When Fear Becomes Fact How Misinformation About Autism Turned Science Into a Story of Belief

Have you noticed how quickly we react to headlines but rarely pause to ask what lives behind them? One statement, one rumor, one press conference, and suddenly the world splits between belief and doubt. Especially when the topic touches what we hold most sacred, the health of our children.

The conversation around autism has once again been swept into that storm. Claims rise, studies get twisted, and emotion drowns out evidence. This is no longer just a question of science. It is about trust, fear, and how easily truth can fade when noise becomes the loudest voice in the room.

The Claim That Shook a Conversation

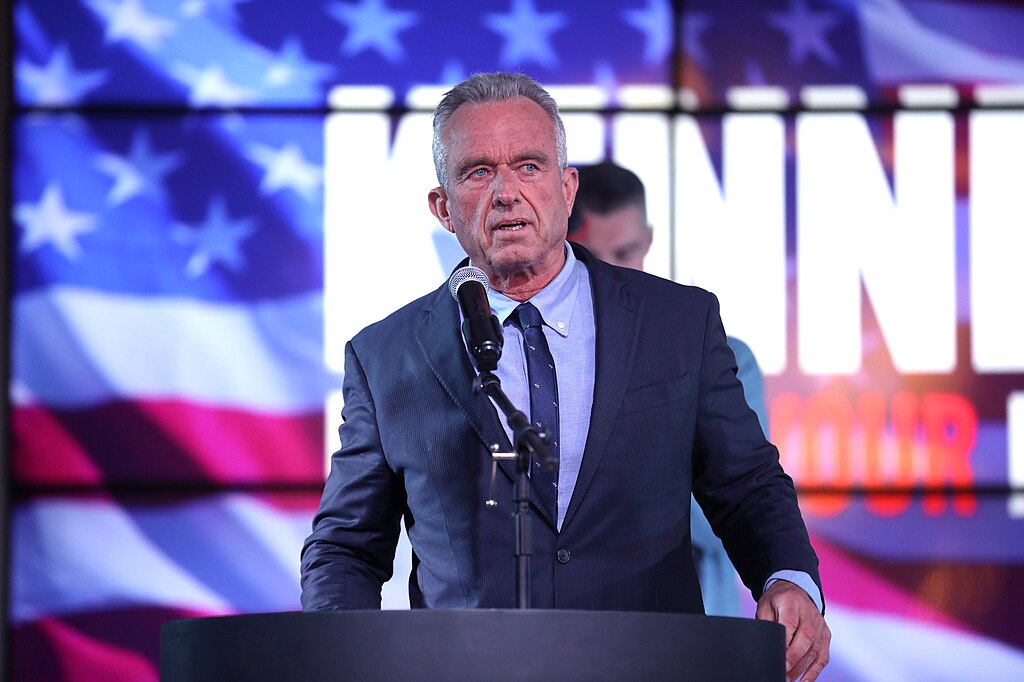

It started as another meeting in Washington, but it did not end that way. When Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the U.S. Health Secretary, spoke about autism, the room shifted. “There’s two studies which show children who are circumcised early have double the rate of autism. It’s highly likely, because they were given [acetaminophen] (Tylenol),” he said. Those words did not stay within the walls of the Cabinet room; they spread fast across headlines and feeds, fueling confusion and disbelief in equal measure.

Kennedy’s statement came just weeks after he and former President Donald Trump claimed that pregnant women who take Tylenol increase the chances of autism in their children. Scientists had already dismissed that theory, pointing out the lack of evidence connecting the two. Yet Kennedy doubled down, extending his argument to circumcision, suggesting that the painkillers given to newborns could be responsible for higher autism rates. He went so far as to call parents who use pain relief “irresponsible,” adding that his administration was “doing the studies to make the proof.”

It did not take long for experts to respond. Autism advocacy groups and public health organizations condemned the statement, describing it as “dangerous, anti-science, and irresponsible.” The National Autistic Society warned that such words could undo years of work in raising awareness based on real evidence. Medical experts clarified that no credible study has found a direct link between acetaminophen use, either during pregnancy or after medical procedures, and autism.

Some observers pointed to a 2015 study from Denmark, which found a correlation between circumcision and autism diagnoses. However, the research did not explore the use of painkillers or any mechanism that could explain causation. The authors themselves cautioned against overinterpreting the data. Critics later identified flaws in its design, reminding the public that correlation alone cannot prove cause.

Still, Kennedy’s claim found a willing audience in an age where information moves faster than verification. Social media turned it into a spectacle, with opinions flying before facts could find footing. It was another reminder that in the battle between science and speculation, truth often struggles to keep pace with the noise.

