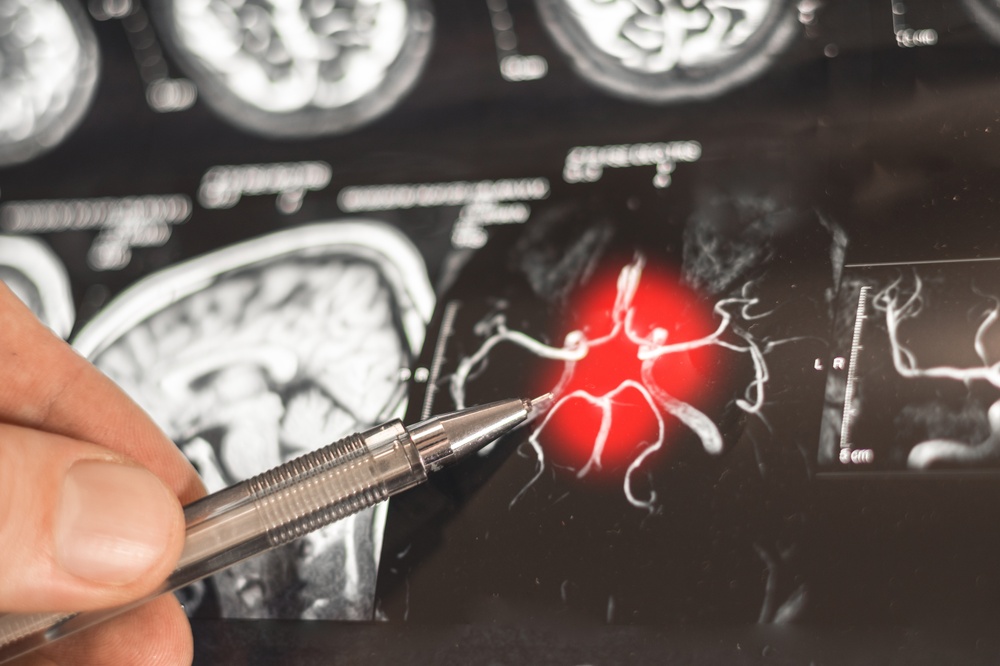

Understanding TL’s abilities requires a closer look at how memory works in the brain.

The hippocampus plays a central role in forming new memories and consolidating them into long term storage. Over time, many neural connections weaken if they are not revisited. This process of forgetting is not a flaw. It is an adaptive feature that helps prioritize relevant information.

Researchers speculate that in individuals with hyperthymesia, certain mechanisms of consolidation and retrieval operate differently. Their brains may reinforce autobiographical details more robustly or access them more efficiently.

However, studying such a rare condition presents challenges. TL’s case is based on a single individual. While she performed exceptionally on standardized autobiographical memory tasks, broader diagnostic tools such as extensive calendar verification were not fully applied. Childhood memories are also difficult to independently confirm, as they can be influenced by photographs, family stories, or dreams.

These limitations do not diminish the scientific value of the case. Rare profiles often serve as windows into normal cognitive processes. By examining extremes, researchers can refine theories about how memory, identity, and imagination interact.

A Life Lived in High Definition

Beyond laboratory measures, TL’s experience invites deeper reflection about what it means to remember.

For many of us, memory is stitched together from fragments. We rely on photographs to reconstruct childhood vacations. We debate with siblings about what really happened at family gatherings. Our sense of self evolves partly because details blur, allowing reinterpretation.

TL lives with a continuous thread of recollection. Her past is not distant terrain. It is a landscape she can reenter almost at will. This continuity may strengthen her sense of identity, as autobiographical memory plays a crucial role in shaping who we believe ourselves to be.

At the same time, the inability to fully escape painful moments could complicate emotional growth. Psychological resilience often depends on recontextualizing experiences, softening their impact over time. When every detail remains sharp, that process may require additional effort.

Researchers emphasize that hyperthymesia does not equate to photographic memory or universal genius. It is a specific amplification of personal episodic recall. Yet its implications stretch far beyond trivia about past dates.

Questions That Remain

TL’s case leaves scientists with numerous open questions.

Does hyperthymesia change with age? Will her abilities remain stable, intensify, or diminish over decades? Can individuals like TL learn to control the flow of memories more deliberately? Are there structural differences in their brains that imaging studies might reveal?

There is also the question of prevalence. With only around a hundred documented cases worldwide, hyperthymesia remains poorly understood. It is possible that more individuals possess similar abilities but have not come forward or been formally assessed.

Another intriguing avenue involves emotional regulation. TL’s internal rooms suggest that some people may develop mental architectures to manage overwhelming recollection. Could therapeutic techniques draw inspiration from such strategies, helping others cope with traumatic memories by visualizing containment or separation?

Each rare case contributes a piece to the broader puzzle of human cognition. As researchers continue to explore TL’s mind, they hope to illuminate not only extraordinary memory but also the everyday processes that shape how we all remember and forget.

What Her Story Teaches Us

It is tempting to romanticize the idea of perfect memory. To remember every joyful moment in vivid detail sounds like a gift. Yet TL’s experience reminds us that memory is deeply intertwined with emotion. To preserve everything is to carry everything.

For most people, forgetting allows space for healing and adaptation. It enables us to prioritize, to move forward, and to reinterpret our narratives. The selective nature of memory may be one of the brain’s quiet safeguards.

TL’s extraordinary capacity challenges our assumptions about the limits of the human mind. She demonstrates that mental time travel is not science fiction but a cognitive process rooted in the structures of memory and imagination.

Her story also highlights the importance of scientific curiosity. By documenting rare cases with care and humility, researchers expand our understanding of what it means to be human. They remind us that identity is not fixed but constructed through remembered experiences.

In the end, TL’s ability to walk through her white room and revisit the past invites a simple yet profound question. If we could remember every day with perfect clarity, would we truly want to?

For now, her mind remains both a marvel and a mystery. As science continues to explore the boundaries of memory, her story stands as a vivid example of the extraordinary potential within the human brain.

Loading...