Archaeologists Unseal a 40,000-Year-Old Cave to Reveal the World’s Last Neanderthals

It is easy to believe that we already know the full story of human origins, categorizing the past as simple and primitive. But a massive discovery on the coast of Gibraltar has just cracked open a vault that was sealed shut for forty thousand years.

What researchers found inside this untouched time capsule is not just a collection of old bones; it is a piece of evidence that forces us to completely rethink the timeline of intelligence and survival.

The Neanderthals of Gorham’s Cave

Time is often viewed as a fleeting river, but sometimes, it stands still. On the southern tip of Spain, in the shadow of the Rock of Gibraltar, lies a secret that remained hidden for millennia. For forty thousand years, a specific chamber within the Vanguard Cave system sat in total darkness, sealed off from the world by a thick wall of sediment.

In 2021, archaeologists broke through this barrier and stepped into a space that had not seen a living soul since the Ice Age. This was not merely a geological formation; it was a pristine time capsule. The air itself felt ancient. Scattered across the ground were the remains of lynx, hyenas, and griffon vultures. Yet, amidst these animal bones lay undeniable proof of intelligent life. A large whelk shell, found far from the shoreline, sat as a silent testament to a being that intentionally carried it there.

This excavation at the Gorham’s Cave complex offers a rare, intimate glimpse into the lives of our closest evolutionary cousins, the Neanderthals. Long dismissed by history as primitive brutes, the evidence preserved in these seaside caverns suggests a different story. They lived here, sheltered here, and survived here. As Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum, noted regarding the discoveries in this region, such finds bring the Neanderthals closer to us. It forces you to look at the ground beneath your feet and question the distance between the past and the present.

An Ancient Urge to Create

We carve initials into trees or doodle in the margins of notebooks just to say, “I was here.” It turns out this impulse is not unique to modern history. Deep inside Gorham’s Cave, under the light of a fire, a Neanderthal took a stone tool and etched a precise geometric grid into the bedrock.

For a long time, skeptics dismissed this as nothing more than a prehistoric cutting board. They claimed the lines were accidental scratches left behind from butchering meat. But science has dismantled that assumption. Researchers tried to replicate the marks by cutting pork skin on similar rocks and found that slicing meat leaves messy, chaotic grooves. You cannot control the tool when you are focused on the food.

The carving in Gibraltar was different. It was disciplined and deliberate. To create this simple “hashtag” design, the artist had to make between 188 and 317 calculated strokes. The rock was so hard that completing the design in one sitting would have likely caused physical pain to the carver’s hand. This was not a mindless chore. It was a dedicated project.

Francesco d’Errico, a leading researcher in the field, points out that this level of effort proves intent. Whether this was a map, a clan symbol, or a piece of art, it represents a massive leap in cognitive evolution. It shows a mind capable of abstract thought. This individual was not just surviving the night. They were expressing an idea.