When Numbers Tell Half the Story

Science has always been a mirror. It reflects what we choose to ask and sometimes what we want to believe. When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. referenced studies to back his claim about circumcision and autism, that mirror became fogged with misinterpretation. He pointed to two pieces of research, one from 2013 and another from Denmark in 2015, as proof that early circumcision doubles the rate of autism in boys. Yet beneath the surface, the data told a much more complicated story.

The Danish study followed more than three hundred thousand boys and observed that those circumcised before the age of five seemed to have higher autism rates early in life. But the pattern faded as the children grew older. The authors themselves cautioned that the research could only show a connection, not prove one. They had no records of painkiller use, no evidence that acetaminophen played any part, and no way to separate coincidence from cause. Without those missing pieces, any conclusion about circumcision or medication influencing autism remained speculation rather than science.

Experts who reviewed the findings were quick to point this out. They explained that autism diagnoses depend on far more than medical procedures. Cultural traditions, healthcare access, and social awareness all shape when and how children are identified as being on the spectrum. Dr. Céline Gounder noted that circumcision is deeply connected to religion and culture, both of which influence patterns of diagnosis and treatment. Scientific American described the original research as “truly appalling,” not because of its subject but because of how easily weak data could be used to stoke fear. The broader scientific community agrees that autism cannot be traced to a single medical act or a common painkiller. The link Kennedy suggested does not stand on scientific ground but on selective interpretation that overlooks the depth and complexity of human biology.

The Psychology of Belief and Why False Ideas Stick

We often think misinformation spreads because people do not know enough, but that is not the full story. Most of us do not believe things because they are true; we believe them because they feel true. A statement that triggers fear or outrage can travel faster through our minds than a fact that demands patience. When a public figure speaks with confidence, emotion takes the wheel before reason can fasten its seatbelt.

The link between belief and emotion explains why health myths endure even when science disproves them. Humans crave certainty, especially when the subject involves children and health. The unknown is uncomfortable, so we fill it with stories that give us control. A claim like “painkillers cause autism” simplifies a complex disorder into something that feels solvable. It offers a culprit we can see, touch, and avoid. But comfort does not equal truth. The danger lies not only in what is said but in how easily it satisfies our need for clarity.

Breaking that cycle requires humility, not just education. We need the willingness to question what aligns too neatly with our fears. Scientists can provide evidence, but belief changes only when curiosity replaces defensiveness. The next time a bold claim grabs your attention, pause before sharing it. Ask not just “Is this true?” but “Why do I want this to be true?” That question, more than any statistic, can protect us from the quiet pull of misinformation.

The Human Cost of Misleading Health Claims

Every false claim about health leaves a mark that statistics cannot measure. When a public figure suggests that a simple painkiller or a common medical procedure could cause autism, the damage goes beyond confusion. It plants seeds of guilt in parents who have done nothing wrong. It fuels arguments at kitchen tables and in online spaces where fear replaces compassion. These moments fracture trust not only between people and science but between families and themselves.

Behind every headline are real parents who start to second-guess their choices. Some stop using medications that could ease a child’s fever. Others begin to fear routine medical care, believing they have harmed their children by following professional advice. This quiet erosion of trust becomes more dangerous than any one statement because it spreads invisibly through the lives of people who simply want to protect their families.

When misinformation takes hold, doctors become adversaries and research becomes suspect. The space between patient and professional fills with doubt, and in that space, real health progress slows down. Rebuilding trust requires empathy and transparency, not judgment. Science can correct falsehoods, but only compassion can heal the emotional wounds they leave behind. The truth is not just a set of facts; it is a relationship we must nurture through honesty, humility, and understanding.

The Quiet Work of Truth

Truth does not need to raise its voice to be heard. It waits patiently behind the noise, steady and unchanged, while the world rushes to react. In a time when opinions travel faster than facts, choosing to seek truth is not an easy path. It requires stillness, curiosity, and the courage to admit when we do not know enough.

The debate surrounding autism, painkillers, and medical claims shows how easily confusion can take root when fear becomes our teacher. Real science is not glamorous. It takes time, repetition, and humility. It does not offer instant answers but strives for accuracy, step by step. When we allow space for that process, we honor both the scientists who dedicate their lives to finding real solutions and the families who depend on their work.

Our collective challenge is to value truth more than comfort. Every time we pause before sharing a claim, every time we choose to verify rather than assume, we strengthen the fabric of understanding. Truth survives when people protect it with awareness and compassion. It does not need to fight to be believed; it only needs us to listen.

Loading...