Shattering the Myth of the Brute

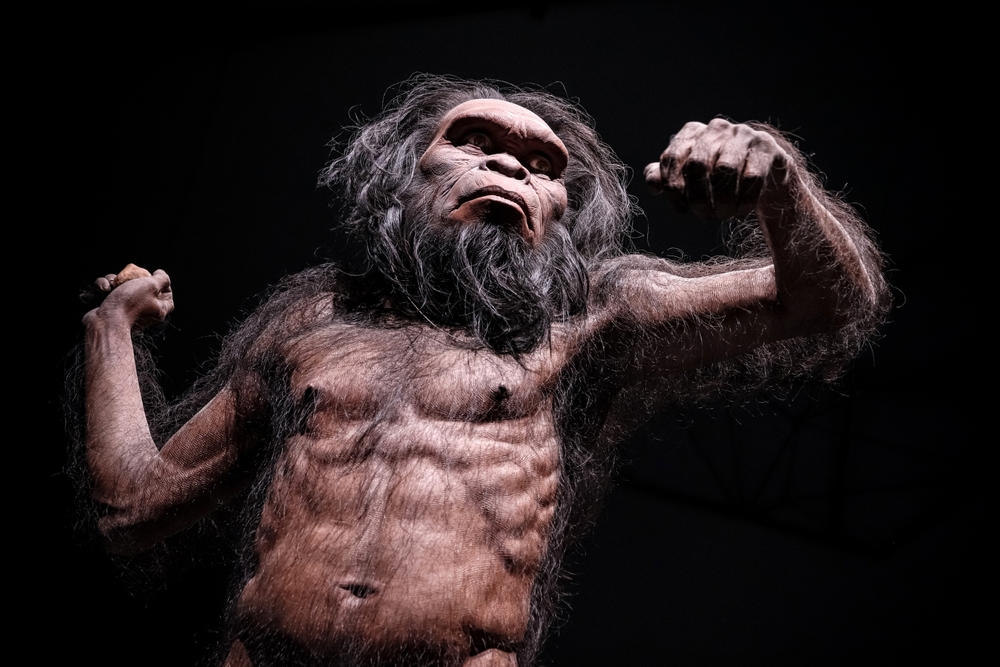

History has often painted a specific picture of the Neanderthal. We tend to imagine a knuckle-dragging brute, a creature lacking intelligence and focused solely on the raw basics of survival. The excavations in Gibraltar, however, shatter this stereotype. The evidence found within these caves reveals a species that was skilled, resourceful, and surprisingly sophisticated.

These ancient relatives were not merely scavenging for leftovers. They were masters of their environment. The cave floors are littered with the remains of roasted pigeons and vast quantities of seafood, including mussels, seals, and dolphins. Harvesting these resources requires an understanding of the tides and complex hunting strategies. They were adapting to the coast in ways that mirror modern human behavior.

Their intelligence extended into engineering. In Vanguard Cave, researchers discovered a 60,000-year-old hearth used to produce birch tar. This is a sticky, glue-like substance used to attach stone tips to wooden handles. Creating this tar requires precise temperature control and a complex heating process. It is a form of prehistoric chemistry that suggests knowledge was likely taught and handed down through generations.

Beyond their tools and diet, they showed signs of culture and self-awareness. Recent findings suggest they decorated their bodies with bird feathers and used red and black pigments as makeup or paint. They even buried their dead. These are not the actions of a mindless beast. They are the behaviors of a species capable of empathy, ritual, and a desire to be seen.

Rewriting History’s Timeline

We thought that the Neanderthals went extinct roughly 40,000 years ago. However, the soil layers in Gibraltar tell a radically different story. Radiocarbon dating from Gorham’s Cave suggests that Neanderthal populations occupied this site until between 33,000 and 24,000 years ago. This means they survived here thousands of years after they had vanished from the rest of the European continent.

The geography of the southern Iberian Peninsula created a unique “stronghold.” Clive Finlayson, the director of the Gibraltar Museum, notes that while modern humans (Homo sapiens) were spreading into other parts of Europe, they had not yet reached this southern tip. There is no archaeological evidence of modern humans in this specific area during that timeframe. Instead, the ground yielded Mousterian stone tools—a style exclusively linked to Neanderthals—buried in sediments that date far later than expected.

This changes our understanding of human evolution. It wasn’t a sudden, simultaneous global extinction. Instead, pockets of Neanderthal life persisted. In this specific region, they continued to butcher seals, maintain their tool-making traditions, and inhabit these coastal caves long into the period we associate with modern human dominance. The evidence confirms that this was not just a temporary stop; it was a long-term habitation that defied the timeline we once accepted as fact.

A Shared Heritage

History long labeled the Neanderthal as a primitive failure, a distinct contrast to the superior intellect of Homo sapiens. Yet, the precise carvings in the rock and the evidence of ritual care destroy that separation.

Think about the universal desire to be remembered. That simple grid etched into the cave floor is not just a series of lines. It is a shout across time. It reveals a being who felt the need to impose order on the chaos of nature and leave something behind. They solved complex problems, adorned themselves with beauty, and survived against the odds.

If a species once dismissed as unintelligent beasts actually possessed creativity and deep emotion, perhaps judgments made about others should be reconsidered. The gap between “us” and “them” is an illusion. Looking at that ancient mark reveals that the drive to create, to survive, and to matter is not a modern invention. It is a shared heritage. In the silence of that sealed chamber, the past offers a powerful lesson in humility. The reflection in the stone does not show a stranger. It shows a familiar soul.

Featured Image Source: Shutterstock

Loading...